Contents

- Author's Note: The Concept of Living Structure

- Preface: On Process

- Part 1. Structure-Preserving Transformations

- Interlude

-

Part Two: Living Process

- 6. Generated Structure

- 7. A Fundamental Differentiating Process

- 8. Step-by-step Adaptation: Gradual Progress Toward Living Structure

- 9. The Whole: Each Step is Always Helping to Enhance the Whole

- 10. Always Making Centers: So that every center is shaped by then next step in the differentiation

- 11. The Sequence of Unfolding: Generative sequences are the key to the success of living process whenever complex structure is being formed

- 12. Every Part Unique: Finely tuned to circumstance that every part becomes unique

- 13. Patterns: Generic Rules for Making Centers or "Making life enjoyable"

- 14. Deep Feeling: The aim of every living process is, at each step, to increase the deep feeling of the whole

- 15. Emergence of Formal Geometry: Appearance, finally, of coherent form

- 16. Form Language and Style: How can human beings implement a geometrical differentiating process successfully?

- 17. Simplicity

- Part Three: A New Paradigm for Process in Society - Evolution towards a society where living process is the norm

- Conclusion

Author's Note: The Concept of Living Structure

1권의 기본 아이디어는 이것입니다: 무기물과 마찬가지로 유기물에서도 살아있는 구조와 살아있지 않은 구조를 구분할 수 있다는 것입니다 The basic idea of Book 1 is this: Throughout the world, in the organic as in the inorganic, it is possible to make a distinction between living structure and non-living structure.

엄밀히 말하면 모든 구조물에는 어느 정도의 생명력이 있습니다. 1권의 주요 업적은 이러한 구분을 정확하게 하고, 다양한 구조에서 발생하는 생명의 정도를 관찰하고 측정할 수 있는 경험적 방법을 제공한 것입니다. 아마도 가장 중요한 것은 1권에서 살아있는 구조에 대한 부분적인 수학적 설명을 제공함으로써 살아있는 구조의 내용, 기능적, 기하학적 질서를 현실의 확립되고 객관적인 특징으로 볼 수 있도록 한 것입니다. Strictly speaking, every structure has some degree of life. The main accomplishment of Book 1 is in making this distinction precise, in providing empirical methods for observing and measuring degree of life as it occurs in different structures. Perhaps most important, I gave in Book 1 partly mathematical account of living structure, so that we may see the content of living structure, its functional and geometric order, as an established and objective feature of reality.

문제는 인간이 어떻게 살아있는 구조를 만들 수 있을까요? 어떤, 인간이-영감을-받은 과정을 통해 살아있는 구조를 만들 수 있을까요? The question is, How is living structure to be made by human being? What kind of human-inspired processes can create living structure?

Real life created by a process in the caribbean

It should be repeated again and again, and understood, that the capacity of a society to create living structure in its architecture is a dynamic capacity which depends on the nature and character of the processes used to create form, and to create the precise sequence and character of the unfoldings that occur during the daily creation of building form and landscape form and street form.

For this purpose I shall, in the chapters of this book, move from the technical language of structure-preserving process to the broader and more intuitive language of living process. I shall define a living process as any process that is capable of generating living structure.

Above all, the living processes which I shall describe, are - as it turns out - enormously complex. The idea that all living processes are structure-preserving turns out to be merely the tip of a very large iceberg of hidden complexity. The subject of living process is a topic of great richness, which is likely to keep us occupied for centuries as we try to master its variety of meanings and its attributes and potentialities.

Preface: On Process

1. A Dynamic view of order

1권에서는 건물, 식물, 그림, 우리 자신의 얼굴과 손 등 우리 주변의 세계를 체계적으로 배열된 센터들이 있고 전체 안에서 상호 작용하는 필드와 같은 구조로 보도록 초대합니다. 구조가 살아 있을 때 우리는 그것에 반응하여 우리 자신의 살아 있는 메아리를 느낄 것입니다. Book 1 invited us to see the world around us - buildings, plants, a painting, our own faces and hands - as field-like structures with centers arranged in a systematic fashion and interacting within the whole. When a structure is living we will feel the echo of our own aliveness in response to it.

2권에서는 시간이 지남에 따라 살아있는 구조가 어떻게 생성되는지 그 과정을 알아보는 다음 단계로 넘어갑니다; Book 2 takes the necessary next step of investigating the process of how living structure creates itself over time;

아이는 독창성과 완전성을 잃지 않고 어른이 됩니다 A child becomes an adult without ever losing uniqueness or completeness

도토리는 시작점과 끝점이 근본적으로 다르지만 참나무로 부드럽게 변신합니다. An acorn transforms smoothly into an oak, although the start and endpoint are radically different.

좋은 건물이나 도시는 살아있는 구조를 생성하는 살아있는 프로세스에 따라 펼쳐집니다. A good building or city will unfold according to the living process that generate living structure.

2권에서는 프로세스의 역할과 중요성, 그리고 프로세스가 살아 있는지 아닌지에 대해 생각해 보도록 초대합니다. 질서에는 본질적으로 동적인 것이 있기 때문에 순전히 정적인 용어만으로는 질서를 충분히 이해할 수 없다는 사실에 관한 것입니다. 살아있는 구조는 동적인 이해를 통해서만 실제로 달성 될 수 있으며 완전히 이해하고 도달 할 수 있습니다. 실제로 질서의 본질은 그 근본적인 성격이 질서를 만들어내는 과정의 본질과 맞물려 있습니다. Book 2 invites us to consider the role and importance of process and how it is living or not. It is about the fact that that order cannot be understood sufficiently well in purely static terms because there is something essentially dynamic about order. Living structure can be attained in practice, and will become fully comprehensible and reachable, only from a dynamic understanding. Indeed the nature of order is interwoven in its fundamental character with the nature of the process which create the order.

질서를 동적으로 바라볼 때, 살아있는 구조라는 개념 자체가 변화를 겪습니다. 1권에서는 살아있는 구조라는 개념에 초점을 맞추었고, 기하학적이고 정적인 관점이었습니다. 2권에서는 펼쳐진 구조라는 개념에 기반한 두 번째 개념으로 시작합니다. 구조 자체에 대한 관점도 동적입니다. When we look at order dynamically, the concept of living structure itself undergoes some change. Book 1 focused on the idea of living structure, and the viewpoint was geometric, static. In Book 2, I start with a second concept, based on the idea of an unfolded structure. The point of view -- even for the structure itself -- is dynamic.

구조의 두 가지 개념은 상호 보완적인 것으로 밝혀졌습니다. 결국 우리는 살아있는 구조와 펼쳐진 구조가 동등하다는 것을 알게 될 것입니다. 모든 살아있는 구조는 펼쳐져 있고 펼쳐진 구조는 모두 살아 있습니다. 그리고 저는 펼쳐진 구조의 개념이 *살아있는* 구조의 개념만큼이나 중요하고, 건축에서 필수적인 역할을 해야 한다고 믿습니다. 따라서 우리는 동일한 아이디어에 대해 정적, 동적이라는 두 가지 동등한 관점을 갖게 될 것입니다. The two conceptions of structure turns out to be complementary. In the end we shall see that living structure and unfolded structure are equivalent. All living structure is unfolded and all unfolded structure is living. And I believe the concept of an unfolded structure is as important, and should play as essential a role in architecture, as the concept of *living* structure. Thus we shall end up with two equivalent views -- one static, one dynamic -- of the same idea.

2. The necessary role of process

살아있는 건축물을 만드는 부품을 미묘하고 아름답게 조정할 수 있는 프로세스는 무엇일까요? 어떤 의미에서 답은 간단합니다. 건물 안에 있는 만 개의 살아있는 센터들을 하나씩 하나씩 만들어내거나 생성해야 합니다. 이것이 핵심적인 사실입니다. 그리고 만 개의 센터들이 살아있는 센터들이 되려면 전체 내에서 서로 아름답게 적응해야 합니다. 각 센터는 다른 센터들에 적합해야 하고, 각 센터는 다른 센터들에 기여해야 하며, 만 개의 센터들이 진정으로 살아있는 것이라면 일관되고 조화로운 전체를 형성해야 합니다. What process can accomplish the subtle and beautiful adaptation of the parts that will create a living architecture? In a certain sense, the answer is simple. We have to make -- or generate -- the ten thousand living centers in the bulding, one by one. That is the core fact. And the ten thousand centers, to be living centers, must be beautifully adapted to one another within the whole: each must fit the others, each must contribute to the others, and the ten thousand centers then -- if they are truly living -- must form a coherent and harmonious whole.

일반적으로 이 모든 것을 잘 수행하는 것이 건축가의 적절한 업무라고 생각합니다. 이것이 건축가가 해야 할 일입니다. 건축가는 이런 일을 하도록 훈련받았습니다. 그리고 이론적으로는 건축가가 할 줄 아는 일입니다. 건축가와 다른 사람들이 어떻게 하는지는 예술의 신비의 일부라는 일반적인 믿음이 있으며, 이에 대해 너무 많은 질문을 하지 않습니다. It is generally assumed that doing all this well is the proper work of an architect. This is what an architect is supposed to do. It is what an architect is trained to do. And -- in theory -- it is what an architect knows how to do. There is a general belief that how it is done by the architect and others is part of the mystery of the art; one does not ask too many questions about it.

따라서 우리는 건축가의 능력이나 훈련보다 (설계와 시공의) 프로세스가 더 중요하고 건물의 품질에 미치는 영향이 더 크다는 것을 알게 될 것입니다. 프로세스는 설계보다 건물의 생사를 결정하는 데 더 근본적인 역할을 합니다. Thus we shall see that processes (both of design and of construction) are more important, and larger in their effect on the quality of buildings, than the ability or training of the architet. Process play a more fundamental role in determining the life or death of the building than does the "design."

3. Order as Becoming

The waves of the ocean are the flowing product of the process of interaction between wind and water. ... In each case, the whole system of order we observe is only an instantaneous cross section, in time, of a continuous and ongoing process of flux and change.

일리아 프리고진이 여기서 나와? 자기조직화 참고.

4. Process, The Key to Making Life in Things

"Yes, this daily ordinary things is almost more important than the other."

But it is the two together: the daily pleasure, breathing in the smell of newly cut grass, with the deeper knowledge that goes with it that in this process he is making a living structure, up ther on the ridge of the Berkeley hills.

Once we recognize the possibility that some centers will be helpful to the life of an existing wholeness, while others will be antagonistic to it, we then begin to recognize the possibility of a highly complex kind of self-consistency in any given wholeness.

What is fascinating, then is the hint of a conception of value which emerges dynamically from respect for existing structure. We do not need any arbitrary or external criterion of value. The value exists within the unfolding of the wholeness itself. ... When the wholeness unfolds naturally, value is created.

That is the origin of living structure.

The further I went to understand the actual process which had been used to make the tile, the more I realized that it was this process, more than anything, which governs the beauty of the design. Perhaps nine-tenths of its character, its beauty, comes simply from the process that the maker followed. ... The design is indeed beautiful, yes. But it can only be made as beautiful as it is within the technique, or process, used to make it. And once one uses this technique, the design -- what appears as the sophisticated beauty of the design -- follows almost without thinking, just as a result of following the process.

The "design" of this beautiful work is not more than a tenth of what gives it its life. Nine-tenths comes from the process.

This gradual rubbing together of phenomena to get the right result, the slow process of getting things right, is almost unknown to us today.

5. Our Mechanized Process

반면 오늘날은, ...

They have been designed and constructed with no knowledge of the building at all; they are mentally and factually separate from its existence, but are brought into play only by a process of assembly.

The trouble is that it is mechanical process only, something which subverts the inner fire of true living process.

In a mechanistic view of the world, we see all things, even if for convenience, as machines. A machine is intended to accomplish something. It is, in its essence, goal-oriented.

For in fact, everything is constantly changing, growing, evolving.

Why is this process-view essential? Because the ideals of "design", the corporate broadroom drawing of the imaginary future, the developer's slick watercolor perspective of the future end-state, control our conception of what must be done - yet they bear no relation to the actual nature, or problems, or possibilities, of a living environment.

6. Possibility of a New View of Architectural Process

I shall argue that every good process in architecture, and in city planning also, treats the world as a whole and allows every action, every process, to appear as an unfolding of that whole. When living structure is created, what is to be built is made consistent with the whole, it comes from the whole, it nourishes and protects the whole.

