NatureOfOrder written by ChristopherAlexander

Contents

Author's Note

Preface: Towards a New Conception of the Nature of Matter

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. The Personal

4. That Exists In Me, and Before Me, and After Me

5. Changes in Our Idea of Matter

Part One

We stand face to face with art. Can we make the eternal, simple thing, that belongs utterly to the world, and that preserves, sustains, extends, the beauty of the world?

Is this truly possible? Can it be done, in our world of trucks, freeways, computers, and prefabricated furniture and prefabricated drinks?

Throughout Books 1, 2 and 3, I have presented a veriety of propositions about living structure. They are results of observation. Many of then rely, explicitly, on unusual methods of observation. Many are based on feeling. They are capable of teaching us a new attitude towards the art of buildings. They are capable, in principle, of transforming our physical world for the better.

But, powerful and effective as these methods are, they are likely to be ignored or rejected by the reader so long as they are understood within a mechanistic world-view. A person who adheres to classical 19th - or 20th-century beliefs about the nature of matter, will not be able, fully, to accept the revisions in building practice that I have proposed, because the revisions will remain, for that person, too disturbingly inconsistent with the picture of the world. The old world-picture will constantly graw at our attempts to find a wholesome architecture, disturb our attempts, interfere with them - to such an extent that they cannot be understood or used successfully.

Unless our world-picture itself is changed and replace by a new picture, more consistent with the felt reality of life in buildings and in our surroundings, the idea of life in buildings itself (even with all its highly practical revisions in architectural practice) will not be enough to accomplish change.

1. Our Present Picture of the Universe

1. Cosmology

2. The Strength of the Present Scientific World-Picture

3. The Weakness of the Present World-Picture

따라서 우리 마음속에는 두 개의 세계가 존재합니다. 하나는 매우 복잡한 메커니즘 시스템을 통해 그려진 과학적 세계입니다. 다른 하나는 우리가 실제로 경험하는 세계입니다. 이 두 세계는 지금까지 의미 있는 방식으로 연결되지 않았습니다. 1920년경에 글을 쓴 알프레드 노스 화이트헤드는 이 현대적 문제, 즉 자연의 이분법에 주목한 최초의 철학자 중 한 명이었습니다. 화이트헤드는 우리가 스스로 경험하는 자아와 우리가 외부에서 보는 물질의 기계적인 성격이 "하나의 그림으로 통합될" 때까지 우주와 그 안에서의 우리의 위치를 제대로 이해하지 못할 것이라고 믿었습니다. 저는 이것에 동의합니다. 그리고 인간의 삶과 건축이 어떻게 관련되어 있는지를 보여주는 신뢰할 수 있는 관점은 화이트헤드의 이분법이 해소되기 전까지는 가질 수 없다고 믿습니다. 실제로 해소될 때까지는 적어도 부분적으로 우리는 스스로를 기계로 생각하지 않을 수 없습니다! There are thus two worlds in our minds. One is the scientific world which has been pictured through a highly complex system of mechanisms. The other is the world we actually experience. These two worlds, so far, have not been connected in a meaningful fashion. Alfred North Whitehead, writing about 1920, was one of the first philosophers to draw attention to this modern problem, which he called the bifurcation of nature. Whitehead believed that we will not have a proper grasp of the universe and our place in it, until the self which we experience in ourselves, and the machinelike character of matter we see outside ourselves, can be united in a single picture. I believe this. And I believe that we shall not have a credible view that shows how human life and architecture are related until Whitehead's bifurcation is dissolved. Indeed, until it is dissolved, we cannot help -- at least partially -- thinking of ourselves as machines!

