wholeness, center, coherence, 15 properties

Contents

Preface

7. A New Vision of Architecture

현재의 건축학적 질서에 대한 관점에서, 기능은 지적으로 이해할 수 있는 것입니다. 이는 카르테시안 기계론적 규범을 통해 분석될 수 있습니다. 반면에, 장식은 우리가 좋아할 수는 있지만 지적으로 이해할 수 없는 것입니다. 하나는 진지한 것이고, 다른 하나는 경박한 것입니다. 따라서 장식과 기능은 서로 분리됩니다. 건축물을 기능적이면서 동시에 장식적인 것으로 볼 수 있게 하는 질서에 대한 개념은 없습니다. In present views of architectural order, function is something we can understand intellectually; it can be analyzed through the Cartesian mechanistic canon. Ornament, on the other hand, is something we may like, but cannot understand intellectually. One is serious, the other frivolous. Ornament and function are therefore cut off from each other. There is no conception of order which lets us see buildings as both functional and ornamental at the same time.

이 책에서 내가 설명하는 질서의 관점은 매우 다릅니다. 이는 장식과 기능에 있어 공정합니다. 질서는 깊이 있게 기능적이며 깊이 있게 장식적입니다. 장식적 질서와 기능적 질서 사이에는 차이가 없습니다. 우리는 그것들이 다른 것처럼 보이지만 실제로는 하나의 질서의 다른 측면일 뿐임을 배우게 됩니다. The view of order which I describe in this book is very different. It is even-handed with regard to ornament and function. Order is profoundly functional and profoundly ornamental. There is no difference between ornamental order and functional order. We learn to see that while they seem different, they are really only different aspects of a single kind of order.

더 중요한 것은, 모든 질서의 기초로 내가 식별한 구조도 또한 개인적이라는 것을 우리는 보게 될 것입니다. 이를 이해하기 시작함에 따라, 우리 자신의 느낌, 한 개인으로서 뿌리내리고, 행복하며, 자기 자신 안에서 살아 있고, 단순하고, 평범한 느낌이 질서와 불가분의 관계에 있음을 볼 것입니다. 따라서 질서는 우리 인간성으로부터 멀리 떨어져 있지 않습니다. 그것은 인간 경험의 핵심에 속하는 바탕이 됩니다. 우리는 카르테시안 딜레마를 해결하고, 외부의 객관적 현실과 내부의 개인적 현실이 철저히 연결된 질서의 관점을 만듭니다. What is even more important, we shall see that the structure I identify as the foundation of all order is also personal. As we learn to understand it, we shall see that our own feeling, the feeling of what it is to be a person, rooted, happy, alive in oneself, straightforward, and ordinary, is itself inextricably connected with order. Thus order is not remote from our humanity. It is that stuff which goes to the very heart of human experience. We resolve the Cartesian dilemma, and make a view of order in which objective reality "out there" and our personal reality "in here" are thoroughly connected.

Part One

- What is living structure?

- What is life in buildings?

- What is a living world?

- What is the structure of a living world?

1. The Phenomenon of Life

1. Introduction

우리는 매우 특이한 과학적 문제에 직면해 있습니다. 20세기 말 현재 생물학계에서는 "생명"에 대한 유용하고 정확하며 적절한 정의가 존재하지 않습니다. 20세기의 전통적인 과학적 정설에 따르면 생명, 더 정확히 말하면 살아있는 시스템은 특별한 종류의 메커니즘으로 정의되어 왔습니다. "생명"이라는 단어는 특정한 제한된 현상 체계에만 적용되었습니다. 이 책에서는 이러한 개념이 바뀌어야 한다는 것을 보여줄 것입니다. "질서"는 공간의 특성으로 인해 발생하는 가장 일반적인 수학적 구조 체계로 이해할 수 있습니다. 그리고 "생명" 역시 이와 비슷한 일반성의 개념입니다. 실제로 제가 설명할 사물의 체계에서 모든 형태의 "질서"는 어느 정도의 "생명"을 가지고 있습니다. We find ourselves up against a very unusual scientific problem. Within biological sciences as they stand at the end of the 20th century, we do not have a useful, or precise, or adequate definition of "life". In traditional 20th-century scientific orthodoxy, life - or, to be more precise, a living system - has been defined as a special kind of mechanism. The word "life" has been applied only to a certain limited system of phenomena. We shall see, in this book, that this conception of things needs to be changed. "Order" may be understood as a most general system of mathematical structures that arises because of the nature of space. And "life" too, is a concept of comparable generality. Indeed, in the scheme of things I shall describe, every form of "order" has some degree of "life".

따라서 생명은 스스로 재생산하는 생물학적 기계에 적용되는 제한된 기계적 개념이 아닙니다. 생명은 우주 자체에 내재된 특성으로, 우주에 존재하는 모든 벽돌, 모든 돌, 모든 사람, 모든 종류의 물리적 구조에 적용됩니다. 모든 것에는 생명이 있습니다. Thus life is not a limited mechanical concept which applies to self-reproducing biological machines. It is a quality which inheres in space itself, and applies to every brick, every stone, every person, every physical structure of any kind at all, that appears in space. Each thing has its life.

우리는 생태학적 아이디어를 더 발전시켜야 합니다. 생명체에게 필요한 것은 이미 그 안에 씨앗으로 존재하는 것, 즉 생명에 대한 편협한 기계론적 생물학적 관점을 넘어 모든 것을 포용하는 생명 개념입니다. We need to push the ecological idea further. What it needs - what it already has, as a seed within it - is a conception of life which goes beyond the narrow mechanistic biological view of life, and somehow embraces all things.

이는 모든 것을 하나의 시스템으로 간주하고 그것을 온전하게 만들고자 하는 욕구에서 비롯됩니다. 건축에 대한 생태학적 관점을 취하고자 한다면, 우리는 자연스럽게 지구에서 우리의 임무가 자연의 야생 부분뿐만 아니라 건물과 도시에서 생명을 창조하는 것이라는 관점을 취하려고 노력합니다. 이는 단순히 존재하는 자연을 보존하는 것과는 전혀 다른 의미입니다. 그것은 인공적인 것과 자연적인 것에 생명을 함께 창조하는 것을 의미합니다. This arises from the desire to take everything as a single system and to make it whole. If we want to take an ecological view of architecture, we naturally try to take the view that our job on earth is to create life in buildings and in towns, not only in the "wild" part of nature. This is quite different from merely preserving the natural life which exists. It means creating life in man-made things and natural things together.

생명이 있고 살아 있는 비자연적 구조물을 적극적으로 창조하는 것은 단순히 자연을 보존하는 것 이상의 의미가 있습니다. 단순히 자연을 바라보며 "그대로 두자"라고 말할 수 있는 것이 아니라 발명해야 하기 때문에 훨씬 더 어렵습니다. 심지어 그것이 가능하다는 사실 자체가 엄청난 지적 어려움을 야기합니다. 그것을 이해하고, 정신적으로 파악하고, 그렇게 하기 위해서는 좁은 의미의 생물학적 의미에서 살아있는 조직과 무생물(다시 좁은 의미의 생물학적 의미에서 무생물) 사이의 관계를 명확히 하고 이해할 수 있는 사물에 대한 개념이 있어야 합니다. 우리는 수풀이 새, 흙, 비 등과 관련하여 살아 있기를 원할뿐만 아니라 창턱의 나무 조각, 화단 가장자리의 콘크리트 조각이 생명의 패턴에 어떻게 들어 맞는지 이해하고 그것을 완성해야합니다. 따라서 우리는 하나의 생명체에서 소위 살아있는 유기체와 소위 죽은 물질을 포함하는 하나의 생명 패턴을 추구합니다. 인간과 자연의 상호작용을 이해하고 그 상호작용을 통해 조화를 이루는 것, 그것이 바로 자연의 아름다움과 생명의 활기가 있는 것입니다. This active creation of non-natural structure which clearly has life, and which is alive, is very much more than merely preserving nature. It is much harder, to begin with, because it has to be invented; it is not a case of merely smiling at nature and saying, "Let's keep it that way". The fact that it is even possible poses enormous intellectual difficulties. In order to understand it, grasp it mentally, and to do it, we must have a conception of things in which the relation between living tissue, in the narrow biological sense, and non-living matter (again, non-living in the narrow biological sense), can be made clear and understood. We must not only want the bush to be alive with respect to birds, earth, rain, and so on, but we must also understand how the piece of wood in the windowsill, the piece of concrete in the edge of the flower bed fit into this pattern of life and complete it. Thus we are after one pattern of life, which includes the so-called living organisms and the so-called dead matter in a single living system. It is a case of understanding the interaction of man and nature, and making a harmony out of that interaction, which has the ceauty of nature and the zest of life.

2. The Need for a broader and More Adequate Definition of Life

어떤 도시나 건물, 또는 영국 남부의 300마일 길이의 거대한 구조물에 존재하는 자연과 인공의 혼합은 복잡한 정의의 문제를 제기하지만, 우리는 거의 답을 찾지 못하고 있습니다. 예를 들어 집의 서까래, 기와, 도로, 다리, 대문, 심지어 밭의 고랑까지, 이 모든 경우에서 우리는 분명히 '비생명체'가 생명체와 섞여 있는 것을 볼 수 있습니다. 일반적인 과학 용어로는 이런 것들을 생명체라고 부를 수 없습니다. 그러나 이러한 것들은 더 큰 시스템의 전반적인 삶에서 중요한 역할을 하는 것이 분명합니다. 우리가 순전히 기계론적인 생명의 그림을 고수한다면, 생태 순수주의자들이 실제로 자연을 "있는 그대로" 보존해야 한다는 생각에 갇혀 있는 것처럼, 우리는 가장 순수한 형태의 생태적 자연에 대한 보존주의적 고집에 갇히게 됩니다. 왜냐하면 이것이 그들이 원하는 것을 명확하게 정의할 수 있는 유일한 방법이기 때문입니다. 건물과 자연이라는 더 복잡한 시스템을 하나의 살아있는 시스템으로 취급하려는 순간, 우리가 하려는 일에 대한 적절한 과학적 정의가 없기 때문에 지적인 문제에 부딪히게 됩니다. 예를 들어, 오늘날의 생물학적 용어에 따르면 도시는 살아있는 시스템이 아닙니다. 사회 과학자들은 비유를 찾기 위해 종종 도시를 살아있는 시스템이라고 부르기도 하는데도요. The mixture of natural and man-made which exists in any city or any building - or in the huge 300-mile-long structure of southern England - raises complicated questions of definition, which we have hardly begun to answer. In all these cases we have obviously non-living systems mixed in with the living systems: for example, the rafters of a house, the foor tiles, the road, the bridge, the gate; even the furrows in the field. In normal scientific parlance, one could not possibly call these things alive. And yet clearly they do have a vital role in the overall life of the larger systems. If we adhere to the purely mechanistic picture of life, we are stuck with preservationist adherence to ecological nature in its purest form - just as ecological purists have in fact been stuck with the idea that they must keep nature "as it is", because this is the only way they can define clearly what they want to do. The moment we want to treat the more complex system of buildings and nature together, as one living system, we run into intellectural problems because we no longer have an adequate scientific definition of what we are trying to do. For example, according to present-day biological terminology, a city is not a living system, even though it is often referred to as a living system by social scientists in search of a metaphor.

이 책에서 저는 사물이 무엇이든 간에 각 사물에 어느 정도의 생명이 있다는 넓은 의미의 생명 개념을 찾고자 합니다. 돌멩이, 서까래, 콘크리트 조각 하나하나에는 어느 정도의 생명이 있습니다. 그러면 유기체에서 발생하는 특정 수준의 생명은 더 넓은 생명 개념의 특수한 경우에 불과한 것으로 간주됩니다. 지난 수십 년간 과학적 정통주의에 길들여진 귀에는 터무니없게 들릴지 모르지만, 저는 이 개념이 과학적으로 더 심오하고, 우주에 대한 수학적, 물리적 이해에 탄탄한 기반을 가지고 있으며, 무엇보다도 우리가 세상을 '살아 있게' 만들려고 할 때 세상에 대한 하나의 일관된 개념과 세상에서 우리가 하는 일에 대한 개념을 제공한다는 것을 보여 드리려고 노력할 것입니다. Thoughout this book, I shall be looking for a broad conception of life, in which each thing - regardless of what it is - has some degree of life. Each stone, rafter, and piece of concrete has some degree of life. The particular degree of life which occurs in organisms will then be seen as merely a special case of a broader conception of life. Although this may sound absurd to ears trained in the last few decades of scientific orthodoxy, I shall try to show that this conception is more profound scientifically, that it has a solid basis in mathematical and physical understanding of space, and above all that it does provide us with a single coherent conception of the world, and of what we are doing in the world, when we try to make the world "alive".