We may get some inkling of this kind of thing by considering what it means to design a building, and to compare it with what it means to make a building.

More deeply, what it means for me to make a building is that I am totally responsible for it.

This is in marked contrast with the present idea of architecture, where as an architect I am desinitely not responsible for everything. I am only responsible for my particular part in the process, for my set of drawings, which will then function, within the system, in a strictly limited fashion that is shut off from the whole. I have limited responsibility.

When I make something, on the other hand, I am deeply involved with it and responsible for it. And not only I. ... In a good process, each person working on the building is -- and feels -- responsible for everything.

I shall prove that a process which is not based on making in a holistic sense, cannot create a living structure.

However, since the distinction between living process and non-living process has now become visible, and since, for the time being, we have no precise conception or definition of living process, it has become urgent that we try to get one.

.

Wholeness, defined structurally, is the inter-locking, nested, overlapping system of centers that exists in every part of space.

Part 1. Structure-Preserving Transformations

In the first four chapters I focus on the idea that a living process always has enormous respect for the state (and morphology and form) of what exists, and always finds a next step forward which preserves the structure of what exists, and develops and extends its latent structure as it creates change, or evolution, or development. This is the process which is "creative."

In chapters 1 and 2, I address these issues for cases in the natural world, and provide the outline of a tentative approach that helps us understand the unfolding of geometry in biology and physics. This theory provides the underpinning for what follows. In chapters 3 and 4, I turn my attention to the BUILT world, to towns and buildings and to the way the emergence of living structure in towns and buildings may be understoode within that context of theory.

1. The Principle of Unfolding Wholeness in Nature

1. Introduction

How does nature create living structure?

It is, in a more general sense, the character of all that we perceive as "nature". The living structure is the general morphological character which natural phenomena have in common.

What I call the living structure of nature is also largely governed by these fifteen properties and their interaction and superposition.

But why does living structure, with its multiplicity of centers and their associated fifteen properties, keep making its appearance in the natural world? Why and how, does living structure keep recurring in these widely different domains? What is the mechanics of the process by which living structure is made to appear, so easily, in nature? What is the process by which this kind of structure repeatedly, and persistently, occurs?

I start by trying to understand nature in a new way. Once we have that understanding, we may have a basis for thinking about architectural process and for creating a living world in the realm of architecture. In a good building, as in nature, there is also living structure. Each living center contains thousands of living centers; and the centers support each other in an intricate pattern.

"To learn how to create living structure in buildings, we had better start by looking at nature."

Note for the Scientific Reader

2. Structure-Preserving Transformations

1. Structure-Preserving Transformations

1장에서, 나는 모든 natural process가 어떻게든 "smooth"하다는 것을 소개했다.

process가 "smooth"하다는 것은 무슨 의미인가? 나는 smooth transformation을, preserve structure and wholeness한 transformation이라고 정의한다. 앞으로 이런 유형의 transformation을 structure-preserving transformation이라고 하겠다.

as a result of the repeated application of structure-preserving transformation to the wholeness which exists.

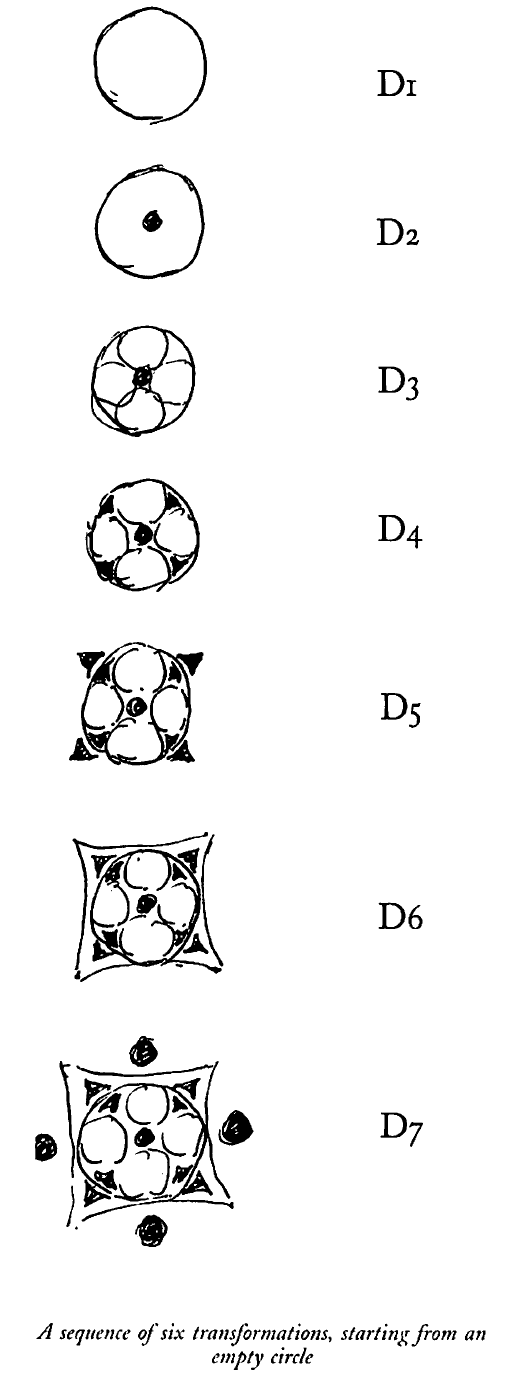

이 장의 스케치를 봐라.

매 단계마다, 추가(addition)나 주입(injection)이 있다. 어떠한 새로운 center가 도입된다. 하지만 이 새 센터는 foreign body처럼 무작위로 추가되지 않는다. It grows out of what was there before.

나는 존재하는 센터를 강화한다. 비록 그것이 처음에는 숨겨져 있고 약할지라도. 이 센터를 강화함으로써, 나는 센터들의 시스템 가운데 새로운 균형(balance)을 만들어낸다. 그리고 indeed disk를 통틀어 a modified system of centers를 야기한다. wholness가 변화했다. 센터들의 상대적인 강도가 변했기 때문이다. 그 센터들은 대단히 변하지 않았고, 살짝 변했다. 하지만 이 약간의 변화가 전체 구성의 wholeness를 바꾸었고, 그것은 우리가 강화를 했기 때문이고, 새로운 구조는 more highly differentiated than before has been created. 이것이 내가 구조-보존 변화라고 부르는 것이다.

D1->D2로의 변화를 살펴보자.

- 이 구조-보존 변화는 유일하지는 않다. 다른, 존재하며 숨겨져 있는 센터들이 강화되기 위해 선택될 수도 있었다. 하지만 그 선택지가 무한히 많지는 않다. 몇 개 되지 않는다.

- 새 구조는 이전의 텅 빈 원보다 조금 더 생명이 있다. 대단하지는 않지만, 조금, 하지만 알아챌 정도로.

- D2는, D1의 wholeness를 취하고, 그것을 강화하여 도달했다. 다른 말로, it arises from the structure as a whole, not from a fragmented portion of the structure. And it arises from a process that enhances and embellishes that whole.

- 이 rudimentary transformation에서도, 새로운 전체(whole)로서, D2가, emerge했고, 몇몇 15가지 속성들은 벌써부터 조금 강하게 나타나기 시작했다. 가운데 작은 원은 CONTRAST를 가지고 있고, GOOD SHAPE을 가지고 있고, 그것의 크기는 선택되었기 때문에, 그 주위의 빈 ring 공간은 BOUNDARY를 형성하는 등이다.

- 완전히 새로운 것은 어떤 것도 주입(injected)되지 않았다는 것에 주목하라. 새로움은 이미 존재하던 것을 강화하여 창조되었다. 그래서 그 과정(procedure)은 보존적(conservative. 기존에 존재하던 구조를 존중하기 때문에)이기도 하고 혁신적(innovative. 새로운 구조를 만들어냈고, 그것은 D1의 older structure에서는 보이지 않던 것이다)이기도 하다.

D2->D3, D3->D4, D4->D5, D5->D6, D6->D7 각각의 변화는 동일하게 동작했다. 앞의 다섯 가지 포인트는 매 단계에서 모두 일어났다.

2. Structure-Preserving Transformations Further Discussion

3. Structure-Preserving Transformations in Traditional Society

4. Structure-Destroying Transformations in Modern Society

Interlude

5. Living Process in the Modern Era: Twentieth-Century Cases Where Living Process Did Occur

Part Two: Living Process

6. Generated Structure

7. A Fundamental Differentiating Process

8. Step-by-step Adaptation: Gradual Progress Toward Living Structure

1. Introduction

모든 living process의 가장 기본적이면서도 필수적인 특징(feature)은 점진적(gradualy)이라는 것일 것이다.

살아있는 구조는 천천히, 한 발짝 한 발짝씩 emerge한다. 그리고 프로세스가 한 발짝씩 진행되는 동안, 지속적인 피드백(continuous feedback)이 있어서, 프로세스가 시스템을 더 큰(greater) 전체성(wholeness), 응집성(coherence), 적응(adaptation)으로 이끌게 한다. 생물학자나 생태학자에게는 이것이 self-evident하다.

현대 건축은 이와는 반대이다. process of design도, process of construction도 이렇게 작동하지 않는다. 그 대신에,

- conception of a desired end-state (the design)이 있고,

- the system of architetural and constructional process가 작동해서 그 desired end-state를 효율적으로 '생산(producing)'한다.

- 그 과정에서, 처음에 정의했던 비용들을 모두 들여서 진행한다. 프로세스가 진행되는 동안 realistic feedback이나 improvement, adaptation은 없다. 구조를 변경하는 것은 거대한 변환을 필요로 한다.

어떤 경우에도, the core of all living process는, step-by-step adaptation이다 - the modification and evolution which happen gradually in response to information about the extent to which an emerging structure supports and embellishes the whole. It is a necessary, unavoidable core.

(어떤 면에서는, 고대의 건축들은 기술의 한계 등으로 인해서 매우 천천히, 그리고 여러 시대에 걸쳐서 점진적으로 이루어졌을테고, 그게 living structure를 담지하게 되는데 도움이 되지는 않았을까?)

2. Back to Generated Structure Once Again

living process에 대한 most fundamental thing은, the geometry of living structure는 markedly different in kind from the geometry of design done on a drawing board or on the drafting system of a computer.

수선화를 만든다고 생각해보자. 수선화에 있는 수십억개의 원자들을 미리 설계한 청사진에 따라서 원자 핀셋으로 하나하나 배열해서 수선화를 만들 수 있을까? 그렇게 만들어진 꽃은 죽어있을까 살아있을까?

짧게 말해서, 우리가 살아있는 수선화를 만들려면, 단순하게 구근을 심고, 그것을 자라게 할 것이다. 우리는 직관적으로, 그 growth process가 바로 수선화의 비밀이라는 것을 안다. 살아있는 꽃은 comes from the fact that it has unfolded, step by step.

(살아있는) 건물 만들기도 크게 다르지 않다. 그 경우에도, must be allowed to unfold. 그것은, 수선화와 같이, it must take form step by step, in real time, both before construction and during construction. living structure의 geometry는 정적인(static) 설계나 생산에 의해 만들어지지 않는다. 수선화에서와 같이, it can be created only by the unfolding process itself. ... it really must unfold, in real time.

물방울이 떨어지는 모양. 이것도 어떤 정적인 그림이나 설계로는 그 모양을 만들 수 없고, 공중에서 물방울이 떨어지면서 물리법칙과 끊임없이 영향을 주고받으며 변화하면서 만들어진다.

그 모양은 컴퓨터 시뮬레이션으로 만들어질 수도 있다. 왜냐면 시뮬레이션은, 최소한 원칙적으로는, may resemble the real process by creating a succession of adaptations that build up the shape gradually. 하지만 it cannot be created by a static, non-dynamic act of draftmanship or design. ... 그것의 shape은 동적(dynamically)으로만 만들어질 수 있다. The shape of the water drop has living structure, as defined by 1권에서의 criteria. It is also, from what I have just described, a generated structure, arrived at by unfolding.

우리 시대에 그러한 프로세스의 현대 버전을 가지려면, we must have a process in society that is capable of generating the form of building dynamically, step by step. This must be true both of the process of design and of the process of construction.