4. The Needs of Architecture

(CA가 NOO 1~3권 전체에 대해 요약하는 내용)

질서의 본질 (the nature of order) 전반에 걸쳐 저는 살아있는 구조에 대한 다양한 제안을 제시했습니다. 이러한 제안은 어떤 의미에서든 관찰의 결과입니다. 저는 사물의 생명의 정도 (degree of life)에 대한 관찰을 제시했으며, 건물에서부터 콘크리트, 벽돌, 나무에 이르기까지 이 생명의 정도 (degree of life)가 놀라울 정도로 달라지는 방식을 다뤘습니다. 저는 세계의 전체성의 본질과 그것이 중심 (centers)에 의존하는 방식에 대해 언급했습니다. 또한, 생명의 정도 (degree of life)와 연관된 기하학적 속성의 정의를 제시했으며, 이는 건축물과 인공물 및 자연의 많은 부분에서 만연해 보입니다. Throughtout =THE NATURE OF ORDER= I have presented a variety of propositions about living structure. All these propositions are, in one sense or another, results of observation. I have presented observations about the degree of life in things -- even in buildings, even in concrete and brick and wood -- and the surprising way this varies. I have presented comments about the nature of wholeness in the world, and its dependence on centers. I have presented definitions of geometric properties, correlated with degree of life -- which seem pervasive in buildings and artifacts and in many parts of nature.

저는 우리 시대의 진정으로 아름다운 것을 만드는 방법을 보여주고자 했습니다. 인간의 과정과 절차적 순서가 일관된 살아있는 구조의 진화에 미치는 영향에 대한 결론을 제시했습니다. 저는 조화로운 과정과 그것이 건물 계획, 건물의 구조, 건물의 세부 기하학 및 자재로부터 건물이 어떻게 건축되는지에 미치는 영향에 대한 많은 구체적인 예를 제시했습니다. 저는 자아의 거울 (mirror of the self) 테스트와 수천 개의 중심 (centers)에서 관찰된 생명의 정도 (degree of life) 간의 명백한 상관관계에 대한 다소 놀라운 사실을 제시했습니다. 또한 인간의 감정 (feeling)이 물질 시스템의 생명 (life)과 어떻게 상관관계가 있는지에 대한 관찰을 제시했습니다. I have tried to show how to make things, in our time, which are truly beautiful. I have presented conclusions about the impact of human process and procedural sequence on the evolution of coherent living structure. I have presented examples -- many detailed examples -- of harmonious process and its impact on planning of buildings, structure of buildings, on the detailed geometry of buildings and the way a building is constructed from material. I have presented rather surprising facts about the apparent correlation of the mirror of the self test with observed life in thousands of centers. I have presented observations about the way that human feeling seems to correlate with life in material systems.

제가 제시한 아이디어는 일부는 확고하고 일부는 더 가벼운 것이지만, 우리의 과학과 기술의 일상적 경험에서 일반적인 생각과는 여러 면에서 다릅니다. 많은 아이디어는 명시적으로 비유상한 관찰 방법에 의존하고 있으며, 감정 (feeling)에 기반을 두고 있습니다. 이들은 건축 예술에 대한 새로운 태도를 가르쳐줄 수 있으며, 원칙적으로 우리의 물리적 세계를 더 나은 방향으로 변화시킬 수 있는 가능성을 가지고 있습니다. The ideas I have brought forward -- some solid, some more tentative -- are in many ways unlike the ideas that as common in our daily experience of science and technology. Many of them rely, explicitly, on unusal methods of observation. Many are based on feeling. They are capable of teaching us a new attitude towards the art of building. They are capable, in principle, of transforming our physical world for the better.