3. A New Concept of "Life"

이 책에서 저의 목표는 이 개념, 즉 모든 것에 생명의 정도가 있다는 생각이 잘 정의된 과학적 세계관을 만드는 것입니다. 그러면 우리는 방 한 칸, 심지어 문고리 하나, 동네, 광활한 지역 등 이 세상에 생명을 창조하기 위해 무엇을 해야 하는지에 대해 매우 정확한 질문을 던질 수 있으며, 오래 전 영국 남부의 영국인들이 그랬던 것처럼 우리는 캘리포니아나 아시아 또는 전 세계 어느 지역에서든 다시 생명을 창조할 수 있습니다. My aim in this book is to create a scientific view of the world in which this concept - the idea that everything has its degree of life - is well-defined. We can then ask very precise question about what must be done to create life in the world - whether in a single room, even in a doorknob, or in a neighborhood, or in a vast region, where, as the English people of southern England did once long ago, we might again create life in large parts of California, or Asia, or indeed in any region of the world.

이 첫 번째 장에서는 우리가 사물에 다양한 정도의 생명이 있다는 것을 느끼며, 이러한 느낌은 거의 모든 사람이 강하게 공유하고 있다는 점을 예로 들어 설득하고자 합니다. As a background for our work, I shall in this first chapter simply try to persuade you, by example, that we do feel that there are differnt degrees of life in things - and that this feeling is rather strongly shared by almost everyone.

먼저 부서지는 파도에 대해 생각해 봅시다. 바다에서 파도를 볼 때 우리는 파도에 일종의 생명이 있다는 것을 확실히 느낍니다. 우리는 그들의 삶을 실제적인 것으로 느끼고 우리를 감동시킵니다. 물론 생물학의 좁은 기계론적 관점에서는 파도에는 생명이 없습니다(해초나 플랑크톤이 살고 있는 경우를 제외하면). 그러나 적어도 우리의 느낌에 관한 한, 파도가 부서지며 움직이는 것이 화학물질로 악취를 풍기는 공업용 수영장보다 더 많은 생명을 가진 물의 시스템처럼 느껴지는 것은 부인할 수 없는 사실입니다. 고요한 연못의 잔물결도 마찬가지입니다. Let us first consider the breaking wave. When we see waves in the sea, we do certainly feel that they have a kind of life. We feel their life as a real thing, they move us. Of course, in the narrow mechanistic view of biology there is no life in the wave (except insofar as it has seaweed or plankton living in it). But it is undeniable - at least as far as our feeling is concerned - that such a moving, breaking wave feels as if it has more life as a system of water than a industrial pool stinking with chemicals. So does the ripple on a tranquil pond.

금은 살아 있는 느낌입니다. 황철광이나 보석 가게에서 파는 금과는 다른 자연 발생 금의 독특한 노란색은 살아 있는 느낌을 주는 섬뜩한 마법의 정수가 있습니다. 이것은 금전적 가치 때문이 아닙니다. 백금이 원래 금전적 가치를 갖게 된 것은 바로 이 심오한 느낌을 지니고 있었기 때문입니다. 가치가 비슷한 자연 발생 백금이나 훨씬 더 가치 있는 로듐은 전혀 같은 생명감을 갖지 못합니다. Gold feels alive. The peculiar yellow color of naturally occurring gold, so different from pyrites, or from the gold in the jeweller's shop, has an eerie magic essence that feels alive. This is not because of its monetary value. It got its monetary value originally because it had this profound feeling attached to it. Naturally occuring platinum, comparable in value, or rhodium, which is far more valuable, do not have the same feeling of life at all.

우리는 종종 나무 조각을 보고 그 생명력에 감탄하지만, 다른 나무 조각은 더 죽은 것처럼 느껴지기도 합니다. 물론 나무가 한때는 살아있었다고 말할 수도 있지만, 정확한 생물학적 의미에서 보면 지금은 확실히 살아있지 않습니다. 하지만 우리는 한 조각의 나뭇결이 다른 조각보다 더 많은 생명을 가지고 있다고 느낍니다. We often see a piece of wood and marvel at its life; another piece of wood feels more dead. Of course, you may say that the wood was once alive. but again, in the exact biological sense, it is certainly not alive now. Yet we do feel that the grain of one piece has more life than another.

따라서 비-유기적 물리적 시스템의 세계에서 우리는 구분을 합니다. 우리는 생명이 있는 것처럼 보이는 경우와 없는 것처럼 보이는 경우, 그리고 그 사이에 있는 경우를 구분합니다. 생명에 대한 직관, 즉 인상은 다양한 물리적 시스템에 존재합니다. Thus, throughout the world of non-organic physical systems, we make distinctions. We recognize cases which seem to have a great deal of life, others which seem to have none, others in between. The intuition, or impression, of life exists in a wide variety of physical systems.

나중에 한 경우에 다른 경우보다 더 많은 생명이 있다는 느낌이 사물 자체의 구조적 차이, 즉 정확하고 측정할 수 있는 차이와 관련이 있다는 것을 알게 될 것입니다. 하지만 지금은 단지 어떤 다른 물리적 시스템에는 더 많은 생명감이 있고 다른 시스템에는 더 적은 생명감이 있는 것처럼 보인다는 직관을 기록하고 싶을 뿐입니다. We shall see later that this feeling that there is more life in one case than the other is correlated with a structural diference in the things themselves - a difference which can be made precise, and measured. But for now, I merely want to record the intuition that some different physical system appear to have more feeling of life and others less feeling of life.

4. The Feeling of Life in Organisms

우리는 사람에게서도 이러한 느낌을 받을 수 있습니다. 어떤 사람은 생기가 넘치고 그 생기가 주변의 모든 사람에게 전달될 수 있습니다. 다른 사람은 축 늘어져 반쯤 죽어 있습니다. 우리는 누군가가 더 살아있다는 느낌을 경험하고, 같은 사람이라도 다른 순간에 다른 사람에게서 삶의 정도를 느낍니다. 물론 그것이 그 사람의 실제 건강 상태와는 다른 경우도 있습니다. We may feel the same in a person. One person may be glowing with life, which transmits to everyone around. Another person is droopping, half dead. We experence the sensation that one is more alive, and feel degrees of life in different people - even in the same person at different moment. And there are, of course, cases where a person's actual health is different.

5. The Feeling of Life in Ecological Systems

생태학에서 정확한 공식이 점진적으로 등장하는 것을 넘어, 우리는 한 초원이 다른 초원보다 더 살아 있고, 한 개울이 다른 개울보다 더 살아 있으며, 한 숲이 다른 죽어가는 숲보다 더 평온하고 활기차고 살아 있다는 느낌을 받습니다. Beyond the gradual emergence of precise formulations in ecology, we do have the feeling that one meadow is more alive than another, one stream more alive than another, one forest more tranquil, more vigorous, more alive, than another dying forest.

여기서도 생태학자들이 공식화했든 그렇지 않았든 간에, 우리는 자연 세계에 대한 감정의 핵심을 이루는 본질적인 개념으로서, 그리고 세계에 대한 사실로서 우리에게 근본적인 자양분을 제공하는 살아있음의 정도를 경험합니다. Here again - almost regardless of what ecologists have managed, or not managed, to formulate - we experience degree of life as an essential concept which goes to the heart of our feelings about the natural world, and which nourishes us fundamentally, as a fact about the world.

6. Life in Ordinary Human Events

저는 책/TheTimelessWayOfBuilding의 첫 몇 장에서 매우 평범하지만 강렬하게 살아 숨 쉬는 건물과 장소의 특성을 묘사했습니다. 이 질에는 전반적인 기능적 해방감과 자유로운 내면의 정신이 포함됩니다. 그것은 우리를 편안하게 만듭니다. 무엇보다도 우리가 그것을 경험할 때 살아있음을 느끼게 해줍니다. I have described this very ordinary but intensely living quality of buildings and places in the first few chapters of The Timeless Way of Building. This quality includes an overall sense of functional liberation and free inner sprit. It makes us feel comfortable. Above all it makes us feel alive when we experience it.

삶이 가장 영적이면서 동시에 가장 평범할 때 발생하는 자유는 수피교도들이 말하는 것처럼 "신에 취했을 때", 즉 가장 무심하고 가장 자유로울 때 생깁니다. 이러한 상황에서 우리는 개념으로부터 자유로워지고, 우리가 마주하는 상황에 직접 반응할 수 있으며, 감정, 개념, 관념의 제약을 가장 적게 받습니다. 이것이 바로 선과 모든 신비주의 종교의 핵심 가르침입니다. 또한 우리 주변에 존재하는 온전함을 보고, 직접 느끼고, 그에 반응할 수 있는 상태이기도 합니다. 술집과의 연관성은 완전히 어리석은 것은 아닙니다. 때때로 악 그 자체인 술 취함은 진실을 더 명확하게 볼 수 있는 우리의 능력을 해방시켜 주기도 합니다. 로마인들은 in vino veritas라고 말했습니다. 억제력이 어느 정도 상실되면 행동하고 반응할 수 있는 자유가 진정으로 증가한다는 뜻입니다. The freedom which arises when life is at its most spiritual, and also most ordinary, arises just when we are "drunk in God", as the Sufis say - most blithe and most unfettered. Under these circumstances, we are free of our concepts, able to react directly to the circumstance we encounter, and least constrained by affectations, concepts, and ideas. This is the central teaching of Zen and all mystical religions. It is also the condition in which we are able to see the wholeness which exists around us, feel it directly, and respond to it. The association with bars is not entirely silly. Drunkenness, no doubt evil itself at times, also releases our ability to see the truth more clearly. The romans said in vino veritas. When we have some loss in inhibition, our freedom to act and react is often truly increased.

7. The Feeling of Life in Traditional Buildings and Works of Art

형식적, 기하학적, 구조적, 사회적, 생물학적, 총체적인 삶이 바로 저의 주요 대상입니다. 여기에는 우리가 역사적 사례에서 보았던 기하학적 구조의 심오한 삶(석고, 콘크리트, 타일, 색상과 모양의 삶)이 포함됩니다. 평범한 삶, 우리가 그곳에서 살아있음을 느끼게 하고 그곳에 사는 사람과 동식물의 행복한 일상을 가능하게 하는 행동과 사건도 포함됩니다. 그리고 생물학적 삶, 즉 건물 내부와 건물 사이에 존재하는 자연 시스템을 생물학적으로 건강하게 가꾸는 것도 포함됩니다. 어떤 경우에는 사물이나 사람, 행동, 건물에 깃든 생명이 정말 놀라운 수준의 강렬함에 도달하기도 합니다. 이는 예술 작품이나 사람의 삶, 또는 하루의 한 순간에서 일어날 수 있습니다. It is this very general life - formal, geometric, structural, social, biological, and holistic - which is my main target. It includes the profound life of the geometric structure that we have seen in historical examples (their plaster, concrete and tile, the life of their colors and shapes). It includes the ordinary life, the actions and events which make us feel alive there, and which allow a happy everyday life to exist for the people and animals and plants who live there. And it includes the biological life, the nurture of the natural system which exist in and among the buildings, so that they are biologically healthy. In a few cases, life in a thing, or in a person, or in an action, or in a building, reaches a level of intensity which is truly remarkable. This can happen in a work of art, or in a person's life, or in a moment of a day.

8. Life in Twentieth Century Buildings and Work of Art

전통 유물에서 느껴지는 깊은 생명력은 20세기에는 특히 건물에서 찾아보기 어렵습니다. 2권 NatureOfOrder/The Process of Creating Life에서 자세히 설명하겠지만, 20세기에는 생명을 창조하는 데 필요한 과정이 손상되었기 때문에 이러한 유물이 흔하지 않습니다. The feeling of deep life which occurs in traditional artifacts is less common in the 20th century - especially in buildings. It is uncommon because - for reasons which will become clear throughout Book 2, The Process of Creating Life, the processes needed to create life were damaged in the 20th century.

...

이러한 것들이 우리를 편안하게 만드는 이유는 우리가 그것들을 진정성 있는 것으로 인식하기 때문입니다. 우리가 그 안에서 느끼는 생명은 바로 이 진정성에서 비롯됩니다. 우리 시대에 살아있는 느낌을 주는 것을 만드는 것이 우리의 주된 의도이므로, 특히 우리에게 영감을 주는 것은 이러한 현대 버전입니다. 그것들은 우리 자신의 노력을 이끌어내는 발판입니다. 우리 시대의 삶을 형성하려는 우리 자신의 노력은 우리가 지금 발견한 20세기의 삶과 일치해야 하고, 우리가 지금 창조한 것과 일치해야 하기 때문에 가장 고무적인 일이며, 우리의 주요 목표입니다. These things make us comfortable, because we recognize them as genuine. The life we feel in them comes from this genuineness. Since it is our main intention to make things which feel alive in our own time, it is these modern versions which must especially inspire us. They are the springboard from which our own efforts must come. Our own effort to form life in our time, becuase it must be consistent with 20th-century life as we now find it, and as we have now created it, is the most inspiring thing of all, and our chief target.

이러한 생명을 만들어 내기 위해서는 먼저 생명이 어떻게 온전함에서 비롯되는지, 그리고 실제로 생명이 어떻게 온전함인지 알아야 합니다. 온전함은 우리 주변에 존재하며, 생명은 온전함에서 솟아납니다. 우리가 처한 모든 상황, 심지어 가장 평범한 상황에서도 그 안에는 생명을 위한 역량이 있습니다. To produce this life, we must first see how life springs from wholeness, and indeed how life is wholeness. Wholeness exists all around us, and life springs from it. Every situation we are in, even the most mundane, has the capacity for life in it.