3. Getting Things Right

nessary process를 그려(visualize)보자. 문앞 계단을 제대로 만든다고 해보자. 되게 많은 것들이 고려되어야 한다. We may start to visualize the necessary process by considering what it means to build a front doorstep correctly. Suppose I want to make a front doorstep outside a house, and I want to make it just right.

예를 들어, 계단이 편안하게 걸을 수 있는 적당한 높이와 깊이인지 아닌지는 직접 밟아보지 않고는 알 수 없습니다. 하지만 시도해 보려면 걸을 수 있을 만큼 단단한 무언가가 있어야 합니다. (실제 조작할 수 있는 환경을 만들어서, 실험/시도를 해봐야 안다는 얘기) For example, I can't really tell if the step is just the right height and depth to walk onto comfortably without trying it out. But to try it out I must have something which is solid enough to walk on.

돌이나 벽돌, 블록을 이용해 어떤 것이 적당한지 스스로 알아낼 수 있습니다. 나무 덩어리로도 할 수 있고, 테스트할 수 있는 거의 모든 것을 사용하여 편안함을 확인할 수 있습니다. 그런 다음에야 계단을 만들 수 있습니다. 또는 계단을 '만드는 동안'에도 똑같이 할 수 있습니다. 예를 들어, 블록이나 벽돌을 깔고 확인한 다음 너무 낮은 것 같으면 위에 모르타르를 1인치 더 얹고, 너무 짧은 것 같으면 반 블록 깊이를 더 추가하여 조정할 수 있습니다. 어떤 경우에도 조화로운 무언가를 원한다면 실제로 계단을 만들고 구체적으로 구체화하는 과정과 그것을 파악하고 점차적으로 무엇을 해야 할지 알아내는 과정을 분리할 수 없습니다. (이런 저런 재료들을 가지고 만들어보고, 느낌을 보고, 편안한지 확인해보고.) I can get an idea of what feels right by using stones or bricks or blocks to help myself find out what seems to work. I can also do it with lumps of wood, with anything almost that gives me some opportunity to test it out, and check it for its comfort. Then I can build the step. Or I can do the same even while I am building the step: for instance, I can lay a course of block or brick, then check it, and then adjust it with an inch of mortar on top if it seems too low, or with an extra half-block of depth if it seems too short. At all events, if I want something harmonious, I cannot separate the process of actually building the step, and of having it materialize concretely, from the process of figuring it out and gradually finding out what to do.

이 프로세스들은 살아있는 센터들(living centers)의 탄생(creation)에 직접 맞닿아 있다. 문앞 계단을 만드는 동안, I am trying to make each part of it a living center. 예를 들자면, 그건 이런걸 의미한다. 맨 윗 계단을 a strongly felt center로 만들 수 있는 정확한 깊이와 너비를 찾고 싶다고 하자. 그러기 위해서는, 이 strong centeredness of the top step은 is created out of the wholeness of 그것을 둘러싼, 나는 반드시 문자적으로 "get" the step - 그것의 크기, 모양, 높이 - from the surroundings, and from the wholeness of the surroundings. These processes tie in directly with the creation of living centers. As I make the doorstep, I am trying to make each part of it a living center. That means, for instance, I want to find the exact depth and width which make the top a strongly felt center. To do it, since this strong centeredness of the top step is created out of the wholeness of what surrounds it, I must literally "get" the step - its size, shape, height - from the surroundings, and from the wholeness of the surroundings. The existence of the step as a center comes about as a function of the centers in the path, wall, garden, ground, and trees all around. It arises from the wholeness of these existing centers in such a subtle way that I could never hope to get it right merely by studying drawings of the surrounding centers, or from memory, or from any other indirect method. It is only when I am actually standing inside the wholeness of what exists that I can reliably create a step which will be a true living center inside this wholeness.

따라서 이 작은 사례 하나라도 살아 있는 센터를 만들려면 실제 장소에서 시도해야 하고, 시도하는 동안 생각해야 합니다. 이런 동적인 과정은 모든 살아 있는 센터들을 만들기 위해 반드시 진행되어야 하는 과정입니다. Thus to create a living center at all -- even in this one tiny case -- I must try to do it in the actual place, and be thinking while I do it. Such a dynamic process is a necessity which must be going on in order to make living centers at all.

따라서 완전히 적응된 세계를 얻으려면 동일한 원리를 백만 배나 큰 사물을 포함하여 모든 규모에 적용하도록 확장해야 합니다. So, to get a fully adapted world, the same principle has to be extended to cover all scales including even things which are a million times as big.

4. Step-By-Step Adaptation

수천 번의 적응을 수행해야 하는 적응 프로세스의 실제 난이도를 파악하려면 변수가 30개인 작은 시스템을 상상해 보세요. 각 변수의 상태를 동전으로 표현하고, 앞면이 앞면일 때는 성공적으로 적응하고 뒷면일 때는 적응에 실패했다고 가정해 보겠습니다. 제 목표는 서른 개의 동전을 모두 앞면이 위로 향하도록 테이블 위에 올려놓는 것입니다. 이제 이 목표를 달성하기 위한 두 가지 가능한 접근 방식을 고려해 보겠습니다: To grasp the real difficulty of an adaptive process in which thousands of adaptations have to occur, imagine a small system with thirty variables. Let us say that the state of each variable is represented by a coin, successfully adapted when it is heads, unsuccessfully adapted when it is tails. My goal is to get all thirty coins lying heads up on the table in front of me. Now, consider two possible approaches to achieving this goal:

- The All-Or-Nothing Approach

- The Step-By-Step Approach

단계별 접근 방식은 동작합니다. all-or-nothing 접근 방식은 동작하지 않습니다. 이것이 바로 생물학적 진화의 비밀입니다. 진화의 과정에서 하나의 성공적인 유기체를 만들기 위해 발생해야 하는 수천, 수백만 가지 변수의 적응은 본질적으로 한 번에 하나의 유전자씩 단계적으로 일어납니다. 이것이 바로 진화를 가능하게 하는 것입니다. 자연이 유기체처럼 복잡한 시스템을 한 번에 '설계'하는 것은 불가능합니다. The step-by-step approach works. The all-or-nothing approach does not work. This is the secret of biological evolution. During the course of evolution, the adaptation of the thousands and millions of variables that must occur to make one successful organism happens step by step, essentially one gene at a time. That is what makes evoluiton possible. It would be impossible for nature to "design" a system as complex as an organism all at once.

건물을 설계하고 건축할 때도 마찬가지입니다. 건물이 잘 적응하고 살아있는 구조를 갖추려면 말입니다. 건물에는 너무 많은 측면과 너무 많은 변수가 있습니다. 한 번에 한 가지 측면만 해결하지 않으면 건물의 각 측면을 제대로 구현할 수 없습니다. 30개의 동전이 모두 앞면이 되도록 하는 것이 바로 이러한 방식이지만, 건물에서는 설계와 시공 과정에서 '수천' 개의 변수를 하나씩 차례로 처리할 수 있어야 합니다. The same must happen when a building is designed and built, if it is to be well adapted and to have living structure. A building has too many aspects, too many variables. We cannot get each aspect of the building right unless it is possible to work out one aspect at a time. This is how we get the system of thirty coins to be all heads, except that in a building it it must e possible to do this for thousands of variables, one after the other, both during design and construction.

그렇다면 건축 환경이 올바르게 만들어지고, 사회에 적응하고, 건물과 거리를 올바르게 만들 수 있는 능력을 회복하기 위해서는 반드시 충족되어야 하는 간단한 조건이 있다고 추론할 수 있습니다. 프로세스는 모든 규모(at all scales)와 모든 레벨(at all levels)에서, 구조물 전체에서 발생하는 살아 있음의 정도(degree of life)에 대한 진단(assessments), 수정 및 개선이 이루어질 수 있는 방식으로 점진적으로 진행되어야 합니다. 이 프로세스는 구상, 설계 및 시공 전반에 걸쳐 지속적으로 이루어져야 합니다. 그리고 이 프로세스는 모든 규모의 건물과 건축에 영향을 미칠 수 있을 만큼 충분히 광범위하게 적용되어야 합니다. We may infer, then, that to make things come out right in the built environment, to bring adaptation into society and to regain our capacity to make buildings and streets just right - there is a simple condition that must be met. The process must go gradually, in a way that allows assessments, corrections, and improvements to be made about the degree of life which occurs throughout the structure, at all scales and at all levels. This process must occur continually throughout conception, design and construction. And the process must be sufficiently widespread to affect all scales of building and construction.

5. Feedback

물론 단계별로 진행하는 것만으로는 충분하지 않습니다. 단계별 적응의 일환으로 '피드백' 프로세스도 반드시 필요합니다. Of cource, it is not enough merely to go step by step. As part of the step-by-step adaptation, there must also be a feedback process.

따라서 잘 작동하려면, 살아있는 프로세스는 단순히 단계별로 이루어져서는 안됩니다. 한 걸음 한 걸음 나아갈 때마다 발생할 살아있음의 증가를 한 번 확인하고, 있으면 받아들이고, 없으면 거부할 수 있는 종류의 피드백이 '내장된(built-in)' 단계적이어야 합니다. So, to work well, a living process must not merely be step by step. It must be step by step with a built-in feedback of such a kind that each step taken can be checked at once for the increase of life which will occur, accepted if it has it, rejected if it does not.

설계를 할 때는 일반적으로 설계도부터 시작합니다. 이 도면은 복잡하기 때문에 보통 수천 개는 아니더라도 수백 개의 결정 사항이 포함되어 있습니다. 하지만 이러한 의사 결정을 서로 분리하면 그 중 어느 하나도 테스트되지 않은 채 종이 위에서 이루어집니다. 물론 어느 단계에서 도면이 고객에게 보여지고 고객은 완성된 전체에 대해 의견을 제시할 수 있는 권리가 있습니다. 하지만 그때가 되면 밑그림의 윤곽은 거의 정해져 있고, 아직 테스트되지 않은 수백 개의 의사 결정이 포함되어 있습니다. 이 디자인이 탄생하기까지의 백여 단계 중 어느 하나도 테스트되지 않은 경우가 많았고, 건축가인 우리도 단계별로 실제 피드백을 줄 수 있는 현대적인 디자인 방법을 사용할 수 없었습니다. During design, typically, we start with a schematic drawing. This drawing, being complex, usually contains hundreds (if not thousands) of decisions. Yet these decisions, if we separate them from one another, have been made on paper without one of them being tested. Of course, at some stage the drawing is shown to the client, and the client has the right to comment on a completed whole. But by that time, the drawing, in its outline, is all but set, containing hundreds of untested decisions. Often not one of the hundred steps which led to its creation has been tested, nor have we, the architects, had available to us a contemporary method of designing which can give us real feedback, step by step, as we work it out.

고객으로부터의 코멘트는 있습니다. 그도 또한 사무실 안에 있는 사람입니다. 하지만 제안된 건물의 실제 동작에 대한 진정한 피드백은 거의 없습니다. ... 그러나 설계된 대로 현재 구성이 실제로 설계자가 원하고 믿고 있는 기능적 특징을 가지고 있는지 경험적으로 테스트되었습니까? There are comments from the client, from others in the office, and so forth. But little true feedback about the actual behavior of the proposed building. ... But have they been tested empirically to see if the current configuration, as designed, actually has these functional features that are wanted and believed in by the designer?

(3d modeling을 한다고 할 때) 이러한 디자인 프로세스가 피드백을 통해 단계적으로 진행되기 위해서는 다음과 같은 일이 일어나야 합니다: 지속적으로, 설계를 진행하면서 완성된 홀의 실제 경험에 충분히 근접한 3차원 형태로 홀을 모델링해야 하며, 이 모델을 통해 분위기, 느낌, 음향 등에 대해 현실적인 판단을 내릴 수 있고, 진행하면서 3차원 형태의 개선을 할 수 있어야 합니다. In order to make such a design process go step by step with feedback, the following thing would have to happen: continuously, while making the design, we would have to model the hall in a three-dimensional form sufficiently close to a person's real experience of the finished hall, so that this model would enable us to make realistic judgments about atmosphere, feeling, acoustics, etc., and would help us to make improvements in the three-dimensional form as we go along.