5. Scientific Efforts to Build an Improved World-Picture

우리의 세계관이 부적절하기 때문에 20세기 후반 동안 많은 과학자들이 세계관을 보완하려는 심각한 시도를 시작했습니다. 이는 전체성의 중요성과 전체에 집중된 진지한 노력의 물결이 일어났습니다. 이러한 태도는 양자 물리학, 시스템 이론, 혼돈 이론, 복잡한 적응 시스템 이론, 생물학, 유전학 및 기타 여러 출처의 융합에서 비롯되었습니다. 이들은 우주를 끊어지지 않은 전체로서의 보다 총체적인 모습으로 그리려 했습니다. 이 그림은 대중에게 널리 소개되었고, 과학자들 사이에서도 폭넓게 논의되었습니다. 이는 여러 다른 분야의 과학자들이 공동으로 이룬 대규모의 노력으로, 많은 물리학자와 생물학자들이 참여했습니다. 이들 중에는 에르빈 슈뢰딩거, 데이비드 봄, 프란시스코 바렐라, 존 벨, 유진 위그너, 로저 펜로즈, 일리야 프리고진, 베노이트 맨델브로트, 브라이언 굿윈, 존 홀랜드, 스튜어트 카우프만, 메이완 호 등이 포함됩니다. 그들의 작업의 결과로, 특히 20세기 마지막 10년 동안, 새로운 태도가 나타나기 시작했습니다. Because our world-picture is inadequate, during the second half of the 20th century many scientists began a serious attempt to repair the world- picture. There was a spate of serious effort, primarily concentrated on the importance of wholeness, and ofthe whole. This attitude came from a confluence of quantum physics, system theory, chaos theory, the theory of complex adaptive systems, biology, genetics, and other sources. It set out to paint a more holistic picture ofthe universe — a picture of the universe as an unbroken whole. The picture was widely presented to the public, and widely discussed among scientists. It was a large effort, made jointly by scientists in many different fields, many of them physicsts and biologists. They included, among others, Erwin Schrodinger, David Bohm, Fran cisco Varela, John Bell, Eugene Wigner, Roger Penrose, Ilya Prigogine, Benoit Mandelbrot, Brian Goodwin, John Holland, Stuart Kaufmann, Mae-Wan Ho. As a result of their work, especially during the last decade ofthe 20th century, a new attitude began to emerge.

이 새로운 태도는 양자역학의 결과에서 시작되었습니다. 이 결과는 국소 입자의 행동을 정확하게 묘사하기 위해 단순히 물리적 사건의 국소 구조를 바라보는 것으로는 충분하지 않으며, 어떤 강력한 방식으로 각 국소 사건의 행동은 전체에 의해 영향을 받는다고 보여주었습니다. 몇몇 경우에는 국소 사건이 전체 우주의 행동이나 구조에 영향받거나 영향을 받는다는 징후도 나타났습니다.이는 빛의 속도보다 빠르게 전파되는 영향과 상호작용을 포함합니다. 어쨌든 중요한 것은 물리적 시스템의 행동은 항상 "전체의 행동"이며, 독립적으로 행동하는 사건이 아니라는 것입니다. This new attitude began with results in quantum mechanics which showed that an accurate picture of local particle behavior, can not be reached merely by looking at the local structure of physical events; rather, that in some compelling way the behavior of each local event must be considered to be influenced by the whole. In a few cases there have even been indications that the local events are influenced by, or been subject to, behavior and structure of the universe as a whole, including influences and interactions which propagate faster than the speed of light. The vital thing, anyway, was that behavior of physical systems is always "behavior of the whole," and cannot events acting by themselves.

이러한 발전과 함께 생물학에서도 유사한 새로운 태도가 발전하고 있었습니다. 19세기와 20세기 초 과학에서는 유기체의 조정 기능에 대한 주목이 부족했습니다. 진화 과정에서 복잡한 구조의 출현과 생태 시스템의 일일 작업에서, 전체 생태계와 개별 유기체의 진화에 대한 충분한 주목이 없었습니다. 이러한 결핍은 많은 변수가 상호작용하는 복잡한 시스템이 갖는 새로운 속성, 때로는 "Emergent" 속성이라고 불리는 속성을 보여주려는 시도로 해결되었습니다. 이러한 속성은 시스템의 네트워크 성격, 변수 및 그들의 상호작용에 내재한 조직된 복잡성 때문에 단순히 발생합니다. 혼돈 이론, 복잡한 시스템 이론, 프랙탈 이론, 복잡한 시스템에서의 자아 생성 개념의 발전은 서로 연결된 시스템에서 예상치 못한 복잡한 행동이 어떻게 발생하는지를 보여주는 주목할 만한 새로운 결과를 도출했습니다. 이러한 시스템에서 거의 자발적으로 설득력 있는 질서가 발생하는 것을 보여주는 정리가 증명되었습니다. In parallel with these developments, a similar new attitude was developing in biology. In 19th-century science and in early 20th-century science there had been insufficient attention to the coordinating functions of the organism; to the appearance of complex structure in the course of evolution and in the daily working of ecological systems; to the evolution of whole ecologies and individual organisms. These deficiencies were answered by an attempt to show that complex systems, systems in which many variables interact, have new properties — some times called "emergent" properties — that arise merely because of the organized complexity in herent in the network character of the system, its variables, and their interactions. The development of chaos theory, the theory of complex systems, fractals, the idea of autopoesis in complex systems, have led to remarkable new results, which show how unexpected and complex be haviors arise in richly interconnected systems. Theorems have been proved to show how com pelling order arises, almost spontaneously, in these systems.