편안한 평범함과 이미지의 결여는 현재 우리의 삶을 만들어내는 주요 요소입니다. 와이셔츠 차림의 남자, 주유소를 개조한 카페, 오래도록 사용할 수 있으면서도 작은 식물도 귀하게 여기는 포장, 작업장의 기계, 거대한 트럭의 장식, 새것 같지 않은 해먹, 책상 위 벽에 붙어 있는 사진, 상점 창문 일부의 페인트, 천 명이 춤을 추는 대형 텐트의 축제 분위기, 점심시간에 두 사람이 햇살 아래서 샌드위치를 먹고 있는 창고 하역장까지. 이러한 것들은 현재의 환경에서도 삶을 구성하는 평범한 것들입니다. 우리가 이해해야 할 것은 수천 가지로 표현되는 이 편안한 평범함과 현대 예술의 정점은 모두 동일한 구조에 의해 만들어지며, 이 구조가 성공할 때 삶이라는 것입니다. Confortable ordinariness and lack of "image" quality are the main things which produce life in our current situation. A man in his shirt-sleeves, a cafe which is a converted gas station, paving which is made to last a long time but also to honor small plants without being precious, machines in a workshop, the decoration on a giant trucking rig, a hammock which is not too new, a photograph pinned to the wall above a person's desk, paint on part of a shop window, the festive quality of a big tent with a dance for a thousand people, the loading dock of a warehouse where two people are eating a sandwich during their lunch break in the sun. These are ordinary things which make life, even in the present environment. What we need to understand, is that this comfortable ordinariness in its thousands of manifestation, as well as the high point of modern art, are all produced by the same structure - and that, when it succeeds, this structure is "life".

9. Intense Life in Ordinary Poverty

이 장에서 소개한 유물 중 일부는 매우 아름답습니다. 이러한 유물들은 너무 특별해서 소수의 특권층이 만들어낸 것이며, 수세기에 걸친 인류의 경험을 대표하지 못한다고 말할 수도 있습니다. Some of the artifacts I have shown in this chapter are very beautiful. It might be said that these things are too special, that they come from a small and privileged class of human artifacts, and that they are not representative of the vast majority of human experiences throughout the centuries of history.

그러나 삶의 질은 이런 의미에서 전혀 귀중하거나 "높은" 것이 아닙니다. 그것은 우리 일상의 가장 소박하고 평범한 측면에도 아주 쉽게 존재합니다. 이런 의미에서 마티스와 반 고흐의 작품에서 우리가 느끼는 위대한 삶은 다소 오해의 소지가 있습니다. 왜냐하면 더러운 오두막집이나 빈민가에서도 동일한 삶의 느낌이 발생할 수 있고 실제로 "건축" 작품과 같은 장소에서 발생할 가능성이 더 높기 때문입니다. But the quality of life is not precious or "high" in this sense at all. It exists also, quite easily, in the most humble and ordinary aspects of our daily lives. In this sense the great life we feel in works by Matisse and van Gogh is somewhat misleading - since the same feeling of life can occur, also, in a dirty hut or in a slum - and, indeed, is often more likely to occur in such a place that a work of "architecture".

10. The Task of Making Ordinary Life in Things

이제 저의 평범하고 평범한 노력으로 돌아가 봅시다. 저는 우리 모두가 소박한 편안함을 느낄 수 있는 건물, 벤치, 창문 등을 만들어 모두가 집처럼 편안하고 일상 생활에 도움이 될 수 있기를 바랍니다. Let us come back now to my ordinary and commonplace effort. I want it to be possible for us - all of us - to make buildings, benches, windows, which have that simple comfort in them, so that everyone feels at home, so that they support us in our daily life.

그러나 이 생명 유지의 필수 요소는 간단하지만 찾기 어려운 것으로 밝혀졌습니다. 20세기에는 여러 가지 복잡한 이유로 인해 이 개념이 거의 사라졌습니다. 무엇보다도 물질에 대한 몇 가지 심오한 개념들 - 처음에는 거의 멀고 상식적이거나 실용적이지 않은 것처럼 보이는 - 이 우리의 인식에서 제거되었기 때문에 물질이 사라졌습니다. 이러한 물질의 개념 중 가장 근본적인 개념은 생명은 공간 그 자체의 질이라는 것입니다. 햇볕 아래서 샌드위치를 먹으며 경험하는 지극히 평범하고 일상적인 삶은 우리 시대의 지적 지형에서 제거된 개념입니다. 그것을 다시 되살리려면, 우리는 이 평범하지만 엄청나게 깊은 세계에 대한 그림에 적합한 그림을 조심스럽게 만들어야 합니다. But it turns out that this life-supporting quality, simple as it is, is also elusive. It is largely missing from the 20th century, for a variety of complex reasons. It is missing above all because some deep conceptions of matter - at first almost remote, and apparently not common-sense or practical at all - have been removed from our awareness. First among these concepts of matter is the most fundamental one - that life is a quality of space itself. Life, that very ordinary commonplace life, which we experience eating a sandwich in the sun, is something that has been removed from the intellectual landscape of our time. To bring it back again, we have to construct, carefully, a picture of the world which is adequate for these ordinary - but immensely deep - pictures of how things are.

2. Degrees of Life

1. Differing Degrees of Life in Our Everyday Surroundings

5. The Illuminated Manuscript and the Auditorium detail

다른 경우에, 나는 비슷한 실험을 수행했다. 학생들에게 일루미네이티드 매뉴스크립트의 그림(1장에서 색상으로 보여진)을 강의가 진행되고 있는 강당의 벽과 비교해보라고 요청했다. 그 벽은 포스트모던 패션으로 둥근 황동 조명과 황동 스트립으로 장식되어 있었다. On another occasion, I did a similar experiment, asking students to compare a picture of an illuminated manuscript (as shown in color in chapter 1) with a section of the wall of the auditorium where the lecture was taking place -- a wall that was decorated in postmodern fashion with round brass lights and brass strips.

다시 한 번, 두 개 중에서 일루미네이티드 매뉴스크립트가 더 많은 생명을 가지고 있다는 데 강한 동의가 있었다. 하지만 이전과 마찬가지로, 어떤 학생들은 그 동의가주저하는 것이었다. 그들은 질문에 대해 짜증을 내며, 그것이 잘못되었거나 조작된 것이라고 느꼈다. Once again there was strong agreement that, of the two, the illuminated manuscript had more life. But as before, for some students their agreement was reluctant; they expressed themselves irritated by the question, and felt that it was false or "rigged".

이 불편함은 한 건축학 학생에 의해 표현되었고, 그는 그 비교가 불공평하다고 불평했다. 나는 그것이 불공평하다는 것이 무슨 뜻인지 물었다. 대답은 이런 음흉한 방식으로 현대 건축을 나쁘게 드러내는 것 같다는 것이었다. 다른 학생은 일루미네이티드 매뉴스크립트가 오래된 것이라고 불평했다. 나는 그것이 경험적인 질문, 즉 두 개 중에서 어떤 것이 당신의 직관적이고 즉각적인 느낌에 따라 더 많은 생명을 가지고 있는지를 묻는 것과 어떤 관련이 있는지 물었다. 대답은 다시금, 그것이 오래되었기 때문에 관련이 없고, 공정한 비교가 아니라고 돌아왔다. 그러나 이 시연의 요점은 사람들이 실제로 생명에 따라 사물에 반응한다는 것을 보여주는 것이었고, 그들은 종종 이에 대해 동의한다는 것이었다. 제기된 모든 반대 의견은 불평을 하는 사람들에게도 이것이 부인할 수 없는 것임을 보여주었다. 그래서 그러한 판단이 객관적일 수 있다는 아이디어를 도입함으로써, 이 시연은 학생들이 학교에서 배우고 있는 자의적이지 않음을 다시 한 번 드러내며 학생들을 불안하게 만들었다. The discomfort was voiced by one architecture student who complained that the comparison was "unfair". I asked what it meant to say that it was unfair. The answer came back that in some sneaky sense it seemed to be showing modern architecture in a bad light. Another student complained that the illuminated manuscript was "old". I asked what that had to do with the empirical question: which of the two has more life according to your intuitive, immediate feeling? The answer came back, again, that since it was old it was irrelevant, and it was not a "fair" comparison. But the point of the deomnstration was simply to show that people do, indeed, react to things according to the degree of life they have, and they they often agree about it. The very objections that were raised, showed that for the complainers, too, this was undeniable. And as such, by introducing the idea that such juedgements might be objective, the demonstrations cut, once again, to the root of the arbitrariness they were being taught in school, and made to students nervous.

3. Wholeness and the Theory of Centers

1. Introduction

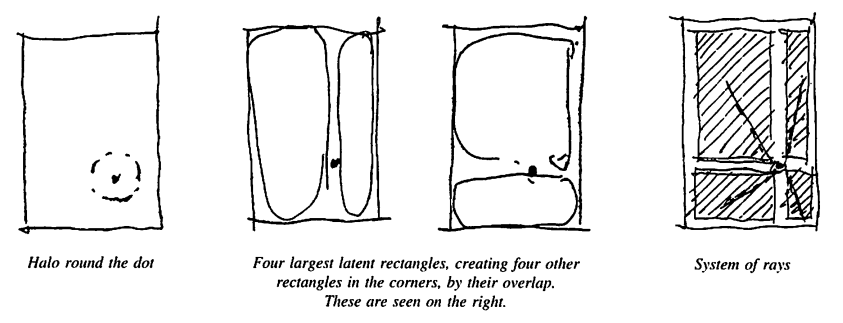

현상으로서의 생명(life as a phenomenon)을 이해하려면, 내가 "the wholeness"라고 부르는 그 무언가를 정의하는게 필요하다. 그리고 wholeness의 빌딩블록인, 내 용어로는 "centers"라고 부르는 crucial entities도 필요하다. 이 개념들은 다소 추상적이다. 이 정의들(wholeness, centers)로 인해, 우리는 to see the way that life comes about (chapter 4), the structural features which all life has (chapter 5), the nature of function and ornament (chapter 12)를 알 수 있다. 이 장의 내용들은 우리가 생명(life)을 구조(a structure)로서 이해하기 위한 기초작업을 하는 것이다.

2. The Idea of Wholeness

우리는 직관적으로 알 수 있다. 건축물의 아름다움, 생명, 생명을 지원(support)하는 능력(capacity) 이 모든 것들이 그것이 전체로서 기능한다는 사실(the fact that it is working as a whole)로부터 온다는 것을.

그런데 우리는 이것(wholeness)을 정확하게 설명하는 방법을 모른다.

<몇몇 설명들...>

이 모든 예시들에서, 전체(wholeness)가 가장 중요한 요소이다: 지역적인 부분들(local parts)은 전체와의 관계 속에서 존재(exist chiefly)하고, 그들의 행동과 특성, 구조는, 그들이 존재하고 그들이 만들어낸 더 큰 구조에 의해 결정된다.

몇 년 동안 생각한 후에, 나는 내가 정확한 언어로 what we mean by the wholeness of a given situation을 정의할 수 있게 되었다고 믿는다. 기본적인 생각은, 우리가 전체성을 구조로서 정확히 정의할 수 있다는 것이다. 이 구조는 부록에 수학적 언어로 정의되어 있다. 이후의 몇 쳅터에서는, 여러 예제들을 통해서, informal language로 이 아이디어를 설명하겠다.

3. An Example of the Wholeness in a Simple Case

the wholeness in any part of space는, 어떠한 구조(structure)인데, it is defined by:

- all various coherent entities, that exist in that part of space (centers?)

- and the way these entities are nested in and overlap each other. (relations between centers?)

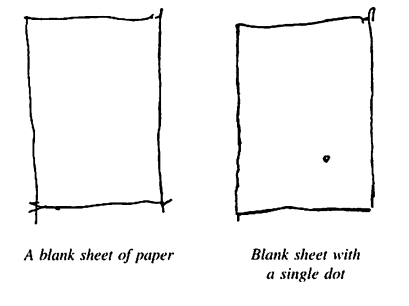

빈 A4 용지에 점을 하나 찍었을 때, segments of space를 간단하게 나열해볼 수 있다. 먼저 나오는 요소가 relative strength as entities:

- 종이 그 자체

- 점

- 점 주위의 halo

- 점 아래의 사각 영역

- 점 왼쪽의 사각 영역

- 점 오른쪽의 사각 영역

- 점 위쪽의 사각 영역

- 왼쪽 위 구석

- 오른쪽 위 구석

- 왼쪽 아래 구석

- 오른쪽 아래 구석

- 점에서 위로 뻗어나가는 선

- 점에서 아래로 뻗어나가는 선

- 점에서 왼쪽으로 뻗어나가는 선

- 점에서 오른쪽으로 뻗어나가는 선

- 이 선들로 인해 형성되는 흰 십자가

- 점에서 가장 가까운 종이 모서리로 향하는 선

- 점에서 그 다음 가까운 종이 모서리로 향하는 선

- 점에서 세번째로 가까운 종이 모서리로 향하는 선

- 점에서 가장 먼 종이 모서리로 향하는 선

전체성의 기본적(basic)인 아이디어는, 이 stronger zones or entities들이, 함께, define the structure which we recognize as the wholeness of the sheet of paper with the dot. 나는 이 구조(structure)를 전체성(wholeness)이라고 부른다.