그러나 복잡한 건물 공간이 그 안에 있는 사람들에게 미치는 효과는 더 복잡하며, 현재로서는 정량화할 수도 없고 컴퓨터 시뮬레이션의 3차원 이미지와 슈퍼그래픽을 통해 확실하게 경험할 수도 없습니다. 따라서 아무리 컴퓨터 시뮬레이션을 해도 우리가 알고 싶은 것, 즉 "어떤 느낌이고, 우리에게 어떤 영향을 미치는가?"에 대한 답을 얻을 수 없습니다 이런 종류의 피드백이 없으면 건물의 느낌을 강화할 수 없기 때문에 건물을 크게 개선할 수 없습니다. 그렇기 때문에 현대적인 방법으로 건물 디자인을 만드는 것이 우리에게 깊은 영향을 미치는 경우는 거의 없습니다. But the effect of a complex building space on the people in it is more complex; it is not, at present, quantifiable, nor is it reliably experienced by means of three-dimensional images and supergraphics in computer simulations. As a result, no amount of computer simulation tells us what we want to know, which is, "How does it feel, what is its visceral effect on us?" In the absence of this kind of feedback, the building cannot be significantly improved because its feeling cannot be intensified. That is why the creation of a building design, by contemporary means, only very rarely succeeds in having a profound effect on us.

이 문제에 대한 실용적인 해결책이 있습니다. 도움이 되는 한 가지 접근 방식은 간단하고 저렴하며 빠르게 테스트, 수정, 테스트, 수정, 수정을 거듭하여 좋은 솔루션이 발전할 수 있도록 하는 일련의 종이 및 판지 모형을 사용하는 것입니다. 아주 간단하고 의도적으로 거친 종이와 판지 모형이 효과적입니다. 찢고, 자르고, 테이프로 붙이고, 붙이고, 붙여나가면서 모델을 계속 개선해 나가면 됩니다. 너무 조잡해서 잘라도 상관없고 테이프, 스크랩, 조각, 조각이 전체의 효과를 방해하지 않을 정도로 거칠게 만든 모형이 있는 경우에만 이 작업을 수행할 수 있습니다. 오늘날 이러한 모델은 디자인 목적으로 거의 사용되지 않습니다. 모델은 프레젠테이션에 매우 자주 사용되지만 이는 디자인이나 피드백에 기여하지 않는 또 다른 문제입니다. There are practical solutions to this problem. One approach that helps is the use of a long series of simple, cheap, quick, paper and cardboard models which can be tested, modified, tested, modified, rapidly, one after the other, so that a good solution has a chance to evolve. Very simple, intentionally rough paper and cardboard models do work. You tear, cut, tape, patch, and paste as you go, making the model better all the time. You can only do this if you have a model so crude that you don't mind cutting into it, and so roughly made that tape, scraps, bits, and pieces do not distract from the effect of the whole. In today's practice, such models are rarely used for design purpose. Models are very often used for presentation, but this is quite another matter, one that does not contribute to design or feedback.

6. The Result Must Be Unpredictable

단계별 프로세스에서 피드백을 의미 있게 만들려면 프로세스의 끝이 열려있어야(open-ended) 하며, 따라서 부분적으로 예측할 수 없어야 합니다. 고정되고 미리 결정된 최종 상태가 없어야 합니다. 이는 적응 과정에 대응하여 변경할 수 없다면 적응 자체가 아무런 의미가 없기 때문에 필요합니다. 정의상 이러한 변화는 예측할 수 없습니다. To make the feedback meaningful in a step-by-step process, the process must be open-ended, hence partly unpredictable. It must lack a fixed, predetermined end-state. This is necessary because adaptation itself means nothing if changes cannot be made in response to the process of adaptation. By definition, such changes cannot be foreseen.

그러나 적응과 피드백이 작동할 때는 결과를 예측할 수 없어야 합니다. 최종 결과는 아직 알 수 없다는 암묵적인 인식이 있어야 합니다. But when adaptation and feedback are working, the result must be unpredictable. There must be tacit recognition that the end-result is not yet know.

이는 설계 과정에서 건물 프로젝트의 최종 결과를 예측할 수 없어야 한다는 의미뿐만이 아닙니다. 당연한 말입니다. 하지만 살아있는 구조를 효과적으로 만들기 위해서는 시공 과정에서도 예측할 수 없어야 합니다. This means not only that the end-result of a building project ust be unpredictable during design. That is obvious. But to be effective in creating living structure, it cannot help also being unpredictable during construction.

집의 창문을 생각해 보세요. 방을 건강하게 만들려면 창문은 방에 좋은 빛을 만들어야 하고, 근거리 및 원거리 전망과도 좋은 연결을 만들어야 합니다. 하지만 "좋은" 연결이란 무엇일까요? 그것은 실제 상황의 중요한 사소한 부분에 달려 있습니다. 집의 틀을 짜고 있는데 새로 나온 방 중 하나에 서 있으면 외부의 실제 풍경이 어디를 바라보게 만드는지 정확히 알 수 있습니다. 하지만 그 순간 바깥 풍경이 나에게 말을 건네는 정확한 방식은 매우 미묘합니다. 나무의 단풍, 하늘의 밝기, 외부에서 들려오는 소리, 멀리 보이는 산봉우리의 유무에 따라 달라질 수 있습니다. Consider the windows in a house. In order to make rooms wholesome, the windows must create good light in the rooms, and must also create a good connection with near and distant views. But what is a "good" connection? It depends on important minutiae of the real situation. If a house is being framed, and I stand in one of the emerging rooms, I will see exactly where the actual landscape outside makes me inclined to look. But the precise way that the landscape outside speaks to me, at that moment, is very subtle indeed. It may depend on the foliage on the trees, on the brightness of the sky, on the sound which comes from the outside, on the presence or absence of a distant mountain peak.

이런 종류의 판단은 '현실 세계에서만 잘 할 수 있'습니다. 아무리 세심한 건축 도면이라도 이런 미묘한 차이를 반영할 수는 없습니다. 판단을 내리는 데 필요한 정보에는 건물 계획을 세울 당시에는 존재하지도 않는 기초, 벽, 건물 질량의 전체가 포함됩니다. 이러한 판단을 정확하게 하려면 실제 건물이, 그것이 진행중일 때, 필요합니다. This kind of judgement can only be made well in the real world. No detailed architectural drawing, no matter how careful, can reflect this kind of subtlety. The information needed to make the judgement includes the wholeness of the foundations, walls, building mass - which do not even exist at the time the building plans are made. You need the real building, in its emergent state, to make this judgement accurately.

발생학 이론의 최근 발전, 특히 소위 나비 효과는 다양한 맥락에서 제가 여기서 말하는 내용을 뒷받침합니다. 나비 효과의 핵심은 다음과 같습니다: 복잡한 자연계가 진화하는 과정을 살펴보면, 진화의 다음 단계는 이전 단계에 따라 달라집니다. 19세기 기계론적 과학은 이전 단계로부터 다음 단계를 쉽게 예측할 수 있는 사고 모델을 만들었습니다. 하지만 세상은 기계적인 사고 모델과 다르다는 것이 밝혀졌습니다. 보다 정교한 발견을 통해 복잡한 시스템에서 다음 단계는 전체의 현재 구성에 따라 달라지며, 이는 다시 이전 전체의 역사에서 미묘한 세부 사항에 따라 달라질 수 있기 때문에 새로운 시스템의 경로를 미리 정확하게 예측할 수 없는 "흔적과 같은" 상태라는 것이 분명해졌습니다. Recent advances in the theory of morphogenesis, especially the so-called buterfly effect, support what I am saying here, in a wide variety of contexts. The essential point of but butterfly effect is something like this: If we examine a complex natural system evolving, each next stage of its evolution depends on its previous stage. Mechanistic 19th-centry science created a thought-model in which the next stage would be easily predictable from the previous stage. But it turns out that the world is not like the mechanical thought-model. More sophisticated discoveries have made it clear that in a complex system the next stage is dependent on the current configuration of the whole, which in turn may depend on subtle minutiae in the history of the previous wholes, so "trace-like" that there is no way to predict the path of the emerging system accurately ahead of time.

이 새로운 유형의 이론의 핵심은 작은 차이에서 최종 결과의 매우 큰 차이로 이어지는 다양한 진화 경로가 바로 제가 주장하는 살아있는 구조를 짓는 일에서 일어나야 한다고 주장하는 것과 정확히 일치합니다. 건물을 짓는 동안 창을 정확하게 인식(그리고 처리)하면 처음에는 사소한 차이로 이어질 수 있지만 몇 단계만 거치면 완전히 다른 큰 구성으로 이어질 수 있습니다. 이런 의미에서 하나의 작은 세부 사항이라도 상황과 가장 조화를 이루는 필요한 전체를 완전히 바꿀 수 있으며, 이러한 차이는 전체가 펼쳐질 때만 역동적으로 볼 수 있습니다. The key point of this new type of theory - divergent evolutionary paths leading from tiny differences to very large differences of end result - is exactly the one which I argue must occur in building living structure. Accurate perception (and treatment) of a window during the construction of a building may lead, at first, to minor differences but, within a few steps, to entirely different larger configurations. In this sense, even one small detail can completely change the necessary whole which is most in harmony with the situation, and this difference can only be seen dynamically as the whole unfolds.

또한, 창을 달리하면 다음 단계에서는 더 큰 차이가 발생합니다. 어떤 창문은 집 내부에 문을 한 방향으로 배치해야 할 수도 있고, 다른 창문은 내부 칸막이를 이동하고 문을 완전히 없애는 계획이 필요할 수도 있습니다. 그리고 세 번째 단계(실제 시공까지는 아직 몇 주밖에 남지 않았습니다.)에서는 건물 내부의 전개 방식에 따라 사람들의 동선 구성, 정원, 건물 전체 영역의 인공 채광에 영향을 미칠 수 있습니다. 따라서 살아있는 구조의 핵심인 센터 분야는 본질적으로 매우 미묘하여 동적으로만 생성될 수 있으며, 최종 상태에 대한 정확한 정의가 본질적으로 예측할 수 없습니다. What is more, the window which is different then leads to an even larger difference at the next step. One window may require a door inside the house to be placed one way; another may require a plan which moves the internal partition and does away with the door altogether. And then, at a third stage - still only a few weeks away in real construction time - this divergence in the unfolding of the building interior could have results for the organization of people's movement through the building, or for gardens, or for artificial light throughout an entire region of the building. Thus the field of centers which is at the very heart of living structure - is inherently so subtle that it can only be created dynamically, and is inherently unpredictable in the precise definition of its end-state.

7. Unfolding of a Painting by Matisse

저는 독자들에게 현대의 맥락에서 단계별 적응이 무엇을 의미하는지에 대한 그래픽 이미지를 남기고 싶습니다. 마티스의 그림 한 점의 진화 과정에서 일어난 단계별 적응을 보여줌으로써 이 작업을 수행하겠습니다. 다음 장에서 다룰 내용을 미리 맛볼 수 있습니다. I should like to leave the reader with a graphic image of what step-by-step adaptation means in the context of our modern era. I will do this by showing step-by-step adaptation as it occurred in the evolution of one painting by Matisse. It gives a foretaste of what is coming in the following chapters.

약 10분 동안 그가 작업하는 모습을 보여주는 이 단편 영화에서 가장 흥미로운 점은 그의 손과 붓이 춤추는 듯한 느낌을 준다는 점입니다. 손은 캔버스 위에서 떨리면서 맴돌고 있습니다. 때때로 손이 아래로 내려가 캔버스에 닿기도 합니다. 그런 다음 손이 다시 위로 올라가 그림 위를 맴돌며 진동하고 춤을 춥니다. 그는 그림에서 가장 시급하게 다음 중심이 필요한 부분을 찾고 있는 것 같습니다. 그런 다음 몇 초 더 떨리는 동작을 한 후 다시 그 부분을 찾고 손이 내려가고 붓이 그림에 닿아 또 다른 중심이 형성됩니다. 그런 다음 손이 다시 일어나고 떨리는 진동 동작이 다시 한 번 시작되고 다시 한 번 아래로 내려가 다음 중심을 형성하는 표시를 만듭니다. 그의 손은 기이할 정도로 확실합니다. 그는 보고, 듣고, 보고, 찾은 다음 곧바로 손이 내려가서 표시를 합니다. 몇 번이고 반복해도 그 과정은 동일합니다. What is fascinating about the short film, which shows him working for about ten minutes, is the dance-like quality of his hand and his brush. The hand hovers, quivering, above the canvas. Every now and then, it dips down, and he touches the canvas. Then the hand goes up again, and hovers, oscillating, dancing, above the painting. He seems to be looking for that part of the painting which most urgently needs the next center. Then, after a few more seconds of this quivering motion, he finds it again, the hand goes down, the brush touches the painting, and another center is formed. Then his hand rises again, and the quivering, oscillating motion starts once more, until once more, it dips down to make the mark which forms the next center. His hand is uncanny in its certainty. He looks, listens, watches, finds, then his hand goes straight down to make the mark. Again and again and again, the process is the same.