그리하여 생물학, 생태학, 복잡한 시스템 이론의 신흥 분야, 물리학 등이 모두 지역 시스템이 전체의 행동에 의해 영향을 받고, 그로 인해 강제된다는 새로운 세계관의 방향을 제시하기 시작했습니다. Thus biology, ecology, the emerging fields of complex systems theory, and physics, have all begun to pointtheway towards a new conception of the world in which the local system is influenced by, and compelled by, the behavior of the whole.

일부 과학 작가들은 이러한 발전이 인류와 경이로움, 자아가 포함된 미래의 새로운 세계관을 알리는 것이라고 주장했습니다. 프리트조프 카프라는 그의 저서 <물리학의 도>에서 이 관점을 표현한 최초의 인물 중 한 명이었습니다. 최근에는 20세기 후반 과학의 전통을 언급하며 생태학자인 스튜어트 카우안이 나에게 편지를 보냈고, 그 안에서 그는 이렇게 말했습니다: "과학과 신학 모두에서 의식, 영혼, 전체성, 그리고 삶이 공간-시간의 세계, 물질과 에너지, 우주 그 자체의 구조에 내재해 있다는 오랜 중요 전통이 있습니다. 이 는 신체화와 화신화의 관점으로, 수소 원자조차도 깊고 신비로운 열등성을 가지고 있으며 (타이야르 드 샤르댕의 표현), 자기가 조직하는 구조가 응집하고 소통하며, 모든규모의 수준에서 150억 년의 공동 이야기가 상호 의존을 드러내고, 깊은 생명이 우주의 본질에서 번쩍이는 관점입니다 .." Some science writers have claimed that these developments herald a future new worldvision in which humanity, and wonder, and self, are included. FritjofCapra, in THE TAO OF PHYSICS, was one of the first to express this point of view. More recently, referring to the tradition of late-20th- century science, the ecologist Stuart Cowan wrote me a letter, in which he said: "There is, in both science and theology, a long and important tradition of seeing consciousness, spirit, whole ness, and life immanent in the world of space-time, of matter and energy, of the structure of the universe itself. It is a view of embodiment and incarnation, in which even a hydrogen atom has a profound and mysterious inferiority (Teilhard de Chardin's phrase), in which self-organizing structures cohere and communicate, in which in terdependence emerges from a fifteen billion year shared story at all levels of scale, in which profound life shimmers forth from the very fabric of the universe .."

이것은 낙관적이고 긍정적입니다. 그리고 실제로 새로 전파된 지혜는 과학의 이러한 새로운 사건들에 의해 세계관이 깊이 재구성되었다고 시사하는 것처럼 보입니다. 그래서 그것은 종교의 오랜 열망까지도 포함한 완전히 새로운 그림입니다. This is optimistic and positive. And indeed, the newly propagated wisdom seems to suggest that the world-picture has been so profoundly reformulated by these new events in science, that it is a wholly new picture in which even the old aspirations of religion are encompassed.