4. The Origin of the Strength in Entities

5. The Concept of a Center

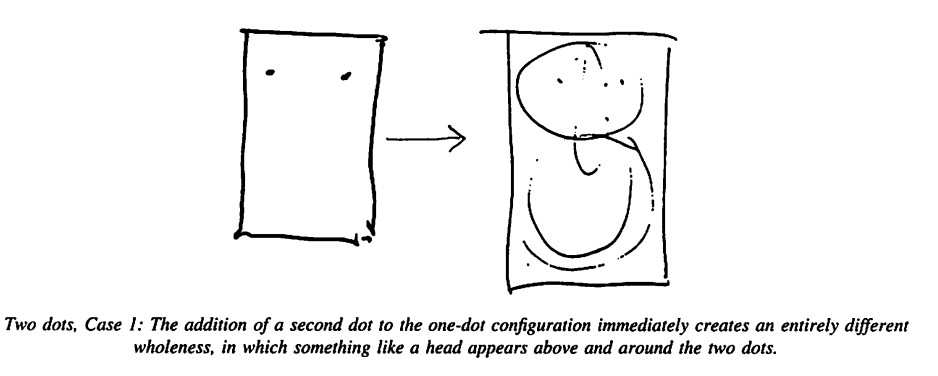

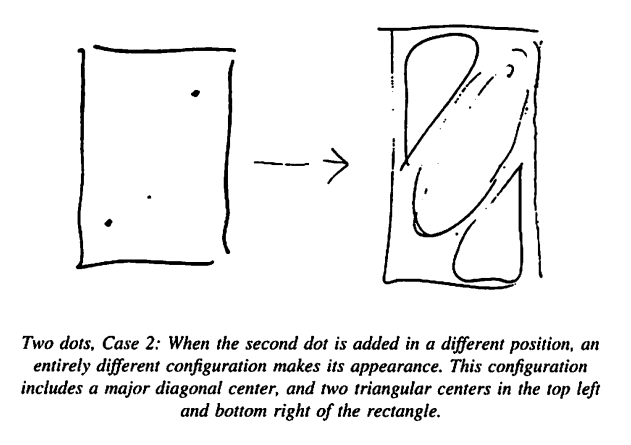

하지만, 내가 종이 한 장과 점의 사례에서 설명한 것처럼, 이러한 부분과 개체는 드물게 미리 존재한다. 그들은 더 자주 전체성(wholeness)에 의해 창조된다. 이 겉보기에 모순된 상황(단순한 방식으로 표현되었기 때문에 모순처럼 보일 뿐이다)은 전체성의 본질에서 근본적인 문제이다. 전체는 부분으로 이루어지며, 부분은 전체에 의해 창조된다. 전체성을 이해하기 위해서는 "부분"과 전체가 이러한 전체적인 방식으로 작동하는 개념을 가져야 한다. But, as I have illustrated in the case of the sheet of paper and the dot, these parts and entities are rarely pre-existing. They are more often themselves created by the wholeness. This apparent paradox (seeming paradoxical only because of the simple-minded way in which it is expressed) is a fundamental issue in the nature of wholeness: the wholeness is made of parts; the parts are created by the wholeness. To understand wholeness we must have a conception in which "parts" and wholes work in this holistic way.

이러한 실체에 대해 일관된 방식으로 이야기하기 위해, 최근 몇 년 동안 나는 이들 모두(부분이든, 지역적 전체이든, 거의 눈에 띄지 않는 일관된 실체이든)를 "중심"이라고 부르기 시작했다. 이것이 의미하는 바는, 각각의 실체가 "더 큰 전체 내에 지역적 중심으로 존재하는 것처럼 보이는 사실"이라는 그 정의적 특징을 가지고 있다는 것이다. 이것은 공간 내의 중심성 현상이다. To have a consistent way of talking about these entities, during recent years, I have learned to call them all (whether parts or local wholes or hardly visible coherent entities), "centers". What this means is that each one of these entities has, as its defining mark, the fact that it appears to exist as a local center within a larger whole. It is a phenomenon of centeredness in space.

이러한 방식으로 중심이라는 단어를 사용함에 있어, 나는 중력의 중심과 같은 점 중심을 전혀 언급하지 않는다. 나는 조직화된 공간 영역, 즉 내부의 일관성과 맥락과의 관계로 인해 중심성을 나타내는, 공간 내에서 상대적으로 중심성을 형성하는 지역적 영역인 공간의 구별된 점들의 집합을 식별하기 위해 중심이라는 단어를 사용한다. In using the word center in this way, I am not referring at all to a point center like a center of gravity. I use the word center to identify an organized zone of space -- that is to say, a distinct set of points in space, which, because of its organization, because of its internal coherence, and because of its relation to its context, exhibits centeredness, forms a local zone of relative centeredness with respect to the other parts of space.

세상에 있는 일관된 개체들을 전체가 아닌 중심으로 생각해야 하는 수학적인 이유가 있다. 만약 내가 전체에 대해 정확하게 이야기하고 싶다면, 그 전체가 어디서 시작하고 끝나는지를 묻는 것이 자연스럽다. 예를 들어, 내가 어류 연못에 대해 이야기하고 그것을 하나의 전체라고 부르고 싶다고 가정해 보자. 수학적 이론에서 그것에 대해 정확하게 말하기 위해, 나는 이 전체를 둘러싸는 정확한 경계를 그릴 수 있어야 하고, 공간의 각각의 점이 이 점들의 집합의 일부인지 아닌지를 말할 수 있어야 한다. 그러나 이것은 매우 어렵다. 분명히 물은 어류 연못의 일부이다. 그렇다면 그것이 만들어진 콘크리트는 어떠한가? 아니면 땅 아래의 점토는? 이것이 우리가 연못이라고 부르는 전체의 일부인가? 얼마나 깊이 내려가야 하는가? 연못 바로 위의 공기도 포함해야 하는가? 그것은 연못의 일부인가? 물을 가져오는 배관은 어떠한가? 이러한 질문들은 불편하고 결코 사소하지 않다. 연못을 정확히 포함하고, 배제해야 할 것들을 딱 맞게 잡아내는 자연스러운 방법은 없다. 매우 경직된 사고방식에서는 이것이 연못이 실제로 전체로 존재하지 않는 것처럼 보이게 만들 수 있다. 분명히 이것은 잘못된 결론이다. 연못은 존재한다. 우리의 문제는 연못을 정확하게 정의하는 방법을 모른다는 것이다. 하지만 그 문제는 그것을 전체라고 지칭하는 데서 온다. 그런 종류의 용어는 연못의 일부인 것들만 포함하고 그렇지 않은 것들은 제외하는 정확한 경계를 그릴 필요가 있는 것처럼 보이게 만든다. 그것이 실수이다. There is a mathematical reason for thinking of the coherent entities in the world as centers, not as wholes. If I want to be accurate about a whole, it is natural for me to ask where that whole starts and stops. Suppose, for example, I am talking about a fishpond, and want to call it a whole. To be accurate about it in a mathematical theory, I want be able to draw a precise boundary around this whole, and say for each point in space whether it is part of this set of points or not. But this is very hard to do. Obviously the water is part of the fishpond. What about the concrete it is made of, or the clay under the ground? Is this part of the whole we call "the pond"? How deep does it go? Do I include the air which is just above the pond? Is that part of the pond? What about the pipes bringing in the water? These are uncomfortable questions, and they are not trivial. There is no natural way to draw a boundary around the pond which gets just the right things, and leaves out just the right things. In a very rigid way of thinking, this would make it seem that the pond does not really exist as a whole. Obviously this is the wrong conclusion. The pond does exist. Our trouble is that we don't know how to define it exactly. But the trouble comes from referring to it as a "whole". That kind of terminology seems to make it necessary for me to draw an exact boundary, including just those things which are part of the pond, and leaving out just those which aren't. That is the mistake.

연못을 중심이라고 부를 때 상황이 달라진다. 나는 그 연못이 활동의 지역적인 중심으로서 존재한다는 사실을 인식할 수 있다: 즉, 살아있는 시스템이다. 그것은 집중된 개체이다. 그러나 그것의 경계가 모호하다는 문제는 덜 문제가 된다. 그 이유는 연못이 하나의 개체로서 그 중심을 향해 집중되어 있기 때문이다. 연못은 중심성을 가진 장(field of centeredness)을 창출한다. 그러나 명백히, 이 효과는 주변으로 갈수록 감소한다. 주변의 것들은 연못에서 그들의 역할을 한다. 하지만 나는 경계, 즉 무엇이 포함되고 무엇이 제외되는지에 대해 확고한 결정을 내릴 필요가 없다. 왜냐하면 그것이 요점이 아니기 때문이다. 일관된 개체로서 연못의 존재에 중요한 것은 연못의 조직이 여러 요소들이 함께 작용하여 중심 현상을 만들어내는 장(field effect)에 의해 발생한다는 점이다. 이는 연못의 실제 물리적 시스템에서 물리적으로 사실이다: 물, 경계, 얕은 곳, 경도, 수련 -- 이들은 모두 연못이 중심으로 형성되는 데 도움을 준다. 또한 이것은 내가 그 연못을 지각하는 정신적 측면에서도 사실이다. 그렇기 때문에 연못을 전체라고 부르는 것보다 중심이라고 부르는 것이 더 유용하고 더 정확하다. 창문, 문, 벽, 혹은 아치에 대해서도 같은 말이 성립한다. 이들 각각은 정확하게 경계가 설정될 수 없다. 이들은 모두 모호한 경계를 가진 개체이며, 그들의 존재는 주로 그들이 차지하는 세상의 일부에서 중심으로 존재한다는 사실에 있다. When I call the pond a center, the situation changes. I can then recognize the fact that the pond does have existence as a local center of activity: a living system. It is a focused entity. But the fuziness of its edges becomes less problematic. The reason is that the pond, as an entity, is focuesd towards its center. It creates a field of centeredness. But, obviously, this effect falls off. The peripheral things play their role in the pond. But I do not need to make a definite commitment about the edge, and what is in and what is out, because that is not the point. What matters in the existence of the pond as a coherent entity is that the organization of the pond is caused by a field effect in which the various elements work together to produce this phenomenon of a center. This is tru physically in the actual physical system of the pond: water, edge, shallows, gradients, lilies -- all help in the formation of the pond as a center. And it is also true mentally in my perception of that pond. That is why it is more useful, and more accurate, to call the pond a center rather than calling it a whole. The same is true for window, door, wall, or arch. None of them can be exactly bounded. They are all entities which have a fuzzy edge, and whose existence lies mainly in the fact that they exist as center in the portion of the world which they inhabit.

"전체"라는 용어보다 "중심"이라는 용어를 선호하는 또 다른 이유가 있다. 우리가 건축에서 다루는 개체들은 계단, 욕조, 문, 주방, 세 sink, 방, 천장, 출입문, 창문, 커튼 및 주방 구석과 같은 가장 일반적인 요소들이다. 궁극적으로 디자인을 다룰 때, 우리는 이러한 요소들 간의 적절한 관계가 무엇인지 질문해야 한다. 여기서도 "중심"이라는 용어를 사용하는 강력한 이유가 있다. 디자인에서 나타나는 관계의 관점에서 볼 때, 주방 세 sink를 "전체"라고 부르는 것보다 "중심"이라고 부르는 것이 더 유용하다. 만약 내가 그것을 전체라고 부르면, 그것은 내 머릿속에서 고립된 객체로 존재하게 된다. 그러나 내가 그것을 중심이라고 부르면, 그것은 나에게 추가적인 정보를 제공한다; 그것은 주방에서 sink가 어떻게 작용할지를 나에게 전달한다. 그것은 나로 하여금 더 큰 패턴을 인식하게 하고, 이 특정 요소인 주방 세 sink가 그 패턴에 어떻게 맞아들어가고 그 패턴에서 어떤 역할을 하는지를 깨닫게 한다. 그것은 sink가 자신의 경계를 넘어 뻗어나가고 주방 전체에서 자신의 역할을 하는 그런 존재처럼 느껴지게 만든다. There is yet another reason for preferring the term "center" to the term "whole". The entities we are concerned with in a building include the most ordinary elements like staircase, bathtub, door, kitchen, sink, room, ceiling, door, doorway, window, curtain, and kitchen nook. Ultimately, in dealing with design, we have to ask, What is the proper relationship among these elements? Here again there is a powerful reason for using the term "center". From the point of view of relationships which appear in the design, it is more useful to call the kitchen sink a "center" than a "whole". If I call it a whole, it thenexists in my mind as an isolated object. But if I call it a center, it already tells me something extra; it creates a sense, in my mind, of the way the sink is going to work in the kitchen. It makes me aware of the larger pattern of things, and the way this particular element -- the kitchen sink -- fits into that pattern, plays its role in that pattern. It makes the sink feel more like a thing which radiates out, extends beyond its own boundaries, and takes its part in the kitchen as a whole.