이 과정에서 가장 흥미롭고 아마도 가장 중요한 것은 그림의 '건축'이 펼쳐지는 것입니다. 이 여덟 장의 스틸에서 우리는 건축이 어떻게 펼쳐지는지, 그리고 놀랍게도 그 모습을 볼 수 있습니다. The most fascinating and perhaps most important thing about this process is the unfolding of the architecture of the painting. In these eight stills, we see how, and show suprisingly, the architecture unfolds.

그가 한 걸음 한 걸음 움직일 때마다 끊임없이 맴돌며 떨리는 손의 진동을 보여줄 수 있다면 좋겠습니다. 그가 생각할 때에도 그의 붓은 떨립니다. 그런 다음 한 발자국을 내딛기 위해 아래로 내려가 항상 떨고, 다시 후퇴하고, 다시 떨면서 더 생각합니다. I wish I could show the incessant hovering, trembling vibration of his hand, as he moves from step to step. Even when he is thinking, his brush quivers. Then it darts down to do a step, all the time quivering, then retreats, quivering again, while he thinks some more.

1단계에서는 POSITIVE-SPACE 변환으로 시작합니다. 반대쪽 페이지에서 볼 수 있듯이 여성의 머리 윤곽은 부분적으로만 존재하며, 이미 그려진 줄무늬의 포지티브 공간으로 둘러싸인 빈 캔버스로 형성되어 있습니다. 그것은 이미 놀랍습니다. 머리 자체에 너무 좁게 집중하는 사람이 할 수 있는 방식이 아니니까요. 그러나 이것은 살아있는 과정에 필요한 것이며 그림을 진정한 건축물에 맡기는 것입니다. 로마의 놀리 계획의 공간에서와 같이 공간에 대한 집중은 아름답고 질서 정연한 전체를 위한 길을 열어줍니다. In step 1, it starts with the POSITIVE-SPACE transformation. As shown on the opposite page, the outline of what is to be a woman's head is only partially present, formed as a void of blank canvas surrounded by the positive space of the stripes already painted in. That is already a surprise. It is not the way a person concentrating too narrowly on the head itself would go about it. Yet it is this which is needed by a living process, and this which commits the painting to a true architecture. Concentration on space, as in the spaces of the Nolli plan of Rome, paves the way for a beautiful and ordered whole.

마티스는 2단계로 넘어가면서 BOUNDARY를 형성합니다. 실제로 그는 얼굴을 어둡게 하여 나중에 머리카락이 있을 밝은 공간을 형성합니다. 다시 말하지만, 지배하는 것은 공간이며, 여자의 얼굴이 될 어두운 덩어리는 이 단계에서는 거의 이상하게 보이지만 빛의 경계, 즉 머리카락이 될 프레임에서 아키텍처를 형성합니다. As Matisse moves to step 2, he forms a BOUNDARY: actually, he darken the face, forming now a light space where later the hair will be. Again, it is the space which governs, and the dark mass which will be the woman's face looks almost strange at this stage, yet it forms an architecture in the frame of the light boundary, that is the hair-to-be.

3단계에서 마티스는 나중에 부풀어 올라 눈이 될 작은 어두운 선을 임시로 배치합니다. 이 선은 얼굴을 두 영역으로 나누고 주로 곡선형 눈썹의 형성을 지배하는 것은 GOOD-SHAPE의 변형입니다. In step 3, Matisse tentatively places small dark lines which will swell later to become the eyes: these lines divide the face into two zones, and it is the GOOD-SHAPE transformation that mainly governs the formation of the curved eyebrow.

4단계에서는 얼굴의 주요 선이 어둡게 터치되어 이제 확장된 구조를 형성합니다. 이 선들은 얼굴의 볼륨에 일관된 구조를 형성하기 때문에 여성을 연상시키지 않습니다. In step 4, we seethe main lines of the face, darkly touched in, forming now an extended architecture. These lines are not so much reminiscent of the woman as they form a coherent architecture in the volume of the face

5단계에서는 코와 눈을 더 강렬하게 그려서 내부 구조가 의미를 갖기 시작합니다. 갑자기 머리카락이 들어오고, 꿈틀거리는 컬 덩어리가 어둡고 확실하게 터치됩니다. In step 5, the nose and eye are more intensely drawn, so that their own internal architecture begins to means something. Suddenly, the hair comes in, a writhing mass of curls, darkly and definitively touched in.

6단계에서는 경계에서 더 많은 일이 일어났습니다. 이제 여성의 컬들로 센터들이 만들어졌습니다. 얼굴보다 어두운 이 어둠이 양과 음을 반전시키고 지금까지 머리카락의 공간이었던 밝은 경계 안에 이 컬의 구조를 배치하기 때문에 이것 역시 놀랍습니다. 여기서 컬이 의자의 줄무늬를 배경으로 어떻게 건축물을 형성하는지 볼 수 있습니다: 머리카락에서 말하는 빛은 그녀의 머리와 벽을 연결합니다. In step 6 more has happened in the boundary - now made of centers which are the woman's curls. This, too, is surprising, since this darkness, darker than the face, reverses the positive and negative, and places the architecture of these curls within the light boundary that was the space of the hair up until now. We see here how the curls form an architecture with the stripes of the chair behind: The light speaks in the hair connect her head to the wall.

7단계에서는 여성의 턱 아래에 선이 그려져 이제 머리가 몸과 가슴에서 선명하게 돋보이게 하고 가슴의 흰색 선도 부조로 배치하여 전체가 입체적으로 만듭니다. In step 7, a line is drawn under the woman's chin, now clearly making her head stand out from her body and her chest, placing also the white line of her breast in relief, making the whole three-dimensional.

8 단계에서는 얼굴 측면에 추가 컬과 컬을 추가하여 어깨 위로 랩핑하고 머리 구조를 완성합니다. In step 8, the side of her face gets additional curls and tresses, lapping over her shoulder and completing the structure of the head.

전체적으로 마티스의 떨리는 집중력, 즉 붓의 유희와 붓에 대한 피드백은 거의 춤을 추며 단계적으로 건축물을 형성합니다. 놀라운 것은 얼굴이 살아 있는 정도와 15개 변형을 통해 얼굴에 건축물이 형성되는 정도입니다. 고대 건축가들은 알고 있었지만 오늘날 사용되는 프로세스가 더 이상 살아있는 프로세스가 아니기 때문에 우리 중 너무 많은 사람들이 잊어 버린 아키텍처입니다. Throughout, the quivering, focused attention of Matisse's brush - the play of brush and feedback to the brush - nearly dances and forms the architecture, step by step. What is remarkable is the extent to which the visage lives, and the extent to which an architecture is formed in the face by means of the fifteen transformations. It is an architecture which ancient builders knew, but which too many of us have now forgotten - because the process used today is not a living process any more.

8. Architectural Implications

마티스의 성공적인 프로세스와 오늘날의 전문 건축에서 흔히 볼 수 있는 실패한 프로세스의 본질적인 차이점은 무엇일까요? 스키드모어, 오윙스 앤 메릴과 같은 대형 상업 사무소의 건축가가 자신의 설계를 그리면서 자신이 하고 있는 일이 마티스 프로세스와 똑같다고 주장한다고 가정해 봅시다. 대답할 수 있을까요? 한 프로세스와 다른 프로세스 사이에 객관적인 차이가 있을까요? What is the essential difference between Matisse's successful process and the unsuccessful process typical of our professional architecture today? Suppose an architect at a large commercial office like Skidmore, Owings & Merrill is drawing his design, and then makes the claim that what he is doing is just like the Matisse process. Can we answer? Is there an objective distinction between the one process and the other?

중요한 차이점은 피드백이 없다는 것입니다. 마티스의 프로세스에서 각 단계는 이전에 존재했던 현실에서 한 걸음씩 나아가는 과정입니다. 다음 단계는 실제 그림의 현실이 드러날 때 피드백을 받고 그에 대한 반응으로 이루어집니다. 이것이 작업을 계속 진행하게 하고 더 나은 결과물을 만들어내는 원동력입니다. 마티스가 실제 그림을 보고 있고 그의 손이 그림 위에 떠 있습니다. 그는 실물에 반응하여 색을 한 점 더 떨어뜨립니다. 마티스의 모든 움직임은 실물의 직접적인 피드백에 대한 반응이며, 진화하는 그림이 만들어내는 전체적 느낌에 대한 반응입니다. 따라서 이 과정은 실제 그림을 항상 더 좋게 만들 수 있는 좋은 기회를 제공합니다. The critical difference is the absence of feedback. In Matisse's process, each step is a small step forward from a previously existing reality. The next step is taken as feedback and as a response to the reality of the actual painting, as it emerges. That is what keeps the thing on track, and what keeps making it better. Matisse is watching the actual painting; his hand is hovering over it. He drops down one more spot of color, in response to the real thing. Each move he makes is response on the direct feedback from the real thing, and the real feeling as a whole, which the evolving painting creates. The process therefore has a good chance of making the real painting better all the time.

건축가가 테이블이나 컴퓨터에서 그림을 그리는 것은 완전히 다른 경우입니다. 건축가는 건물을 그리고 있습니다. 그러나 실제 건물이 형성되는 것이 아니며, 실제 건물이 궁극적으로 사용자의 마음속에 만들어낼 것과 같은 느낌과 감각을 만들어내는 데 근접할 수 있는 시뮬레이션도 아니기 때문에 건축가는 그림을 그리는 동안과 자신이 그린 것을 통해 실제 건물이 지어지면 실제 건물에서 실제로 어떤 일이 일어날지 알 수 없습니다. 종이 위에 그려진 선만으로는 실제 동작, 즉 실제 건물의 성격을 판단할 수 없기 때문에 그는 종이 위에 그려진 도면으로부터 현실적인 피드백을 받을 수 없습니다. The architect drawing at his table or on his computer is an entirely different case. The architect is drawing the building. But since it is not the real building which is being formed, nor any simulation which might come close to creating feelings and sensations like those which the real building will ultimately create in the user's mind, the architect cannot tell, while he is drawing and from what he draws, what would really be going on in the actual building if it were built. He gets no realistic feedback from the drawing on paper because one cannot judge the real behavior, the nature of the real building, by looking at the lines on paper.

그렇기 때문에 건축가가 연필 스케치로 하는 일은 마티스가 의자에 앉아있는 여인을 그릴 때했던 것과는 전혀 같지않습니다. 기껏해야 건축가는 무언가를 그리는 것이고, 다음 단계는 드로잉에 대한 반응입니다. 따라서 각 연필 스트로크는 이전 연필 스트로크 세트에 대한 반응 일뿐입니다. 어떤 단계에서도 현실에 대한 피드백에 기반한 것이 아니기 때문에 이 과정이 궤도를 벗어날 가능성은 항상 존재합니다. 현실에 대한 지속적인 대응이 부족하기 때문에 대기업에서 사용하는 프로세스는 매우 취약하며, 필연적으로 실패할 수밖에 없습니다. That is why what we architects do with our pencil sketches is not in the least like what Matisse did when he painted the Woman in a Chair. At best the architect is drawing something, and his next step is a reaction to the drwaing. Each pencil stroke is thus only a reaction to a previous set of pencil strokes. Since it is not, at any step, based on feedback about reality, there is every chance - one might say there is a certainty - that this process is going to go off the rails. It is the lack of continuous responses to reality which makes the process used by big commercial offices highly vulnerable, and which makes it - inevitably - unsuccessful.

이것이 바로 우리가 건축에서 열망해야 하는 아이디어입니다. 건물이든, 거리든, 방이든, 다리든, 구상, 설계, 시공, 그리고 궁극적으로는 유지보수까지 아주 작은 단계로 피드백을 받아 수정할 수 있는 세상을 상상해야 합니다. 최근 들어 거의 사라진 것이 바로 이러한 건축 과정의 자가 수정 측면입니다. That is the idea we must aspire to in architecture. We must imagine a world where, whether it is a building, or a street, or a room, or a bridge, the conception, design, and the construction - and ultimately the maintenance too - go forward in very small steps with feedback, so that they can be corrected. It is this self correcting aspect of the building process which has all but vanished in recent times.