새로운 과학적 저작들 속에서는 아름다움과 영감을 주는 생각의 구절들을 만나는 것은 분명한 사실입니다. 예를 들어, 메이완 호는 유기체 내의 활동에 대해 "어떤 사람이 상상해야 할 것은 모든 단계에서의 엄청난 활동의 벌통이며 — 전자기 스펙트럼의 73옥타브의 3분의 2 이상을 사용하여 만들어지는 음악 — 지역적으로 혼돈스럽게 보이지만, 전체로서 완벽하게 조정되어 있습니다. 이 정교한 음악은 기분과 생리의 변화에 따라 끝없는 변형으로 연주되며, 각 유기체와 종은 고유한 레퍼토리를 가지고 있습니다."라고 씁니다. It is certainly true that within these new scientific writings, one encounters passages of beauty and inspiring thought. For example, Mae-Wan Ho writes of the activity within the organism, "What one must imagine is an incredible hive of activity at every level of magnification — of music being made using more than two thirds of the 73 octaves of the electromagnetic spectrum — locally appearing as though chaotic, and yet perfectly coordinated as a whole. This exquisite music is played in endless variations subject to our changes of mood and physiology, each organism and species with its own repertoire. . ,"

이 구절은 인간적이고 아름답습니다. 그러나 이런 구절조차 자세히살펴보면 여전히 기계론적이라는 점이 남아 있습니다. 이들은 전체를 다루고 있으며, 전체의 움직임에서 경이로운 행동을 기술하고 있습니다; 작가는 태도에서 깊은 전체론을 가지고 있습니다. 하지만 그녀가 묘사하는 것은 여전히 기계적입니다. 그녀가 새로운 비전을 위해 얼마나 헌신하고, 물리학의 새로운 전체성 이해를 도입하려고 노력하더라도, 기계론적 과학의 언어는 여전히 방해가 됩니다. 전체성 자체는 실제 계산 속에서 구조로서 나타나지 않고 있습니다. The passage is humane and beautiful. Yet even such passages, when examined closely, remain mechanistic in their detail. They deal with the whole and they describe wondrous behavior in the movement of the whole; the writer is deeply holistic in her attitude. But what she describes are still mechanisms. No matter how dedicated she is to a new vision, how hard she tries to bring in the new understanding of wholeness in physics, the language of mechanistic science keeps getting in the way. The wholeness itself does not yet appear in the actual calculations as a structure.

언급된 일부 과학자들은 자연의 이분법 문제가 해결되었다고 암시하고, 아마도 그렇게 믿고 있을지도 모릅니다. 즉, 지금까지 성취된 전체에 대한 철저한 강조가 우리가 마침내 안착할 수 있는 우주의 비전을 창출할 것이라고 믿고 있습니다. 기계 같은 현상과 함께 공존하는 느껴지는 자아의 수수께끼가 복잡한 시스템의 조정 및 물리학자가 전체에 주의를 기울이는 새로운 방식의 강조에 의해 해결되었다고 믿고 있습니다. Some of the scientists referred to imply, and perhaps believe, that the problem of the bifurcation of nature has been solved; that the thoroughgoing emphasis on the whole which has been achieved will now create a vision of the universe in which we may at last be at home; that the enigma of the felt self, coexisting with the machine-like play of fields and atoms, has been resolved by the new emphasis on the coordination of complex systems and the physicist's new way of paying attention to the whole.

저는 그들의 낙관이 잘못되었다고 믿습니다. 자아와 물질 간의 분열, 즉 화이트헤드의 이분법은 오늘날에도 거의 이전과 동일하게 강하게 지속되고 있습니다. 새로운 관점과 전체의 비전이 제시됨으로써 문제는 약간 완화되었을 수도 있지만, 그러한 비전은 과학적으로 인간 자아가 자신의 자리를 찾을 수 있게 할 수 있는 형태로 아직 성취되지 않았습니다. 이러한 새로운 이론들이 명확히 전체를 다루고 있기 때문에 기계론적 어려움을 극복한 것처럼 보이지만, 과학의 이러한 사건에서 나타난 새로운 비전은 여전히 이전의 기계론적 과학을 단순히 전체에 대한 초점을 강화함으로써 개선했을 뿐입니다. I believe their optimism is misplaced. The central dilemma, the split between self and matter — Whitehead's bifurcation — continues to day almost as strongly as before. It has been alleviated, perhaps just a littie, by the prospect of a new vision and by the prospect of a vision of the whole. But that vision has not yet been achieved, scientifically, in a form which allows the human self to find its place. Because these new theories explicidy concern themselves with the whole, they appear to have overcome the mechanistic difficulties. However, the new vision which has emerged from these events in science has still only improved the earlier mechanistic science by focusing better on the whole.