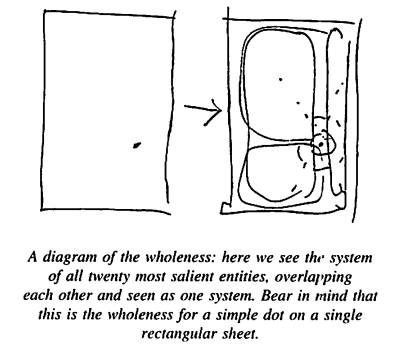

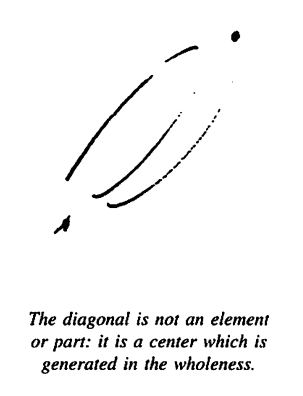

6. Wholeness as a Subtle Structure

주변의 전체성에 의해 중심이 유도되는 방식을 이해하기 위해, 다시 한 번 추상적인 예를 언급하자. 중심들이 항상 전체로서의 구성의 결과로서 중심이 된다는 점을 주목하는 것이 필수적이다. In order to understand the way that centers are induced by the surrounding wholeness, let us refer once again to abstract examples. It is essential to note that the centers always become centers as a result of the configuration as a whole.

따라서 특정 중심의 강도는 그 중심을 형성하는 내부 형태의 함수일 뿐만 아니라, 주어진 공간에서 바깥쪽으로 확장되는 많은 다른 요소들의 영향을 결과로 해서 생겨난다. 이 모든 것은 항상 전체로서의 구성의 결과이다. 이는 강도를 유발하는 수학적 특성의 목록에서 자연스럽게 나타난다. 대칭, 연결성, 볼록성, 동질성, 경계, 특징의 급격한 변화 등은 모두 전체로서의 구성의 함수이다. 특정 전체성을 구성하는 중심들은 독립적으로 존재하지 않으며, 전체로서의 구성에 의해 생성되는 요소로 나타난다. 지역 중심을 생성하고 지역 중심이 '안정되도록' 하는 것은 바로 구성의 대규모 특성이다. Thus the strength of any given center is not merely a function of the internal shape which creates that center in itself, but comes about as a result of the influence of many other factors which extend outward in the given region of space, always as a result of the configuration as a whole. This follow, anyway, from the list of mathematical features which are responsible for causing the strength. Symmetry, connectedness, convexity, homogeneity, boundaries, sharp change of features, and so forth are all functions of the configuration as a whole. The centers which make up any given wholeness do not exist independently, but appear as elements which are generated by the configuration as a whole. It is the large-scale features of the configuration which produce the local centers and allow the local centers to 'settle out'.

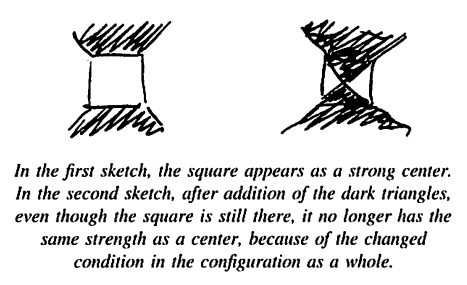

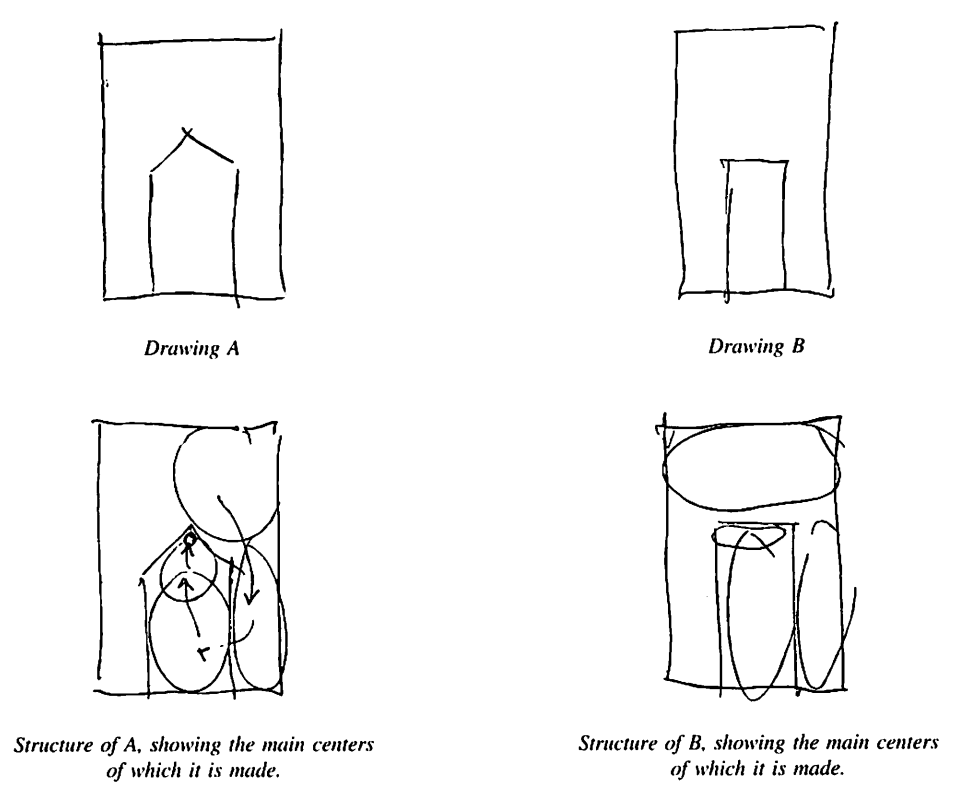

7. A Further Example of Wholeness as it is Captured by the System of Centers

A와 B라는 두 개의 아치 그림을 고려해보자. 이 그림들은 겉보기에는 다소 유사하지만, 그 느낌은 매우 다르다. 우리가 주의를 기울이면, 이 두 그림이 전체성(wholeness)으로 보았을 때 뚜렷하고 다른 게슈탈트를 가지고 있다는 것을 알 수 있다. Consider these two drawing of arches, A and B. The drawings are superficially somewhat similar, but the feeling they have is very different. We are aware, if we pay attention, that as wholes, they have a pronounced and different gestalt.

"A"는 아치 형태를 가지고 있으며, 아치의 정점 중앙에 뚜렷한 중심을 가지며, 전체적으로 일관성이 있다. "B"는 같은 형태의 더 간단한 직사각형 버전이다. 그러나 그 차이는 이 글자들이 제안하는 것보다 더 크다. 이 두 그림은 정말로 극명하게 다른 특성(character)을 가지고 있다. "A" has an arch form, a marked center in the middle at the point of the arch, and an overall coherence. "B" is a simpler, rectangular version of the same thing. But the difference is greater than these words suggest. The two really have extremely different character.

우리가 공간을 전체적으로 집중해서 보면, 그들이 얼마나 다른지 알 수 있다. 뾰족한 형태의 A는 아치의 정점에 초점이 맞추어져 있다. 그것은 통일되어 있다. 왼쪽과 오른쪽에 두 개의 쐐기 모양의 공간이 보이는데, 이는 날카로운 정점이 위의 공간을 거의 가르는 방식에 초점을 맞추고 있다. 그 점은 매우 강하게 강조되어 있다. 두 번째 아치인 B는 훨씬 더 둔하다. 우리가 주목하는 주된 것은 아치 위의 큰 비어 있는 공간의 고요함이다. 아치의 상단은 끌 형태로, 역시 고요하다. 양쪽에 있는 두 다리는 부속물로 보인다. 이 모든 것이 우리가 두 그림의 전체성(wholeness)이라고 의미하는 것이다. If we focus on the space as a whole, we see how different they are. The pointed one, A, has a focus on the point of the arch. It is united. One sees two wedge-shaped swarths of space to the left and to the right, emphasizing the way the sharp point almost cleaves the space above. The point is also very strongly marked. The second arch, B, is much more blunt. The main thing one is aware of is the stillness of the large square of empty space above the arch. The top of the arch, chisel shaped, is also still. One sees the two legs on either side as appendages. All this is what we mean by the "wholeness" of the two drawings.

Drawing A.

The wholeness that we experience -- The overall gestalt of the whole thing -- is precisely captured by the structure W.

Drawing B.

In this case the centers from a somewhat less coherent structure than in A.

두 그림 모두에서 중심의 시스템은 우리가 사물에서 직관적으로 경험하는 전체성을 묘사하고 있다. 그리고 우리는 전체성 W가 두 그림 사이의 생명의 차이를 묘사하고 설명하기 시작하는 방식의 힌트를 얻는다. A는 B보다 조금 더 많은 생명을 가지고 있으며, 이 사실은 A의 전체성에서 더 일관된 구조로 반영된다. In both drawings, the system of centers describes the wholeness we intuitively experience in the thing. And we have a hint of the way the wholeness W also begins to describe, and explain, the difference in life between the two drawings. A has more life than B, even if only slightly, and we find this fact reflected in the more coherent structure of its wholeness.

8. The Fundamental Entities of Which The World is Made

9. The Subtlety of Centers which Exist in the World

10. Wholeness as a Fundamental Structure

이 책에서 이어지는 모든 내용은 내가 정의한 전체성의 존재에 의해 지배받는 물리적 현실에 대한 관점이다. Everything that follows in this book is a view of physical reality dominated by the existence of wholeness as I have defined it.-

나는 물리적 현실에 대한 관점을 제안한다. 이 관점은 특정 구조, 즉 전체성 W의 존재에 의해 지배된다. 주어진 공간의 어떤 영역에서는 일부 하위 영역이 중심으로서 더 높은 강도를 가지고 있고, 다른 하위 영역은 덜 가지고 있다. 많은 하위 영역은 약한 강도를 가지거나 전혀 없는 경우도 있다. 중첩된 중심의 전체 구성과 그 상대적 강도는 단일 구조를 이룬다. 나는 이 구조를 그 지역의 전체성(wholeness)으로 정의한다. ~-I propose a view of physical reality which is dominated by the existence of this one particular structure, W, the wholeness. In any given region of space, some subregions have higher intensity as centers, other have less. Many subregions have weak intensity or none at all. The overall configuration of the nested centers, together with their relative intensities, comprise a single structure. I define this structure as "the" wholeness of that region.

나는 건물과 다른 인공물의 본질과 행동은 오직 이 구조의 맥락에서만 이해될 수 있다고 확고히 믿는다. 특히, 어떤 건물들이 다른 건물들보다 더 많은 생명을 가지고 있고, 객관적으로 더 아름답고 만족스럽다는 사실에 대한 객관적인 인식은, 내가 생각하기에, 이 구조의 맥락에서만 이루어질 수 있다. I am firmly convinced that the nature and behavior of buildings and other artifacts can only be understood within the context of this structure. In particular, objective recognition of the fact that some buildings have more life than others, and are objectively more beautiful and satisfying, can only -- I think -- be achieved in the context of this structure.

또한 나는 생명이 일반적인 생물학적 의미에서 이 전체성(wholeness)으로부터 생성된다고 믿는다. 그리고 이를 기계적인 방식으로 설명하려는 노력은 최근 수십 년 동안 실패해 온 것처럼 계속해서 실패할 것이라고 생각한다. I believe, too, that life, in an ordinary biological sense, is itself also created from this wholeness: and that efforts to explain it in more mechanical fashion will go on failing, as they have in recent decades.

전체성(wholeness)의 중요한 특징은 그것이 중립적이라는 것이다: 그것은 단순히 존재한다. 그 세부 사항의 결정은 중립적인 방법으로 이루어질 수 있지만, 동시에 -- 후속 장에서 보게 될 것처럼 -- 특정 건물의 상대적 조화 또는 생명은 구조의 내부 응집력에서 직접 이해될 수 있다. 따라서 특정 세계의 일부의 상대적 생명이나 아름다움, 선함은, 나는 주장할 것이다, 의견, 편견 또는 철학에 대한 언급 없이 단지 존재하는 전체성의 결과로서 이해될 수 있다. A crucial feature of the wholeness is that it is neutral: it simply exists. Determination of its details may be made by neutral methods, yet at the same time -- as we shall see in later chapters -- the relative harmony or "life" of a given building may be understood directly from the internal cohesion of the structure. Thus, the relative life or beauty or goodness of a given part of the world may be understood, I shall argue, without reference to opinion, prejudice or philosophy, merely as a consequence of the wholeness which exists.

11. The Global Character of Wholeness

12. Wholeness as a Fundamental Part of Physics

13. Wholeness as the Underlying Substrate of All Life in Space

14. Life Comes Directly from the Wholeness

4. How Life Comes from Wholeness

5. Fifteen Fundamental Properties

2.1. Levels of Scale

생명이 있는 물체(objects)들을 연구할 때 가장 먼저 알아챈 사실은, 그것들이 모두 서로 다른 크기(different scales)를 가지고 있었던 것. I would now say that,

- 이 물체들의 센터들은 are made of tend to have a beautiful range of sizes,

- and these sizes exist at a series of well-marked levels, with definite jumps between them

한 마디로 말해서, 큰 센터들, 중간 사이즈 센터들, 작은 센터들, 아주 작은 센터들.

만약 두 물건을 비교해서, 하나가 다른 하나보다 더 생명이 있다면, 아마도 그것은 그 안에 더 나은 levels of scale이 있을 가능성이 크다. The idea is far more subtle than it seems.