살아있는 세상을 성공적으로 만들기 위해서는 모든 건축 과정을 실험적이고 반응적인 방식으로 진행할 수 있는 방법을 다시 찾아야 합니다. 모든 디자인, 모든 계획, 모든 건축의 기반이 되는 이 한 가지만으로도 세상은 바뀔 것입니다. 우리는 지금 미래를 계획하는 통계적 개념을 거부하고 각 건물의 미래를 알 수 없고 실험과 변화, 무엇보다도 성공에 열려 있는 새로운 건축 설계의 세계를 받아들여야 합니다. To create a living world, successfully, we must again find ways of making all building process move forward in this experimental, responsive fashion. That one thing alone, as a kind of bedrock for all design and all planning and all building, will change the world. We must reject the statist conception in which the future is planned now, and embrace a new world of architectural design in which the future of each building is not known, remains open to experiment and change, and above all to success.

9. Overall Implications

복잡한 건물, 마을, 거리를 만드는 것은 설계와 시공 모두에서 - 피드백을 통해 한 걸음 한 걸음 나아가고, 지속적으로 일을 올바르게 할 수있는 세심한 적응 과정을 거쳐야만 생명을 얻는 데 성공할 수 있다 - 는 사실이 여러분의 마음 속에 확립되기를 바랍니다. I hope I have established, in your mind, that creation of complex buildings, towns, streets - both in design and construction - will succeed in getting life only if it goes forward step by step, with feedback, in a minutely careful process of adaption which can, continuously, get things right.

이 결론이 디자인 분야와 건축 분야 모두에서 받아들여진다면 환경에 대한 사고의 분수령이 될 것입니다. 그것은 이 책이 담고 있는 모든 내용에 필수적인 토대를 마련하는데, 제 생각에는 피할 수 없는 조건이 무엇인지를 정의하기 때문에 모든 전개, 즉 세상의 생활 구조를 구축하는 모든 생활 과정에 필요합니다. This conclusion, if accepted both within the discipline of design and within the discipline of construction, must lead to a watershed in thinking about the environment. It lays a necessary foundation to all of what this book contains, since it defines what is, in my mind, an ineluctable condition, necessary to all unfolding, hence to all living process aimed at building living structure in the world.

이는 현재의 계획, 설계, 건설, 생산 방식에 거의 모든 면에서 심각한 결함이 있다는 것을 의미합니다. 단계별 적응을 포함하지 않고, 원칙적으로 이대로 유지하는 한 적응할 수 없기 때문에 이러한 생산 형태를 바꿔야 한다는 의미입니다. In substance, it implies that our present forms of planning, design, construction, and production are, nearly all, deeply flawed. Since they do not include step-by-step adaptation - and cannot in principle do so, so long as they stay as they are - it implies that these forms of production must be changed.

살아있는 프로세스가 필요하고 우리의 생산 수단을 완전히 바꿀 수 있다는 생각에 대한 인식은 이제 막 자리 잡기 시작한 것 같습니다. Awareness of the idea that living process is both necessary - and likely to change our means of production entirely - is perhaps only now beginning to sink in.

9. The Whole: Each Step is Always Helping to Enhance the Whole

1. Introduction

8장에서는 살아있는 과정에서 일어나는 모든 일은 단계적으로 진행된다고 말합니다. 그렇다면 단계별로 일어나는 일이란 정확히 무엇일까요? 이 질문에는 다른 무엇보다도 한 가지 답이 있습니다. 무엇보다도 각 단계가 전체를 향상시킨다는 사실이 있습니다. Chapter 8 say that in a living process everything that happens, goes step by step. Now, we may ask, What exactly is it that happens, step by step? The this question, there is one answer above all others. Above all, there is the fact that each step enhances the whole.

2. Common Sense

적어도 더 큰 전체에 생명을 불어넣는다는 목표는 이해되고 존중받을 것이라고 상상할 수 있습니다. 하지만 이마저도 항상 그렇지는 않다는 사실을 충격적으로 알게 되었습니다. 1988년 댄 솔로만과 저는 캘리포니아주 패서디나 시로부터 시 전역의 신축 아파트 설계를 안내하고 통제하는 새로운 구역 설정 조례를 작성하도록 임명받았습니다. 조례의 초기 초안에는 새 아파트 건설 프로젝트 신청자가 따라야 할 새로운 규칙의 주요 절차 중 하나로 다음과 같은 규정 초안을 포함시켰습니다: "제안된 모든 새 아파트 건물은 거리와 이웃의 삶에 실질적인 도움을 주어야 합니다."라고 명시했습니다. One would imagine that at least the goal of bringing life to larger wholes would be understood and respected. I discovered, with something of a shock, that even this is not always so. In 1988, Dan Soloman and I were appointed by the City of Pasadena, California, to write a new zoning ordinance guiding and controlling the design of new apartment building throughout the city. In an early draft of the ordinance, as one of the major processes in a new set of rules to be following by any applicant for a new apartment building project, I included a draft rule which stated: "Any proposed new apartment building must help the life of the street and of the neighborhood in some tangible way."

이것은 가장 명백한 상식입니다. 이 말을 듣는 비전문가라면 거의 모든 사람이 "음, 그래, 물론... 이게 뭐 새로운 거지? 당연히 해야 할 일이죠. 좋은 생각이네요."라는 반응을 보일 것입니다. This is the most obvious common sense. Almost any non-professional person who hears this, would have a reaction something like, "Well, yes, ... of course.... what is new about this? It is the obvious thing to do. A good idea."

하지만 패서디나에서는 그런 일이 일어나지 않았습니다. But that is not what happened in Pasadena.

이 이야기를 하는 이유는 부분적으로는 이 책의 독자들이 세계의 생활 구조에 관한 깊고 명백한 문제에 대해 공감하지 못할 수도 있다는 점을 미리 이해하고 대비하는 것이 중요하다고 생각하기 때문입니다. 구조를 보존하는 프로세스를 달성하는 것이 불가능하다는 의미는 아닙니다. 그것은 단지 많은 서클에서 사람들이하려는 일의 요점을 이해할 수 있도록 다소 신중하게 기반을 준비해야 할 수도 있음을 의미합니다. I tell this story partly because it is important, I think, for readers of this book to understand well in advance, to be prepared, perhaps, for a lack of sympathy even on such a deep and obvious matter concerning the living structure of the world. It does not mean that structure-preserving processes are impossible to achieve. It just means that in many circles, it may be necessary to prepare the ground rather carefully, so that people understand the point of what one is trying to do.

하지만 저는 이 이야기를 하는 또 다른 중요한 이유도 있습니다. 저는 우리 각자가 삶의 과정이라는 개념을 붙잡으려고 할 때 직면해야 하는 개별적인 어려움에 주목하고 싶습니다. 패서디나 기획위원회의 회장은 확실히 적대적이었습니다. 하지만 안타깝게도 우리 대부분, 때로는 우리 자신의 머릿속에도 이와 같은 부정적인 목소리가 자리 잡고 있어 모든 프로세스를 진정으로 더 큰 전체에 구조를 보존하지 못하도록 방해합니다. 이것은 일종의 정신적 억제(때로는 자아에 의해, 때로는 탐욕에 의해 촉진됨)로서, 우리가 지속적으로 국지적인 것에만 집중하게 만들고, 큰 틀에서 생명력 있고 아름다운 일을 만들어야 한다는 것을 잊거나 무시하게 만들며, 또는 매번 세상의 구조를 더 온전하게 만들어야 할 책임이 우리에게 있다는 것을 잊어버리게 만듭니다. But I also tell this story for another more important reason. I wish to draw attention to the individual diffifulty that each one of us must face when we try to keep hold of the conception of living process. The president ot the Pasadena Planning Commision was antagonistic, certainly. But unfortunately there is some negative voice like this sitting inside most of us, sometimes even inside our own heads, discouraging us from really and truly making every process structure-preserving to the larger whole. This is a kind of mental inhibition (sometimes fueled by ego, sometimes by greed) which continually makes us focus on the local, and forget, or ignore, the extent to which we must make something living or beautiful happen in the large - or forget that it is our responsibility, at every turn, to head and make more whole, the structure of the world.

3. The Whole

그렇다면 전체(whole)의 확장, 강화, 심화가 모든 살아있는 프로세스의 핵심이자 목표라고 말할 수 있습니다. 살아있는 과정은 전체의 창조와 관련이 있습니다. 예술적으로 건축가 예술의 본질은 항상 전체를 창조하는 것입니다. 건물이 성공하는 것은 우리가 그것을 인식하고 느끼기 때문이며, 전체를 관통하는 하나의 장엄한 전체로 인식하기 때문입니다. Let us say, then, that extension, enhancement, and deepening of the whole is the crux and target of all living process. Living processes have to do with the creation of wholes. Artistically, the essence of the builder's art, is always to create a whole. When a building succeeds, it is because we perceive it, feel it, to be a magnificent whole, whole through and through, one thine.

따라서 살아있는 과정이 건축에 대해 무엇을 말하든, 건축이 우리에게 무엇을 가르치든, 건축이 우리에게 무엇을 줄 수 있든, 무엇보다도 건축은 우리에게 이것을 제공해야 한다고 생각합니다: 살아있는 전체를 만드는 능력. Thus, whatever a living process has to say about architecture, whatever it can teach us, and whatever it can give us, above all it must give us this: the ability to make a living whole.

물론 이것은 문제가 있습니다. 이것은 수수께끼 같은 주제입니다. 예를 들어, 우리는 주변 환경과 하나가 되지 않으면 무언가 전체를 만들 수 없습니다. 따라서 전체가 되려면 주변 환경과 분리되어 있지 않아야 합니다. 즉, 주변 환경의 일부분과 일부가 분리되어 있지 않아야 합니다. 그리고 살아있는 전체 내의 조각들은 특별한 품질을 가져야합니다. 따라서 전체가 되어 주변 세계로 뻗어나가는 것은 그 '내부'에도 전체를 포함해야 하며, 이 작은 전체는 느낌상 더 큰 전체의 일부여야 합니다. 따라서 각각은 구별되어야 하고 하나의 실체가 되어야 합니다. 그러나 보이지 않아야 더 큰 전체에서 분리되지 않고 잃어버리지 않습니다. 건물을 전체적으로 만드는 것은 엄청나게 복잡한 작업입니다. 하지만 어쨌든 전체를 만드는 것은 예술가로서 우리 작업의 본질이자 시작이자 끝입니다. 그리고 (8장에 따르면) 이것은 단계별로 진행하면서 이루어져야 합니다. This is problematic, of course. It is an enigmatic subject. We cannot make something whole, for example, unless we make it united with its surroundings. So, to be whole, it has to be "lost", tat is, not separate from its surroundings, part and parcel of them. And the pieces within a living whole, they must also have a special quality. So, the thing which is to be whole, and extends out into the world around it, must also contain wholes within it, and these smaller wholes must be part of the larger whole in feeling. So each is to be distinct, to be an entity. Yet it is to be invisible in order to be lost and not separate from the larger whole. Making a building whole, is an immensely complicated task. But, in any case, making the whole is the essence, the beginning and the end of our work as artists. And (according to chapter 8) this is to be done while going step by step.

이제 살아있는 과정이 전체를 창조하는 데 어떻게 도움이 될 수 있는지 설명해 봅시다. 이 작업이 우리의 창의력에 부담을 줄 수 있지만 자연이 더 쉽게 관리한다는 사실을 상기하는 것이 도움이 될 수 있습니다. 산이 생태계의 풍경에서 솟아오를 때, 산은 하나의 전체가 됩니다. 이 모든 것은 구조를 보존하는 변형(structure-preserving transformation)을 통해 이루어집니다. 따라서 우리가 자연을 닮기를 바란다면(그리고 그보다 더 강한 것을 열망할 수는 없습니다) 원칙적으로 우리가 만드는 것에서 전체를 추출하고, 항상 단계별로 진행하며, 모든 단계에서 새롭고 살아 숨 쉬는 느낌과 전체의 출현에 집중함으로써 작업의 형태와 실체인 전체를 도출할 수 있어야 합니다. Let us then start articulating the way that a living process can help us to create a whole. It is possibly helpful to remind ourselves that although this task may tax our creative powers, nature managers it more easily. When a mountain rises up from the landscape over the econs, it becomes a whole. All this is arcieved, apparently, by structure-preserving transformations. So if we hope to be like nature (and we can hardly aspire to anything stronger) we should, in principle, be able to extract the whole in what we make, derive the whole - the shape and substance of our work - always going step by step, and by concentrating, at every stage, on the emergence of a new, living, breathing, feeling, whole.