"우주에서 느껴지는 '자아'의 존재, 의식의 존재, 그리고 자아와 물질 간의 생명력 있는 관계" 등은 아직 실용적이거나 과학적으로 적용 가능한 방식으로 그림에 들어오지 않았습니다. 그런 의미에서 수정된 세계관조차도 여전히 '단지' 비활성적인 것만을 다루고 있습니다. 기계론적 세계관의 가장 근본적인 문제는 아직 해결되지 않았습니다. The personal, the existence of felt "self" in the universe, the presence of consciousness, and the vital relation between self and matter -- none of these have entered the picture yet, in a practical or scientifically workable way. In that sense the world picture, even as modified, still deals only with the inert -- albeit as a whole. The most fundamental problem with the mechanistic world picture has still not -- yet -- been solved.

화이트헤드의 균열은 여전히 남아 있습니다. Whitehead's rift remains.

6. The Continuing Lack of a Unifying Cosmology

7. Ten Tacit Assumptions Which Underlie Our Present Picture of the Universe

8. Inspiration for a Future Physics

9. The Confrontation of Art and Science

10. A Fusion of Self and Matter

2. Clues From the History of Art

1. Introduction

2. An Observation

3. Relatedness

4. A Possible Explanation

5. A Connection to the Self

6. What of Out Modern Works?

7. More on the Problem of our Era

8. The Black Plater

9. Footnote

3. The Existence of an "I"

나는 모든 건축이 관계성에 의존한다고 믿는다. 잘 작동하는 건물은 사람과 우주 사이에 관계성을 만드는 건물이다. I Belive that all architecture depends on relatedness. Those buildings which work are the ones which create relatedness between a person and the universe.

1. A Dewdrop

나는 당신이 춥고 맑은 날씨에 이슬방울 중 하나를 바라보면서 자신과 이슬방울 사이에 어떤 관계성을 느낀다고 믿는다. 그것은 아름답다, 맞다. 하지만 당신이 느끼는 것은 그 이상이라고 생각한다. 당신은 그것과 관련되어 있다고 느낀다. I believe that you, looking at one of these dewdrops in the cold weather, feel some relatedness between yourself and the dewdrop. It is beautiful, yes. But what you feel goes beyond that, I think. You feel related to it.

하지만 나는 더 나아가야 한다고 주장하고 싶다. 당신과 이슬 방울 사이에 실제로 관계성을 경험하도록 말이다. 마치 당신의 영혼, 당신의 존재, 그리고 이슬방울이 얽혀서 서로 관련되어 있는 것처럼. But I want to insist that it goes further, that you experience an actual relatedness, between you and the dewdrops, as if your eternal soul, your existence, and the drops, are entangled, related to each other.

내가 말하고자 하는 것은 당신의 일상적인 자아가 이슬방울과 정확하게 관련되어 있다는 것이 아니다. 내가 제안하는 것은, 마치 당신의 영원한 자아, 당신 안의 영원한 부분이 이슬방울과 관련되어 있는 것과 같다. 마치 그것이 이슬방울 속에 존재하는 듯한 느낌이다. 당신은 그런 무언가를 느낀다. I do not mean to say that it is your daily self, exactly, that is related to the drops. It is more, I suggest, as if your eternal self, the eternal part of you, is related to the drops. Almost as if it exists as a presence in the drops. You feel something like that.