It is also extremely important that to have levels of scale within a structure, 서로 다른 스케일 간의 차이(jumps)는 반드시 너무 크지 않아야 한다.

2.2. Strong Centers

2.3. Boundaries

2.4. Alternating Repetition

2.5. Positive Space

2.6. Good Shape

2.7. Local Symmetries

2.8. Deep Interlock and Ambiguity

2.9. Contrast

2.10. Gradients

2.11. Roughness

2.12. Echoes

2.13. The Void

2.14. Simplicity and Inner Calm

2.15. Not-Separateness

3. The Nature and Meaning of the Fifteen Properties

4. The Interplay of the Properties

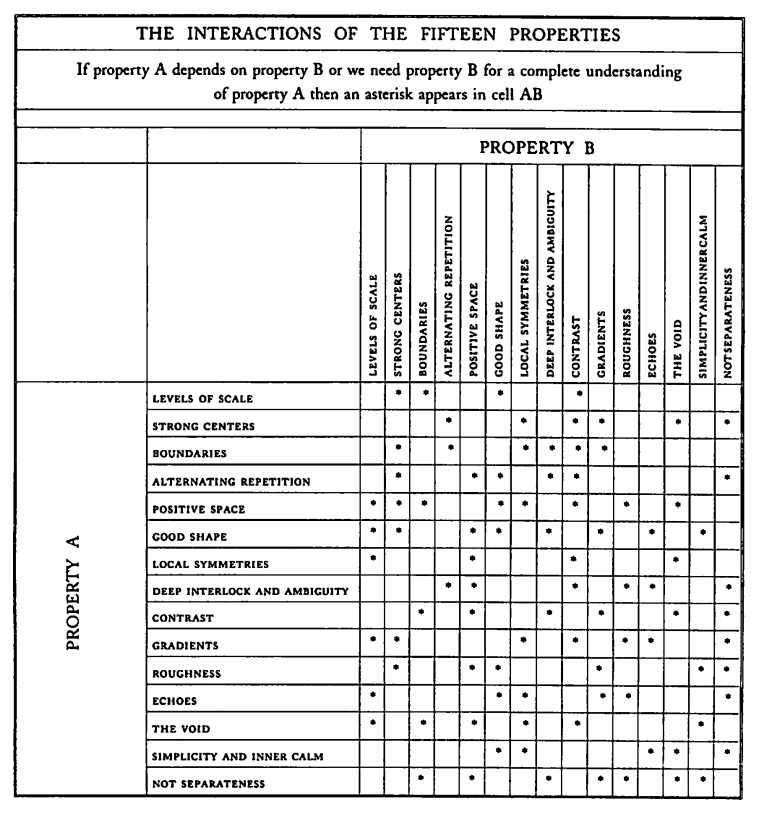

15 Properties 간에 dependency graph를 그릴 수 있다.

- Levels of Scale - Strong Centers, Boundaries, Good Shape, Contrast

- Strong Centers - Alternating Repetition, Local Symmetries, Contrast, Gradients, The Void, Not Separateness

- ...

이 graph에 대해 MDS를 그려서 클러스터링을 할 수 있다. (PURPLSOC: The Workshop 2014)

- Contrast, Not Separateness

- Roughness, Alternating Repetition, Good Shape

- Local Symmetries, The Void, Levels of Scale, Positive Space

- Boundaries, Strong Centers, Deep Interlock and Ambiguity

- Simplicity and Inner Calm, Echoes, Gradients

.

김창준님 clustering.

- 모여서 덩어리(clustering effect): positive space, good shape, local symmetry, levels of scale

- 장 효과(field-like effect): gradient, echo, alternating repetition, strong centers

- 명확성: contrast, boundary, void, simplicity and inner calm

- 모호성: not-separateness, deep interlock and ambiguity, roughness

5. How the Fifteen Properties Help Centers Come to Life

- Levels of Scale

- is the way that a strong center가, 그 안에 있는 작은 강한 센터들에 의해서 일부 강해지고, 또 그것을 포함하는 더 큰 센터들에 의해서 일부 강해진다.

- Strong Centers

- defines the way that a strong center requires a special field-like effect, created by other centers, as the primary source of its strength.

- Boundaries

- is the way in which the field-like effect of a center is strengthened by the creation of a ring-like center, made of smaller centers which surround and intensify the first. The boundary also unites the center with the centers beyond it, this strengthening it further.

The fifteen properties are not independent. They overlap. In many cases we need one of them to understand the definition of another one. This is because it is the field of centers itself which is primary, not these fifteen properties. The properties are simply aspects of the field which help us to understand concretely how the field works.

However, even though the properties do not have primary significance and it is the field of centers, or the wholeness itself, which is primary, still there is an important sense in which the fifteen ways may represent an exhaustive description of all possible ways in which the field of centers works. Each of the properties describes one of the possible ways in which centers can intensify each other. Each one defines one type of spatial relationship between two or more centers, and then shows how the mutual intensification works in the framework of this relationship.

In effect, the fifteen properties are the glue, through which space is able to be unified. The fifteen properties provide the ways that centers can intensify each other. Through the intensity of centers, space becomes coherent. As it becomes coherent, it becomes alive. The fifteen properties are the "ways" it comes to life.

6. The Fifteen Properties in Nature

6. The Concept of Living Structure

Among natural phenomena, the fifteen properties seem to appear, pervasively, in almost everything. Yet among human artifacts, the fifteen properties appear only in the good ones. How can the very same properties be marks of good structure in human artifacts, and yet be present in all of nature? What is it about nature which always makes its structures "good"?

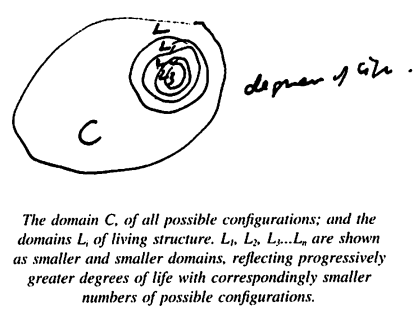

The essence of the problem is that we have not, as far as I know, every yet concentrated out attention on the fact that in nature, all the configurations that do occur belong to a relatively small subset of all the configurations that could possibly occur. It is that which permits, I believe, the characterization of a certain class of structures as living structure.

To make this more clear, consider two mathematical sets of possible configurations. First, is the domain C, which contains all possible three dimensional arrangements that might exist. It is almost unimaginably large, but nevertheless (in principle) it is a finite set of possible configurations. Second is the domain L, of all configurations which have living structure as I have defined it. L, too, is very large, but smaller than C. Just how large depends on the cutoff for structures we include as being living.

These two sets, C and L, are rather artificial. My definitions have not been precise enough to make them perfectly welldefined. Still, naming them is useful, because it allows me to say something important, that I could not say otherwise. The essence of my point is simple. It may well be that all naturally occurring configurations lie in L while, on the other hand, not all man-made configurations lie in L.

For this to be true, we merely need to show that for some reason nature, when left to its own devices, generates cofigurations in L, but that human beings are able, for some reason, to jump outside L, into the larger part of C. That is, human beings - and designers, above all - are able to be un-natural.

The sum total of all that could occur (C), is the set of all possible (imaginary and actual) configurations that might appear in the world. But nature does not create all possible configurations. In fact, what we call nature only creates things from a drastically limited set of configurations (L), which are constrainted by restrictions on the types of process that occur in nature. Essentially, nature always follow the rule that each wholeness which comes into being preserves the structure of the previous wholeness, so that all of nature is just that structure which can be created by a smooth structure-preserving process of ufolding.

That is why we see the fifteen properties throughout almost all of nature, at almost all scales. And, even though this living structure in nature is a product of natural laws, in buildings and human artifacts, which are works of imagination, these restrictions on structure-preserving processes do not necessarily apply. It is possible - very easily possible - for human designers to design unnatural structures of a kind which could not (in principle) occur in nature.

In nature the principle of unfolding wholeness (to be described in Book 2) create living structure nearly all the time. Human designers, who are not constrained by this unfolding, can violate the wholeness if they whish to, and can therefore create non-living structure as often as they choose.

The important thing to recognize is that nature - all nature -- is a living structure. This, on reflection, must lead to insights and modifications in our idea of what nature is and how it works.

7. 없음

7이 없고 6에서 바로 8로 넘어감.

8. A New View of Nature

The concept of wholeness as a structure depends on the idea that different centers have different degrees of life, and therefore on the idea that the existence of these varying degrees of life thoughout space is a fact about the world. To say that every part of nature has its wholeness, is to say that we cannot look at nature correctly without seeing distinctions of degree of life - and hence of value -- within nature itself.

...

In the new viewpoint, the harmony of nature is not something automatic, but something to be marvelled at - something to be treasured, sustained, harvested, cultivated, and sought actively. ... Although much of nature is relatively neutral, beginnings of differences in value occur within nature itself.

Once people appear on the planet, the difference becomes sharply accentuated. Most human actions are governed by concepts and visions. These may be - but may easily not be - congruent with the wholeness which exists. Under the influence of concepts, it becomes harder and harder for us to remain in harmony with the emerging wholeness. Often our actions, intentionally or unintentionally, are at odds with out own wholeness, and at odds with the wholeness of the world.

Part Two

In chapters 1~6, I have laid a foundation for order to be understood as some degree of living structure, a well-defined structure that occurs in varying degrees in buildings and in every part of space.

Now, in Part 2, I come to a second view of the same subject matter. In the next five chapters, it will turn out that order - and living structure - cannot be fully understood if we regard them merely as something in Cartesian space, a mechanism separate from ourselves. Rather it turns out that living structure is at once both structural and personal. It is related to the geometry of space and to how things work. And it is related to the human person, deeply attached to something in ourselves, even emanating perhaps from ourselves, in any case inextricably connected with what we are, who we are, how we feel ourselves to be as individuals and persons, being whose lives are ultimately based on feeling.

This revelation - and after seeing what I have to say about it you may agree, I hope, that it is a revelation - means that the nature of order as I have defined it, in principle at least can finaly bridge the gap that Alfred North Whitehead called "the bifurcation of nature". It unites the ovjective and subjective, it shows us that order as the foundation of all things (and, not so incidentally, as the foundation of all architecture, too) is both rooted in substance and rooted in feeling, is at once objective in a scientific sense, yet also substantial in the sense of poetry, in the sense of the feelings which makes us human, which make us in secret and vulnerable thoughts, just what we are.

This is, scientifically and artistically, a hopeful and amazing resolution. It means that the four-hundred-year-old split created between objective and subjective, and the separation of humanities and arts from science and technology can one day disappear as we learn to see the world in a new fashion which allows us simultaneously to be cold and hard where that is appropriate, and soft and warm where that is appropriate. It can lead to a mental world where art, form, order, and life unite our feeling with our objective sense of reality, in a synthesis which opens the door to a form of living in which we may be truly human.

Above all, this is the threshold of a new kind of objectivity.

7. The Personal Nature of Order

1. Introduction: What does it mean for something to be personal?

무언가 personal하다는 것은 if it reflects the peculiarities of a given individual이다: 당신이 오토바이를 좋아한다는 것, 이를테면; 내가 좋아하는 색깔이 녹색이라는 것 등등.

내 생각에는, 이것은 what "personal" really means에 대한 매우 협소한(shallow) 해석이다. A thing is truly personal 그것이 우리 안에 있는 우리의 인간성(humanity)을 건드릴(touch) 때. 그래서, 이를테면, this miniature sketch of a synagogue is personal. 그것은 personal하다. 왜냐하면 그것은 raises feelings of a human and personal nature in us 우리가 그것을 보았을(look at it) 때. It makes us feel vulnerable, slightly weak at the knees. It raises the childish in me. It touches me in some vulnerable part.

"personal"이라는 단어의 trivialization은 현재 우리 대중적인 문화의 일부분이다, immersed in mechanistic cosmology. 하지만 이 책에서의 world-picture의 관점에서 보면, "personal"은 a profound objective quality which inheres in something. 그것은 idiosyncrate하지 않고 universal하다. 그것은 사물(a thing) 그 자체 안에 있는 무언가 참되고(true) 기초적인(fundamental) 것을 가리킨다(refer).

I believe all works which have deep life and wholeness in them are "personal" in this sense.

센터들의 필드(the field of centers)가 참될(authentic) 때, 그것은 항상 개인적(personal)이다. 만약 그것이 올바른 구조를 가지고 있지만 개인적이 아니라면, 텅 빈 구조이고, only masquerading as life, 그리고, 모든 이러한 경우에는, it will turn out that we have misjudged it structurally. When the field of centers is authentic, it is always personal. If it appears to have the right structure but is not personal, it is empty structure, only masquerading as life - and, in every case like this, it will turn out that we have misjudged it structurally. The existence of a personal feeling in a thing or system is not a subjective quality of limited validity, but an objective quality whose existence is as foundamental to any given situation as the more mechanical facts to which we are accustomed.

2. Our Everyday Personal Feeling and The Field of Centers

To make it more clear how the field of centers and our deep personal feeling are connected, 몇몇 일상의 사례를 생각해보는 것이 유용하다.