4. To Be Guided by The Whold, We Must Pay Attention To The Latent Centers & Enhance Them

252페이지에 표시된 생 마르 광장의 진화를 생각해 보세요. 약 1000년에 걸친 이 과정은 항상 전체로서 진행되었고 사람들이 전체에 주의를 기울였기 때문에 가능했다고 말하고 싶습니다. 하지만 무슨 전체냐고 반문할 수도 있습니다 1000년이 지난 후 눈에 보이게 된 전체는 서기 560년경에 작업이 시작되었을 때는 분명히 보이지 않았고 심지어 생각할 수도 없었습니다. 그렇다면 정확히 어떤 어떤 전체가 작업을 이끌고, 작업을 앞으로 나아가게 하고, 더 큰 전체를 향해 다음 단계로 이끌었나요? Consider the evolution of St Mar's Square, shown on page 252. I would like to say that this process, lasting about 1000 years, achieved what it did because the work was always going forward as a whole, and people were paying attention to the whole. But, you may quite reasonably say, What whole? The whole which became visible at the end of 1000 years was plainly not visible or even thinkable when the work started around 560 A.D.. So what whole, exactly, was guiding the work, pulling the work forward, guiding the next step towards some greater whole?

253~54페이지에 있는 일련의 다이어그램에서 해답을 찾을 수 있으며, 매우 간단한 반복 과정을 보여줍니다. 다이어그램 행렬의 각 행에는 특정 날짜의 특정 구성이 표시되고, 그 구성 당시 볼 수 있었던 잠재적 중심이 표시되고, 잠재적 중심을 강화하고 강화하기 위해 새로운 건설이 수행될 위치에 대한 결정을 나타내는 어두운 덩어리가 표시되고, 건설 결과, 즉 해당 위치에 지어진 실제 건물 계획이 전체 구성을 새로운 고원으로 가져가는 것을 볼 수 있습니다. We may see the answer in the series of diagrams on pages 253~54, showing a very simple iterated process. In each row in the matrix of diagrams, we see a certain configuration at a particular date, then we see the latent centers that were visible at the time of that configuration, then we see a dark mass indicating the decision about where new construction would be undertaken to strengthen and intensify the latent center, and then we see the result of construction - the plan of an actual building built in that position taking the configuration as a whole to a new plateau.

다음 다이어그램 행에서는 새로운 구성에서 앞으로 나아가는 프로세스가 반복되는 것을 볼 수 있습니다. 반복된 프로세스를 10번 적용한 후, 이 프로세스를 통해 탄생한 아름답고 멋진 성 마르코 광장의 구성을 볼 수 있습니다. In the next row of diagrams, we see the process repeated, going forward from the new configuration. After ten applications of the iterated process, we see the beautiful, wonderful configuration of St. Mark's square as it arose from the process.

이 과정은 실제로 전체에 초점을 맞추고 전체에 의해 인도되었습니다. 그러나 매 순간 전체는 그 전체에 잠재된 중심과 함께 있는 그대로의 전체 구성에 주의를 기울임으로써 분별됩니다. 이 기법은 매우 일반적입니다. 항상 전체를 향상시킨다는 의미를 잘 이해하기 위해서는 보존하는 구조와 향상하는 구조의 관계를 명확하게 파악할 필요가 있습니다. 구조를 보존하는 변형과 구조를 강화하는 변형 사이의 관계는 정확히 무엇일까요? 겉보기에 서로 다른 이 두 가지 아이디어는 어떻게 조화될 수 있을까요? This process has indeed focused on the whole, and been guided by the whole. But the whole, at each moment, is discerned by paying attention to whole configuration as it is together with the centers latent in that wholeness. This technique is quite general. In order to understand well what it means "always to enhance the whole," we need to grasp clearly the relation between preserving structure and enhancing structure. What, precisely, is the relation between a transformation that is structure-preserving, and one that is structure-enhancing? How can these two apparently different ideas be reconciled?

설명을 위해 2장에서 처음 제시한 기본 이론으로 돌아가 보겠습니다. 한편으로는 구조를 보존하는 과정이 구조를 변형하고 보존하며, 다른 한편으로는 이러한 구조를 보존하는 변형이 전체를 향상시킨다는 생각입니다. 모든 전체성, 모든 구조에는 잠재적 중심이 존재하기 때문에 이 둘은 화해할 수 있습니다. 이러한 중심은 전체 구성에 의해 발생하며 구조에 희미하게 존재하지만 아직 완전히 발달하지 않은 중심입니다. 이러한 센터는 구조의 일부이며 실제로 존재하며 존재합니다. 그러나 그들은 개발할 수 있는 능력이 있음에도 불구하고 아직 개발되지 않았습니다. 이러한 잠재적 센터를 개발하는 것은 기존의 구조를 존중하는 동시에 아직 태어나지 않은 새로운 구조로 향하는 길을 닦는 것입니다. 그 후 나타나는 구조는 새로운 구조이지만 이전 구조에 뿌리를 두고 있습니다. To explain, I go back to basic theory first presented in chapter 2. The idea is that a structure-preserving process on the one hand transforms and preserves structure and on the other hand the idea that this structure-preserving transformation then also enhances the whole. The two can be reconciled, because in every wholeness, in every structure, there are latent centers. These are centers caused by the overall configuration, dimly present in the structure, yet not yet fully developed. These centers are part of the structure, they are truly there, they are present. But they have not yet been developed, even though they are capable of development. In developing these latent centers, one is then both respecting the structure which exists, yet also paving a path to some as-yet unborn new structure. Even though the structure which then emerges is a new one, it has its roots in the old structure.

이를 올바르게 수행하고 이 보수적이고 생명력 있는 출현을 위한 길을 열려면, 존재하는 구조와 그 전체를 보존하는 동시에 그 전체를 강화해야 하며, 이는 아직 완전히 인식되지 않은 잠재적 중심을 강화하는 것을 의미합니다. To do this right, and to pave the way to this conservative and life-giving emergence, one must both preserve the structure which exists, and its wholeness, yet also enhance the wholeness - and that means enhancing the latent centers, those that are not yet fully recognized.

5. The Modern Problem of Design

이 원칙을 보다 일반적인 사례에 적용하는 방법을 이해하기 위해 디자인 프로세스를 예로 들어 보겠습니다. 물론 디자인 자체는 하나의 프로세스이며, 다른 모든 프로세스와 마찬가지로 디자인된 결과물의 품질은 이 프로세스의 품질에서 비롯됩니다. 그렇다면 디자인 프로세스는 디자이너의 머릿속에 살아있는 프로세스가 지배할 때 어떤 모습일까요? 모든 디자이너가 말하듯이 디자인 프로세스에서 가장 중요한 것은 첫 번째 단계입니다. 형태를 만드는 처음 몇 번의 획에는 나머지 단계의 운명이 담겨 있습니다. To understand the application of this principle to a more general case, let us take next an example of a process of design. Design itself, of course, is a process and, as in every other process, the quality of what is designed will flow from the quality of this process. What then, is a design process like when it is governed by a living process in the designer's mind. As any designer will tell you, it is the first steps in a design process which count for most. The first few strokes, which create the form, carry within them the destiny of the rest.

그렇다면 살아있는 프로세스에서 아름답고 일관된 전체가 형성되기 시작하려면 어떻게 디자인의 첫 단계를 밟아야 할까요? How then, in a living process, do we take the first steps of design so that a beautiful, coherent whole begins to take shape?

물론 초기 단계에서는 광범위한 구조, 즉 전체의 출현 구조에 집중해야 합니다. 문제는 이 초기 과정에서 형태의 출현에 대한 적절한 표기법이 없다는 것입니다. 건축가들이 전통적으로 사용하는 표기법은 드로잉이나 컴퓨터 표현의 언어입니다. 이 표기법을 사용하여 아이디어를 엿본 다음 이를 간단한 스케치 또는 간단한 모델로 기록하려고 합니다. 그러나 이러한 스케치에는 항상 너무 많은 정보가 너무 일찍 포함되어 있기 때문에 스케치(또는 컴퓨터 그림)는 항상 지나치게 구체적입니다. 스케치와 컴퓨터 그림은 매력적이고 흥미로울 수 있습니다. 하지만 스케치에 포함된 정보의 20%만 디자이너의 머릿속에서 실제 프로세스를 통해 내린 결정에 근거한 것이고 나머지 80%는 표기법(스케치)이 요구하기 때문에 도면에 입력한 임의의 내용이라면 문제가 발생할 수밖에 없습니다. In the early stage we must concentrate, of course, on broad structure, on the emergent structure of the whole. A difficulty is that we do not have a good notation for the emergence of form during this early process. The notation that architects traditionally use is a language of drawing or computer representation. Using this notation, we try to get the glimpse of an idea, and then put this down as a simple sketch, or as a simple model. But such a sketch always includes too much information, too early, so that the sketch (or computer drawing) is invariably over-specific. Sketches and computer drawings are seductive and may be interesting. But if only 20% of the information in a sketch is based on real decision that have been taken by a living process in the designer's mind, and the remaining 80% is arbitrary stuff entered into the drawing only because the notation (sketching) requires it, trouble inevitably follows.

따라서 우리는 매 순간 실제로 알려진 것에 근접한 새로운 형태를 표현할 수 있는 표기법 또는 방법이 필요합니다. 여기서 저는 형태론적 "잔물결(ripple)"이라는 개념을 소개하고자 합니다 형태학적 잔물결이란 부분적으로 생성된 형태로, 고려 중인 공간에 어떤 전체적인 구성이 존재하지만 아직 명확하게 위치하거나 치수가 정해지거나 특성화되지 않은, 모호하지만 전체의 어떤 특징을 확고하게 설정하고 최종 결과에 성격과 느낌을 부여하는 데 결정적인 역할을 하는 필드와 같은 구성입니다. We therefore need a notation, or a way of representing emerging form, which stays close to what is actually known at each moment. Here I wish to introduce the idea of morphological "ripples." What I mean by a morphological ripple is a partially generated form, in which some global configuration exists in the space under consideration, but it is not yet clearly located, or dimensioned, or even characterized - it is a fieldlike configuration which, though fuzzy, firmly sets some feature of the whole, and plays a decisive role in giving character and feeling to the end result.

첫 번째 단계인 형태적 파급은 새로운 디자인의 가장 광범위하고 글로벌한 특징에만 초점을 맞추는 것이 중요합니다. 이러한 "글로벌" 특징은 종종 고려 중인 영역의 전체 지름을 가로질러 확장됩니다. 각 단계에서 또 다른 물결(ripple)이 전체에 또 다른 특징을 하나 더 도입합니다. 이러한 잔물결을 왜곡 없이 담아내려면 종이나 컴퓨터 화면의 도면이 아니라 머릿속으로, 가급적이면 실제 장소에 서서 작업하는 것이 가장 좋지만, 최소한 건물과 지형의 광범위한 특징을 3차원으로 보여주는 매우 사실적인 모델이 있는 상태에서 작업하는 것이 가장 좋다고 생각합니다. It is important that the first steps - the morphological ripples - should focus only on the broadest, most global features of the emerging design. Often these "global" features will extend cross the full diameter of the area being considered. At each step, another "ripple" introduces one more feature of the whole. To contain these ripples without distortion, I find it best to work, not on paper, not in a drawing on the computer screen, but in the mind's eye, preferably while standing in the real place itself - but at the very least in the presence of an extremely realistic model showing the broad features of buildings and terrain in three dimensions.