2. Relatedness

만약 내가 정원에 있는 전통적인 오래된 벤치를 본다면, 나는 그것과 관련되어 있다고 느낀다. 만약 내가 오래된 자연스럽게 부서진 나무 그루터기를 본다면, 나는 그것과 관련되어 있다고 느낀다. 하지만 내가 강철 창문이나 컴퓨터 케이스를 본다면, 나는 그것들과 덜 관련되어 있다고 느낀다. If I look at a traditional old bench in the garden, I feel related to it. If I look at an old naturally broken tree stump, I feel related to it. If I look at a steel window or at a computer casing I feel less related to them.

고대 세계의 건물과 물체 또한, 사람들이 그것을 바라보면 그와 관련되어 있다고 느끼도록 만들어졌다. 오늘날, 만약 내가 최근 시대의 아파트 건물이나 큰 슈퍼마켓의 주차장을 본다면, 나는 이러한 것들과 덜 관련되어 있다고 느낀다. 그것들은 비어 있는 것처럼 보인다. 현대 시대의 시작은 우리가 관련되지 않는 수많은 구성들로 가득한 세상을 만들었다. The buildings and objects of the ancient world, too, were usually made so that if people looked at them they felt related to them. Today, if I look at an apartment building of recent times, or at the parking lot of a big supermarket, I feel less related to these things. They seem vacant. The onset of the modern era has created a world full of configurations to which we do not reel related.

3. The Mirror-of-the-Self Experiments

1권에서 나는 우리가 상당히 일관된 결과를 가지고 우리 자신의 모습에 더 가까운 구성과 덜 가까운 구성을 구별할 수 있음을 보여주었다. (나의 실험은 일반적이었지만, 특히 다양한 인공물과 예술 작품에 대한 인식에 집중하였다.) 서로 다른 구성들을 비교할 때, 우리는 어떤 것이 우리 자신의 모습의 그림과 더 비슷한지, 어떤 것이 덜 비슷한지를 보고, 말하고, 결정할 수 있다. In Book 1, I have shown that we are able to distinguish, with rather consistent results, configurations that are more and less like our own selves (my experiments were general, but focused especially on the perception of various artifacts and works of art). When comparing different configurations, we can see, tell, and decide which of them is more like a picture of our own self, and which is less.

가장 중요한 점은 우리가 두 가지를 비교하고 "두 가지 중 어느 것이 내 영원한 자아에 더 가깝거나 덜 가까운가?"라는 질문에 집중할 때, 서로 다른 인간들이 상당 부분 동의한다는 사실이다. 이 결과는 실험적으로 검증할 수 있다. 실험에 대한 몇 가지 중요한 측면이 있다: Most important is the fact that when we compare two things and concentrate on the question "Which of the two is more or less like my eternal self?" we find that different human beings agree, to a significant extent. This result is experimentally verifiable. There are further aspects of the experiments which are significant:

매우 높은 정도로, 사람들은 결과에 대해 동의한다. 즉, 같은 문화에서 온 사람들은 영원한 자아를 구체화하는 것으로 같은 것들을 선택하는 경향이 있다. 더 놀랍게도, 서로 다른 문화의 사람들조차도 전반적으로 동의하며, 그들의 영원한 자아의 그림으로 같은 것들을 선택한다. To a very large degree, people agree about the results. That is, people from the same culture tend to choose the same things as embodying the eternal self. More remarkably still, even people from different cultures agree, on the whole, and choose the same things as pictures of their eternal self.