예를 들면, 거의 모두는 꽃을 사랑한다. Few things in the world are quite as moving as a meadow full of wildflowers in early spring: buttercups, daisies, tiny orchids, forget-me-nots, wild roses, cowslips, primroses, wild hyacinths, and dozens of tiny flowers 너무 흔해서 우리가 이름을 잘 모르는 것들 - white lilies of the valley, yellow ragwort, sky-blue bluebells, scarlet primpernels. I don't know if anyone has ever asked just why flowers, of all things, should seem so so especially lovely, so beautiful to us. 하지만 wholeness라는 아이디어는 그것을 참으로 잘 설명한다. 꽃은 자연에서 일어나는, 가장 완벽한 센터들의 장(fields of centers) 중 하나이다. 그리고 꽃들이 무리지어 있을 때, on bushes, clumped, strewn in a meadow together는 highly complex living fields of centers를 만든다, perhaps among the most beautiful in nature. 만약 센터들의 장이, 그것 자체로, 우리와 깊이 연결되어 있는 것이 참이라면, and stirs our feelings, our passion, then of course a meadow full of flowers - one of the most elaborate and simple fields of centers - will have thouse touching quality we know: depth, tenderness, and loging.

같은 현상, 같은 정서적인 힘이 다른 평범한 사물들에도 존재한다. 예를 들어 생각해보라, 어린이의 생일 파테와, 그 파티의 high point, 불이 켜진 채 케잌이 방 안으로 들어오는 순간, 그리고 테이블 가운데에 자리잡고. 그 테이블은 그 자체로 LOCALLY SYMMETRICAL이다, BOUNDARY와 STRONG CENTER와 함께. 가장자리(boundary)를 더 단단하게(solid) 만들기 위해, 우리는 가장자리(edge) 주위에 put the place settings, each one itself destined to be a center. 그리고 to mart the main center, 우리는 place there a great jug of fowers, 또는 케이크 그 자체, making a GRADIENT toward the middle. 그리고, at each place settings, we put a small place mat, with the knives and forks arranged around it in symmetries to create the center more firmly, and to create detail at the boundary of this smaller center. To make the place even nicer, we will perhaps use a lace table mat, which itself has a major center and a lacy, imbricated edge, again making still smaller centers around the center.

The big jug of flowers that fills the center of the table might perhaps have two candels, one on iether side, to mark it and to form its edges. The minor center, the birthday cake itself, is also decorated with a ring of small birthday candles in ALTERNATING REPETITION, marking its boundary, forming a chain of centers, leaving the central space in the middle of the cake cmpty (THE VOID)) for the name of the person, or an ornament.

The process of producing and responding to centers is one of the most fundamental of all human processes. It is completely natural in the most ordinary way. A daisy chain, a birthday cake, a wedding ring, a bunch of flowers, the setting of a table - each of these widespread and common things is an example of the field of centers in everyday life. Each brings with it connections to an ocean of personal feeling.

Much of the concentration of feeling in a culture is placed into these vessels and others like them. It is the field of centers which reinforces the feeling in these things. It is the field of centers which thus helps give the most ordinary events their meaning.

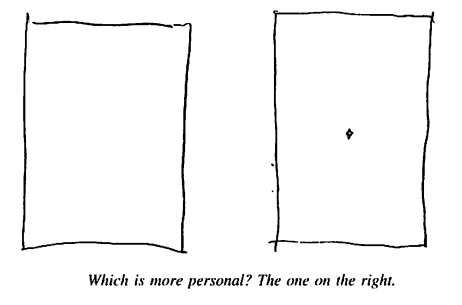

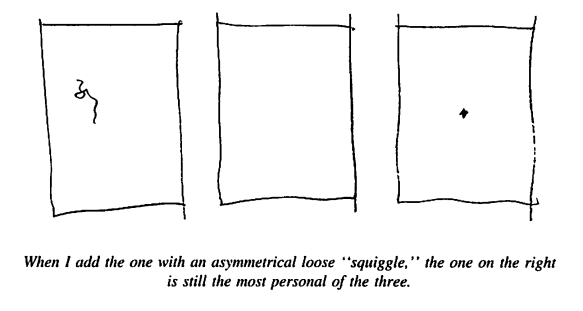

3. Wholeness and Feeling

Living structure is, by its very nature, personal and feeling-endowed. The field of centers exists in a thing to that degree to which the thing has personal feeling.

Let me explain this in terms of the field of centers. If I look at the right-hand sheet of the three, the world seems to tie itself together, it centers in on the diamond, I feel a focus or a concentrated knot in the fabric of things. This simple field of centers is coherent. In the middle sheet, I do not feel this so intensely, but still the page fits, in a reasonably calm way, into the world: there is still a coherent field of centers, so that there is still connectedness, though not as much as in the right-hand sheet. In the one on the left, there is a sense of disturbance: the squiggle interacts with the page in such a way that even the page itself no longer fits nicely into the world around it. The field of centers is incoherent, and the overall connectedness has been disturbed.

In the sense I am describing, the sheet with the diamond-shaped dot in the middle creates the most wholeness in the world. The one with the squiggle create the least. In addition, the one with the diamond has the most personal feeling, and the one with the squiggle has the least.

Why do I say that the one with the diamond has the most personal feeling in it? I can explain that by using the following experiment: suppose, as in chapter 9, I ask you tell me which of the three you would pick as a picture of your wholesome self, or your own soul. I think you will pick the right-hand one first, the middle one second, and the left-hand one third. You may agree with this, but still wonder why I call the diamond personal. It perhaps does not seem personal in the ordinary sense.

To convince you that it is indeed more personal than the others, let me propose another thought experiment. Suppose you are with a person you love very much. Imagine you are comfortable, happy, loving, and childish with this person - also vulnerable, and not afraid of being vulnerable. Perhaps you may even feel like a little five-year-old in the degree of your trust and vulnerability. And suppose you have just made the three pieces of paper we have been looking at.

Imagine now that you want simply to give one of these pieces of paper of this person as a funny, special present, as an expression of your feeling - a tiny gift, which will flutter away in the wind five minutes later, but which you want to give in such a way as to share your inner secret with this person. Which of the three will you give? Most likely, you will give the one on the right. The one with the diamond feels valuable, feels worth giving, feels the most intimate of the three.

8. The Mirror of the Self

1. Introduction

다음 장들에서는 이 관점이 내가 지금까지 강조하지 않았던 특징을 가지고 있음을 보여줄 것이다: 이것은 인간의 자아와 깊게, 그리고 필연적으로 연결되어 있다. In the next chapters, I shall show that this view has a feature which I have not emphasized so far: it is deeply, and necessarily connected to the human self.

앞으로의 장들에서, 내가 제안하는 세계관에서는 이러한 상황이 변화하는 것을 볼 수 있을 것이다. 이 새로운 세계관은 전체성과 중심의 구조를 바탕으로 하며, 외부 또는 객관적인 세계와 나의 자아 경험 간의 연결은 깊고 즉각적이다. 그것은 의미가 있다. 그것은 널리 퍼져 있다. 그것은 직접적이다. We shall see, in the following chapters, that this situation is changed in the world-picture which I propose. In this new world-picture, based on wholeness and the structure of centers, the connection between the outer or objective world and my experience of the self is profound and immediate. It makes sense. It is pervasive. It is direct.

자아와 세계관 간의 새로운 관계에 접근하기 위해, 우리는 다시 어떤 것들이 더 많은 생명을 가지고 있고 어떤 것들은 덜 가지고 있는지를 결정하는 방법에 대한 질문으로 돌아가 보자. 내가 1장부터 7장까지 설명한 것은 생명이 세상의 센터들의 존재에 전적으로 의존하는 현상으로 볼 수 있다는 것을 알려준다. 전체성(wholeness)은 센터들로 이루어진다. 센터들은 공간에 나타난다. 전체성이 깊어질수록 우리는 그것을 건물, 다른 인공물, 자연, 심지어 행동 속에서 생명으로 경험한다. 생명은 더 깊거나 덜 깊을 수 있는데, 이는 센터들이 서로 다른 생명의 정도를 가지고 있고, 하나의 센터의 생명은 다른 센터들의 생명에 의존하기 때문이다. 따라서 건물의 생명은 서로 다른 센터들이 서로를 지탱하고 협동적으로 그들의 생명을 강화하는 재귀적인 현상으로 이루어진다. 이는 건물의 기능적 생명(작동하는 방식)과 기하학적 생명(아름다움)에 대한 책임이 있다. 두 가지는 하나의 동일한 것이다. To approach the new relation between self and world-picture, let us turn again to the question of how we decide which things have more life, which has less. What I have described in chapters 1 to 7 tell us that life can be seen as a phenomenon which depends entirely on the existence of centers in the world. Wholeness is made of centers. Centers appear in space. When the wholeness becomes profound, we experience it as life, in buildings, in other artifacts, in nature, even in actions. The life is able to be more profound, or less profound, because the centers themselves have different degrees of life and the life of any one center depends on the life of other centers. The life of a building thus comes about as a recursive phenomenon in which different centers prop each other up and intensify their life cooperatively. It is responsible for the functional life in a building (the way it works) and for the geometric life (its beauty). They are one and the same thing.

... 하지만 우리가 그것을 받아들이고 싶더라도, 여전히 그것이 무엇을 의미하는지 잘 알지 못한다. 이것은 무엇인가? 공간이 생명을 얻으면서 발생하는 이 것은 무엇인가? 중심의 생명은 무엇이며, 그것이 곱해지고 피어나 건물, 장식물의 생명, 심지어 살아있는 것의 생명까지 형성하게 되는 것인가? ... But even if we want to accept it, we still don't really know what it means. What is it? What is this thing which happens as space comes to life? What is the life of a center, which then multiplies and blossoms to form the life of buildings, ornaments... and perhaps even the life of living thing?

우리는 그것을 어떻게 측정하고, 주어진 센터에 내재된 생명의 정도를 어떻게 추정할 수 있는지 알아야 하며, 무엇보다도 그것이 무엇인지 찾아내야 한다. 전체성이 보이는 만큼 중요하다면, 그것을 객관적으로 이해할 수 있어야 하고, 우리가 주목하는 세계의 어떤 부분에서 객관적으로 존재하는 것으로 인식할 수 있도록 배워야 한다는 것이 당연히 필수적이다. 비록 나는 그 존재의 객관성에 의존하는 주장을 해왔지만, 그것을 객관적으로 확립하는 데 필요한 경험적 방법을 아직 제시하지는 않았다. 즉, 논란이 있는 경우 우리가 어떻게 합의에 도달할 수 있는지를 알려주는 방법을 제시하지 않았다는 것이다. We need to know how to measure it, how to estimate the degree of life inhrent in a given center, and above all to find out what is is. If the wholeness is as important as it appears to be, it is of course essential that we can reach an objective understanding of ot, that we learn to recognize it as something which is objectively present in any given part of the world we pay attention to. Although I have made arguments which depends on the objectivity of its existence, I have not yet presented the empirical methods which are needed to establish it as objective -- which tell us how, in disputed case, we can reach agreement.

결국, 외부(객관적인) 전체성과 내부(주관적인) 자아 간의 관계와, 다양한 장소에서 생명의 정도를 확립하는 데 필요한 경험적 방법은 깊게 연결되어 있다. 이 둘은 실제로 하나의 동일한 아이디어의 두 가지 측면이 된다. 그것은 우리가 한 사물이 다른 사물보다 더 높은 생명의 정도를 가지고 있다고 보았을 때, 어떤 종류의 판단을 하고 있는가 하는 질문에 달려 있다. As it turns out, the relation of the outer (and objective) wholeness to the inner (and subjective) self, and the empirical methods needed to establish degree of life in different places, are deeply connected. They turn out, indeed, to be two facets of one and the same idea. It hinges on the question: what kind of judgment are we making when we see that one thing has greater degree of life than another?

2. Liking Something from the Heart

"좋아함"이라는 개념에서 시작해 보자. Let us start with the idea of liking.

사람들이 좋아한다는 것은 종종 신뢰할 수 없다. 왜냐하면 그것은 마음에서 우러나온 것이 아니기 때문이다. What people like can often not be trusted, because it does not come from the heart.

반면, 진정한 좋아함은 마음에서 우러나며, 사물의 생명(生命)과 깊은 연관이 있다. 마음에서 우러나서 무언가를 좋아한다는 것은 그것이 우리 자신을 더 전체적(全體性)으로 만들어준다는 뜻이다. 그것은 우리에게 치유의 효과가 있다. 그것은 우리를 더 인간답게 만든다. 심지어 우리 안의 생명(生命)까지 증가시킨다. 더 나아가, 나는 이 마음에서 우러나오는 좋아함이 세상의 진정한 구조(構造)를 인식하는 것과 연결되어 있다고 믿는다. 그것은 사물의 본질에 뿌리를 두고 있으며, 우리가 구조를 진정한 모습으로 볼 수 있는 유일한 방법이다. On the other hand, real liking, which does come from the heart, is profoundly linked to the idea of life in things. Liking something from the heart means that it makes us more whole in ourselves. It has a healing effect on us. It makes us more human. It even increases the life in us. Further, I believe that this liking from the heart is connected to perception of real structures in the world, that it goes to the very root of the way things are, and that it is the only way in which we can see structures as they really are.

우리가 이 마음에서 우러나오는 좋아함을 이해하기 시작하면, 그것에 대해 여러 가지 중요한 것들을 발견하게 될 것이다. As we begin to appreciate this liking from the heart, we shall find out a number of important things about it.