종이에 스케치하는 것이 아니라 마음의 눈으로 새로운 건물에 대한 비전을 형성하는 것이 중요합니다. 눈을 감고 볼 때 단어와 인테리어 비전은 스케치나 물리적 디자인보다 더 불안정하고 유동적이며 변형 가능하고 입체적입니다. 따라서 전개가 더 성공적으로 진행될 수 있습니다. 마음의 눈에서 살아있는 과정 속에서 하나씩 진화하는 센터는 너무 일찍 오는 임의의 정보와 결정에 의해 방해를 받지 않습니다. It is essential to form this vision of the emerging building in your mind's eye, not in sketches on paper. Words and interior visions, when seen with your eyes closed, are more labile, more fluid, transformable and three-dimensional, than sketches or physical design. They allow the unfolding to go forward more successfully. In the mind's eye, the centers which evolve, one by one within the living process, are not hampered by arbitrary information and decisions that come too early.

따라서 드로잉 패드와 컴퓨터 화면은 전개 과정에 적합한 미디어가 아닙니다. 살아있는 프로세스가 쉽게 작동할 수 있는 미디어가 아닙니다. Thus the drawing pad and computer screen are poor media for an unfolding process. They are not media where a living process can easily go to work.

이와는 대조적으로, 새로운 건물을 위한 형태의 진화를 위한 최고의 캔버스는 내면의 눈, 마음의 눈입니다. 마음의 눈에는 실제로 살아있는 과정에서 생성되지 않은 비전이 거의 포함되어 있지 않습니다. 눈을 감으면 단어 그림에서 발생하는 특정 사물을 볼 수 있습니다. 단어 그림은 실제로 당신이 지금까지 내면의 눈에서 본 것을 포착합니다. 그리고 눈을 감고 있을 때 작동하는 마음의 눈은 단어와 동일한 힘을 가지고 있습니다. 실제로 보이지 않는 것을 추가하는 것은 거의 없지만, 추가하는 것은 실제적이고 본질적이며 유연합니다. 마음속에서 떠다니는 선명한 그림으로, 정의하고 싶은 측면에서만 정의되고 다른 측면에서는 정의되지 않은 비전이 떠오릅니다. By contrast, the best canvas for evolution of form for a new building is the inner eye, the mind's eye. The vision in the mind's eye contains little that is not actually generated by the living process. When you close your eyes, you see certain things which arise from the word picture. The word-picture, indeed, captures just what you have seen, so far, in your inner eye. And the mind's eye, as it works when your eyes are closed, has the same power as the words. It adds little that is not actually seen, but what it does add is real, and germane, and flexible. The vision floats in your mind, a hovering clear picture, defined only in those aspects you want to define, and undefined in others.

이러한 비전을 머릿속에 구축하는 과정은 그 자체로 차별화 과정을 단계별로 따라야 합니다. 비전은 한 번에 하나의 형태적 특징으로 구축됩니다. 먼저 건물에서 가장 중요한 한 가지를 스스로에게 말하고 보는 것으로 시작합니다. 건물의 높이, 위치, 품질, 색상이 바로 그것입니다. 건물에서 나오는 음울한 빛일 수도 있고, 건물 앞에 있는 정원일 수도 있고, 건물로 이어지는 정원일 수도 있습니다. 어떤 경우든 눈을 감고 상황에 따라 건물을 상상할 때 가장 먼저 보이는 건물의 전체적인 측면입니다. The process of building such a vision in your mind must itself follow the differentiating process, step by step. The vision is built one morphological feature at a time. You start by saying to yourself, and seeing, one thing, the most important thing about the building. That will be capture in its height, its position, is quality, its color. It might be a brooding light that emerges from the building, or it might be the gardens which precede it, and lead to it. It is, in any case, the first global, holistic aspect of the building which you see, when you close your eyes and imagine the building as the context requires that it should be.

6. At Each Step Decide Only What You Know With Certainty

기본 프로세스를 몇 번이고 반복하고 필요에 따라 15가지 변형을 적용하는 과정을 거치면서 한 번에 하나의 기능이 구축됩니다. 첫 번째가 확실해지면 두 번째를 추가합니다. 첫 번째와 두 번째에 확신이 들면 세 번째를 추가합니다. As the living process goes forward, repeating the fundamental process again and again, and applying the fifteen transformations as needed, one feature is built up at a time. When we are sure of the first, we add a second. When we are sure of the first and second, we add a third.

반드시 수행해야 하는 이러한 단계와 그 순서를 어떻게 결정하나요? (11장 참조). 어떤 단계를 어떤 순서로 수행하나요? 제가 생활 과정의 지침으로 드릴 수 있는 가장 기본적인 지침은 확실성을 가지고 움직이라는 것입니다. 즉, 당신이 아는 것에 대해서만 결정하면서 한 번에 하나씩 작은 발걸음을 내딛는 것입니다. 추측이나 "이렇게 해보면 어떨까?"라는 식의 단계는 절대 밟지 않습니다 대규모의 시행착오, 어둠 속에서의 사격은 효과가 없습니다. 그보다는, 느리고 작은 결정을 내리고, 한 가지를 결정하고, 그에 대해 확신을 갖고, 그리고 다음 단계로 넘어가는 것이 좋습니다. 당면한 작은 문제 하나에 대해 옳았다는 확신이 들면 그때 다음 작은 결정으로 넘어갑니다. How do you determine these steps which must be taken, and their sequence? (see also chapter 11). What steps do you take, in what order? The most basic instruction I can give you as a guide for a living process, is that you move with certainty. That means, you take small steps, one at a time, deciding only what you know. You try never to take a step which is a guess or a "why don't we try this?" Large-scale trial-and-error, shots in the dark, simply do not work. Rather, you move by slow, small decisions, deciding one thing, getting sure about it, and then, moving on. When - on the one particular small issue at hand - you feel certain enough that you have it right, then you move on to the next small decision.

작은 결정으로 움직여야 한다고 말할 때, 결정의 물리적 규모가 작아야 한다는 뜻이 아닙니다. 오히려 각 결정의 내용이 특정 주제, 디자인의 일부 기능으로 제한되고 다른 문제와 단절되어 어느 정도는 그 자체로 부유해야 한다는 의미입니다. When I say that you should move in small decision, I do not mean that the decisions should be small in physical scale. Rather, I mean that the content of each decision should be limited to a particular subject, to some feature of the design, disconnected from other matters, and floating, to an extent, by itself.

결정의 규모에 관한 한, 그것은 반대로 다소 커야합니다. 특히 처음에는 가장 큰 질문을 중심으로 작업해야 합니다. 작업의 초기 단계에서 해결해야 하는 많은 문제는 디자인의 전체적인 글로벌 품질과 관련이 있습니다. As far as the scale of the decisions is concerned - that, on the contrary, should be rather large. At the beginning, especially, you need to work mainly with the largest questions. Many of the issues you need to settle, in the early stages of your work, have to do with the whole, the global quality of the design.

첫걸음을 잘 내딛는 것은 언제나 중요합니다. 각 단계는 어떤 의미에서 전체로 돌아가는 것이며 "첫 걸음"으로 다시 시작하는 것입니다 따라서 좋은 첫걸음을 내딛기 위해서는 여러 가지 잘못된 첫걸음을 피하는 것이 가장 중요하다는 점을 인식해야 합니다. 수치로 비교하는 것이 유용합니다. 예를 들어 프로세스의 특정 단계에서 100개의 가능한 다음 단계가 있고 그 중 하나를 선택해야 한다고 가정해 보겠습니다. 일반적으로 이러한 가능한 다음 단계 중 좋은 것보다 나쁜 단계가 더 많다는 데 동의할 것입니다. 100개의 가능한 선택지 중에서 상황을 악화시키는 다음 단계는 90~95개 정도이고, 상황을 개선하는 다음 단계는 5~10개 정도로 상대적으로 적을 수 있습니다. 우리가 확신할 수 있는 것은 좋은 단계보다 나쁜 단계가 더 많다는 것입니다. 그렇다면 소수의 좋은 단계는 어떻게 찾을 수 있을까요? 우리가 가능성을 고려할 때 우연히 소수의 좋은 다음 단계 중 하나를 맞출 수 있을 만큼 운이 좋아야 할 특별한 이유는 없습니다. It is always crucial to take a good first step. Each step is, in a sense, a return to the whole and a starting over with a "first step." So, in the same breath, we must recognize that to take a good step, the main problem is to avoid taking any of the many possible false steps. A numerical comparison is useful. Suppose, for example, that at a given stage in a process there are a hundred possible next steps available and we must choose among them (the next decision in the design). It will generally be agreed, I think, that more of these possible next steps are likely to be bad than good. Of the 100 possible choices, there may esaily be as many as 90 or 95 next steps which will make the thing worse, relatively few, say 5 or 10 next steps which will make it better. What we can be sure of is that there are more bad steps than good ones. How, then, do we find the few good ones? There is no special reason that we should be lucky enough to hit one of the small number of good next steps, by accident, as we consider the possibilities.

이를 추론해 보면 다음과 같은 결론을 내릴 수 있습니다. 우리 마음에 가장 먼저 떠오르는 가능성은 좋은 가능성보다는 나쁜 가능성일 가능성이 더 높습니다. 따라서 우리는 처음 떠오르는 가능성에 대해 극도로 회의적이어야 합니다. 우리는 가능성을 매우 빠르게 실행하고 대부분의 가능성을 거부해야 합니다. 만약 우리가 하나를 받아들인다면, 우리는 마지못해 마지못해, 마침내 그것을 거부 할 좋은 이유가없는, 우리에게 진정으로 훌륭해 보이고, 전체의 느낌을 더욱 심오하게 만드는 무언가를 만났을 때만 그것을 받아 들여야합니다. If we reason this out, we may then draw the following conclusion. It is more likely that the first possibilities that present themselves to our minds will be bad ones, rather than good ones. We should therefore be extremely skeptical about the first possibilities that present themselves to our minds. We should run through the possibilities very fast, and reject most of them. If we do accept one, we should accept it, reluctantly, only when we finally encounter something for which no good reason presents itself to reject it, which appears genuinely wonderful to us, and which demonstrably makes the feeling of the whole become more profound.

이것은 건축가가 일반적으로 사용하는 행동이 아닙니다. 오히려 건축가는 "영감이 떠오를 것"이라고 기대하는 경우가 더 많습니다 건축가는 자신의 창의성에 집착하여 자신이 결정한 것에 뛰어들고, 검토하지 않고 죽도록 사랑하지만 그것이 영감에서 나온 것이라고 믿기 때문에 계속 진행합니다. This is not the behavior that an architect typically uses. Rather what happens often is that the architect expects that "inspiration will strike." He is - too often - obsessed with his own creativity - jumps at what he has determined - and then loves it to death, unexamined, but goes on with it because he believes that it came from inspiration.

그러나 물론, 단순히 떠오르는 이미지에 뛰어 들고 자신의 머릿속에서 떠 올랐기 때문에 반드시 좋아야한다는 자기기만적인 생각을 가지고 있다면 이 첫 번째 또는 두 번째 또는 세 번째 "영감"이 좋은 것이 아니라 나쁜 것일 가능성이 큽니다. 또한, 건축가가 아이디어를 따르거나 이전에 보지 못한 인상을 만들고자 하는 욕구로 인해 의도적으로 왜곡될 가능성도 프로세스를 모호하게 만들고 막다른 골목으로 이끌 수 있습니다. But of course, if one merely jumps at the image that presents itself, and if one carries a self-deluded idea that it must be good because it came up in one's own brain - the chances are great that this first or second, or third "inspiration" is something not good, but more likely something bad. Further, the possibility of willful distortion, caused by the architect following an idea or a desire to create a never-before-seen impression, is also capable of obscuring the process, and leading it up a blind alley.-

근대 및 포스트모던 건축의 거의 모든 충격적인 실수와 공포는 이렇게 이해될 수 있습니다. 그들은 주로 실험적으로 조사되지 않았기 때문에 나쁜 것으로 판명되었습니다. 디자이너는 형태의 진화에서 가능한 여러 단계를 검토하고 각 단계에서 가장 깊은 느낌을 주는 것, 즉 가능한 단계 중 어떤 단계가 그 장소에서 세계를 확장하고 보호하는 데 가장 적합한지를 신중하게 찾으려고 시간을 할애하지 않았습니다. ~-Virtually all the shocking blunders and horrors of modern and postmodern architecture may be understood like this. They turned out bad mainly because they were unexamined experimentally. The designer did not take the time to examine the different possible steps in the evolution of the form and, at each step, seek out - with care - that one of these which has the deeptest feeling: hence which of the possible steps does the most to extend and protect the world in that place.