우리가 좋아하는 것(마음에서 우러나오는)은 그것들 가까이 있을 때 우리를 전체적(全體性)으로 느끼게 한다. 1. The things we like (from the heart) make us feel wholesome when we are near them.

우리는 이러한 것들을 만들 때도 전체적(全體性)으로 느낀다. 그것들을 만들뎐서, 그리고 만들고 난 후, 우리는 자신 안에서 온전함을 느끼고, 치유되며, 세상 안에서 제대로 됨을 느낀다. 2. We also feel wholesome when we are making these things. As we make them, and after making them, we feel whole in ourselves, healed, and right with the world.

이 마음에서 우러나오는 좋아함의 의미에서 우리가 진정으로 좋아하는 것에 대해 정확할수록, 우리는 다른 사람들과 이러한 것들에 대해 합의하는 것을 더 많이 발견한다. 3. The more accurate we are about what we really like, in this sense of liking from the heart, the more we find out that we agree with other people about which these things are.

우리가 마음에서 우러나서 좋아하는 것은 사물의 전체성(全體性) 또는 생명(生命)의 객관적인 구조(構造)와 일치한다. 우리가 마음에서 우러나서 좋아하는 "그것"을 알게 되면서, 이는 가장 깊은 것임을 알게 된다. 이것은 모든 판단에 적용된다. 건축물이나 예술작품에 대한 것뿐만 아니라 행동, 사람, 모든 것에 적용된다. 4. What we like from the heart coincides with the objective structure of wholeness or life in a thing. As we get to know the "it" which we like from the heart, we begin to see that this is the deepest thing there is. It applies to all judgements - not just about buildings and works of art, but also about actions, people, everything.

우리는 실제로 마음에서 우러나오는 좋아함을 발견하는 데 도움이 되는 경험적(経験的) 방법이 있다. 그럼에도 불구하고 무엇을 정말로 좋아하는지를 찾는 것은 쉽지 않으며, 그것과 연결되는 것은 결코 자동적이지 않다. 이를 이해하고 느끼기 위해서는 노력, 힘든 작업, 그리고 개인적인 깨달음이 필요하다. 깊은 좋아함을 경험하기 위해서는 의견, 개념, 자아로부터의 해방이 필요하다. 5. There is an empirical way in which we can help ourselves to find out what we really like from the heart. Nevertheless, it is not easy to find what we really like, and it is by no means automatic to be in touch with it. It takes effort, hard work, and personal enlightenment to understand it and to feel it. It requires liberation from opinions and concepts and ego to experience deep liking.

이 깊은 좋아함의 존재 이유는 신비롭고, 명백하지 않다. 이를 탐구하기 위해서는 사물의 본질을 아주 주의 깊게 살펴봐야 한다. 심지어 물질 자체의 본질을 궁극적으로 살펴봐야 한다. 그럼에도 불구하고 그 이유는 경험적이다. 우리는 어떤 것이 우리 안에서 이 깊은 좋아함을 일으킬 수 있는지를 경험적으로 판단할 수 있다. 그것은 개인적인 문제가 아니다. 6. The reasons for the existence of this deep liking are mysterious, not obvious. To plumb them we shall have to exmine the nature of things - even, ultimately, the nature of matter itself - very carefully. Nevertheless the reasons are empirical. We may determine, empirically, to what extent a thing has the ability to rouse this deep liking in us. It is not a private matter.

어떤 식으로든, 진정한 좋아함의 경험은 자아(自我)와 연관이 있다. 우리가 자신 안에서 진정한 좋아함을 일깨우는 것들을 발견할 때, 우리는 이전보다 자신과 더 만나는 느낌을 갖게 된다. 7. Somehow, the experience of real liking has to do with self. As we find out which things awaken real liking in ourselves, we find ourselves more in touch than before with our own selves.

우리가 정말로 좋아하는 것들을 발견할 때, 우리는 모든 것과 더 연결된 느낌을 갖게 된다. 8. When we find out the things we really like, we are also more in touch with all that is.

본질적인 점은 우리가 무언가를 진정으로 좋아할 때, 일반적으로 그것에 대해 합의한다는 것이다. 이는 현대적인 사고와 놀라울 정도로 다르기 때문에 매우 신중하게 논의할 필요가 있다. 이해의 주요 혁신은 우리가 일상적인 종류의 좋아함(우리가 좋아하는 것에 대해 명백히 합의하지 않는 경우)과, 내가 보여주려고 할 더 깊은 종류의 좋아함(우리는 합의한다) 을 구별할 수 있을 때 올 것이다. 궁극적으로 우리가 합의하는 이 더 깊은 종류의 좋아함이 건축의 영역에서 좋은 판단의 기초를 형성할 것이다. 나의 주장의 핵심은 이 더 깊은 종류의 좋아함이 단지 존재할 뿐만 아니라, 살아있는 구조와 객관적이며 구조적인 생명(生命)의 존재와 정확히 일치한다는 것을 보여주는 것이다. The essential thing is that, when we really like something, we generally agree on it. This is so shockingly different from modern idea that it needs to be discussed very carefully. The main breakthrough in understanding will come when we are able to distinguish the everyday kind of liking (where we obviously do not agree about what we like) from the deeper kind of liking where, as I shall try to show, we do agree. Ultimately it will be this deeper kind of liking, where we agree, that forms the basis for good judgment in the realm of architecture. The crux of my argument will be to show that the deeper kind of liking not only exists but also corresponds exactly to the presence of living structure, and to objective and structural life.

3. An Empirical Test for Comparing the Degree of Life of Different Centers

어떤 중심이 더 많은 생명(生命)을 가지고 있고, 어떤 중심이 덜 가지고 있는지를 객관적으로 결정하기 위해서는 사람들에게 주관적인 선호의 함정에서 벗어나게 하고, 대신에 그들이 느끼는 진정한 좋아함에 집중할 수 있는 실험적 방법이 필요하다. To decide objectively which centers have more life and which ones have less life, we need an experimental method that allows people to escape from the trap of subjective preference, and to concentrate instead on the real liking they feel.

이것은 어떻게 이루어질 수 있는가? 관찰자가 객체에서 생명 또는 전체성(wholeness)을 명확하게 품질로 볼 수 있도록 하고, 학습된 선호, 경험 부족, 의견, 편견의 겹침을 넘어설 수 있는 방법이 있는가? How can this be done? Is there a way of seeing life or wholeness in a building which allows the observer to see life or wholeness clearly as a quality in the object, and to rise above overlays of learned preference, inexperience, opinion, and bias?

나는 그런 방법이 있다고 믿는다. 내가 제안하는 방법은 각자가 관찰자로서 전체성(wholeness) 현상에 직접적으로 조율되어 있고, 특정한 상황에서 전체성이 존재하는 정도와 전체성 자체를 모두 볼 수 있다는 사실을 활용한다. 이 전체성에 대한 인식을 달성하기 위해, 사람들에게 자신의 감정에서 직접 나오는 판단을 요구한다. 여기서 내가 의미하는 것은 "어떤 것이 가장 좋다고 느끼는가?"라고 묻는 것이 아니다. 내가 말하고자 하는 것은, 두 가지 중에서 어떤 것이 관찰자에게 가장 wholesome한(건강한, 전체의) 감정을 일으키는지 구체적으로 묻는 것이다. I believe there is. The methods I propose make use of the fact that each one of us, as an observer, is directly tuned to the phenomenon of wholeness, and is able to see both wholeness itself and the degree to which it is present in any given situation. It accomplishes this awareness of wholeness, by asking people for a judgement which comes directly from their own feeling. I do not mean by this that we ask someone "Which one do you feel is best?" I mean that we ask, specifically, which of the two things generates, in the observer, the most wholesome feeling.

내가 제안하는 관찰 방법에서, 관찰자는 우리가 판단하려는 두 가지 중 각각이 얼마나 그 자체의 모습인지를 묻는다. 여기서 내가 의미하는 것은, 당신의 wholesome한(건강한, 전체의) 자아, 어쩌면 우리의 영원한 자아를 말하는 것이다. In the method of observation which I propose, the observer asks to what degree each of the two things we are trying to judge is, or is not, a picture of the self -- and by this I mean your and my wholesome self, perhaps even out eternal self.

가정해보자. 당신과 내가 커피숍에서 이 문제에 대해 이야기하고 있다. 나는 실험에 사용할 것을 찾기 위해 테이블을 둘러본다. 테이블 위에는 케첩 병 하나와 아마도 구식 소금 그릇 하나가 있다. 나는 당신에게 묻는다: "이 두 가지 중 어떤 것이 당신 자신의 자아와 더 비슷한가?" 물론, 이 질문은 다소 황당하게 보인다. 당신은 "합리적인 답변이 없다"고 정당하게 말할 수도 있다. 그러나 내가 질문을 고집한다면, 당신은 나를 재미있게 여기고 두 가지 중 하나를 선택하기로 동의한다고 가정해보자. 즉, 당신 자신, 즉 전체성에서 당신을 대표하는 것처럼 보이는 것을 선택하는 것이다. Suppose you and I are discussing this matter in a coffee shop. I look around on the table for things to use in an experiment. There is a bottle of ketchup on the table and, perhaps, an old fashioned salt shaker, both shown on the opposite page. I ask you: "Which one of these is more like you own self?" Of course, the question appears slightly absurd. You might legitimately say, "It has no sensible answer." But suppose I insist on the question, and you, to humor me, agree to pick one of the two: whichever one seems closer to representing you, your own self, in your totality.

당신이 선택하기 전에, 나는 몇 마디를 더 덧붙인다. 나는 두 물체 중 어떤 것이 당신의 전체를 더 잘 보여주는지, 즉 당신의 전부를 더 잘 나타내는지를 묻고 있음을 분명히 한다. 이는 당신의 모든 희망, 두려움, 약점, 영광, 그리고 황당함을 포함하여 당신이 있는 모습 그대로를 보여주는 그림이다. 이는 가능한 한 당신이 언제나 바라던 모든 것을 포함한다. 다시 말해, 당신의 약함과 인간성을 전부 포함한 진정한 당신의 모습을 보여주는 것이 무엇인지; 당신 안의 사랑과 증오, 젊음과 노화, 선과 악, 과거와 현재, 미래에 대한 모든 것을 포함한 모습은 무엇인지; 당신이 되고자 하는 것에 대한 꿈과 현재의 모습 등 모든 것을 아우르는 것이 무엇인지에 가까워지는 것을 묻는 것이다. Before you do it, I add a few more words. I make it clear that I am asking which of the two objects seems like a better picture of all of you, the whole of you: a picture which shows you as you are, with all your hopes, fears, weaknesses, glory and absurdity, and which -- as far as possible -- includes everything that you could ever hope to be. In other words, which comes closer to being a true picture of you in all your weakness and humanity; of the love in you, and the hate; of your youth and your age; of the good in you, and the bad; of your past, your present, and your future; of your dreams of what you hope to be, as well as what you are?

...

그러나 결과의 가치와 실험의 성공은 그들이 대답하는 질문에 달려 있다. 그리고 그들이 정말로 이 질문에 대답하고 있는지가 중요하다. 항상 케첩 병을 선택하는 사람들이 있다. 그들이 그렇게 선택하는 데에는 합당한 이유가 있다. 케첩은 햄버거와 함께 사용된다. 그것은 우리 현대 생활의 아이콘과도 같고, 일상적이고 편안하며, 우리의 일상생활과 연관되어 있고, 매우 식별 가능하기 때문이다. 또한 꽤 좋기도 하다. 이에 비해 소금 그릇은 거의 고대의 느낌을 준다. 많은 사람들이 여전히 이런 유형의 소금 그릇을 가지고 있지만, 그것이 우리의 생활에서 사라질 것만 같은 느낌이 드는 것은 다른 방식으로 소금을 분배하는 것으로 대체될 수 있기 때문이다. 이 모든 것은 사실이며, 이 질문을 스스로에게 하는 20%의 사람들이 케첩 병을 선택하는 이유를 설명해준다. 그러나 이 모든 것은 내가 질문하고자 하는 방식과 관련이 없다. 내가 묻고자 하는 질문은, 이 두 가지 중 어느 것이 당신의 영원한 자아와 더 깊게 연결되어 있는가? 어떤 것이 당신의 영원한 자아, 당신이 내부에 존재하는 핵심적인 열망의 더 나은 그림처럼 느껴지는가? But the value of the result and the success of the experiment depends on the question they are answering: and on whether it really is this question they are answering. There are, always, those who choose the ketchup bottle. There are good reasons why they do. Ketchup goes with hamburger. It is an icon, almost, of our modern life; we associate with it because it is ordinary, comfortable, relevant to everyday life, and highly indentifiable. Also rather nice. The salt shaker is almost archaic by compararison. Though many people still have this type of salt shaker around, it feel as though it might disappear from our lives, be replaced by another way of dispensing salt. All this is true, and explains why twenty percent of the people who ask themselves this question choose the ketchup bottle. But none of this is relevant to the way I mean the question to be asked. The question I mean to ask is, of the two, which is more deeply connected to your eternal self? Which feels as if it is a better picture of your eternal self, your aspiration, the core of you that exists inside?

...