사람들은 때때로 이 실험에 참여하는 것에 대해 불안해하는데, 그들은 자신이 받고 있는 질문이 "의미가 있는지" 궁금해하기 때문이다. 최상의 결과를 얻기 위해, 나는 실험의 피험자에게 "물론, 이것은 아무 의미가 없다. 걱정하지 마라, 이것은 그냥 게임이다; 물론 의미가 없다, 그런 것들을 다 잊고 질문에 답해보도록 해라. 그냥 나를 웃겨주기 위해서 해줘, 만약 당신이 '어느 하나'를 당신의 영원한 자아의 그림으로 선택해야 한다면, 어떤 것을 선택할 것인가?"라고 말하는 것이 보통 필요하다는 것을 알게 되었다. 사람들이 실험을 그저 재미로 하게 되면, 우리는 일관된 결과를 얻는다. 그러나 나는 곧 항상 사람들이 불안해하는 이유는 현재의 우주론의 "공식 버전"이 질문이 의미가 있도록 하지 않기 때문이라고 생각해왔다. 그 결과, 사람들은 어떻게 그것을 바라보거나 생각해야 할지 모르는데, 비록 그들의 감정이 그것이 의미가 있다고 알려 준다 해도, 질문에 답하려고 하는 순간에 더욱 그렇다. People are sometimes uneasy about participating in this experiment, because they wonder if the questions they are being asked "make sense." In order to get the best results, I usually found it necessary to tell the subject of the experiment, "Of course, it does not mean anything. Don't worry, this is just a game; of course it doesn't make sense, just forget all that and try to answer the question. Please just do it to humor me, just tell me, if you had to choose one or the other as a picture of your eternal self, then which one would you choose?" Once people do the experiment, just for the hell of it, we get consistent results. But, it has always seemed to me that people are uneasy because the "official version" of current cosmology does not allow the question to make sense. As a result, people do not know how to regard it or think about it, even if their feelings tell them that it does make sense, once they try to answer it.

사람들이 이러한 기준을 사용할 때, 예술 작품에 대한 판단은 상당한 정도로 정보가 있는 판단과 일치하는 경향이 있다. 따라서 이 기준을 사용함으로써 사람들은 "아름다움은 보는 사람의 눈에 있다"는 예술에 대한 관점을 초월할 수 있는 어떤 원천이나 정보의 출처를 발견하게 되며, 대신 시각 예술의 다양한 분야에서 전문가들이 내리는 판단과 유사한 정보에 기반한 판단을 내릴 수 있게 된다. The judgments people make about works of art, when using this criterion, tend to coincide in considerable degree with informed judgements about art. Thus by using this criterion, people find in themselves some wellspring or source of information which allows them to supercede the "beauty is in the eye of the beholder" view of art, and instead allow them to make informed judgments similiar to the judgments made by experts in different fields of the visual arts.

이 세 번째 결과는 실험의 중요성을 강조하고, 그것이 깊은 내용을 가지고 있음을 분명히 한다. 나는 이 실험을 원래 1970년대 어느 시점에 학생들이 "좋아함"과 예술적 판단이 주관적이라는 생각을 넘어설 수 있도록 돕기 위한 방법으로 고안하였다. 이를 통해 학생들이 사물, 객체, 인공물, 건물 등의 품질에 대한 일관되고 신뢰할 수 있는 판단에 도달할 수 있는 방법을 제공하고자 하였다. This third result raises the importance of the experiment, strikingly, and makes it clear that it has a profound content. I invented the experiment, originally, at some time in the 1970s, as a way of helping students get beyond the idea that "liking" and artistic judgement are subjective, and to give them a way of reaching consistent and reliable judgment about the quality of things, objects, artifacts, buildings, and so on.

내가 처음 세 권의 책에서 살아 있는 구조(living structure)에 대해 설명한 것은 여기서 분명한 역할을 한다. 나무와 구름 그리고 찻잔은 강철 컴퓨터 케이싱보다 더 많은 살아 있는 구조를 가지고 있다. 그것은 살아 있는 중심들의 구조가 그들에게서 더 발달했음을 의미하며; 이러한 구조들을 생성한 과정은 접힘(unfolding) 과정이었고, 더 생물학적 성격을 가지며, 더 자연스러웠다. 그들은 더 많은 생명을 가지고 있다. 컴퓨터 케이싱은 생명이 더 적다. My description of living structure in the first three books has an obvious role here. The tree and the cloud and the tea bowl have more living structure than the steel computer casing. That means that the structure of living centers is more developed in them; and the process which generated these structures was an unfolding process, more biological in character, more natural. They have more life. The computer casing has less life.

그러므로, 나, 살아 있는 존재로서, 내 주변에 살아 있는 구조를 가진 것들에 더 큰 친화력을 느끼고, 살아 있는 구조가 부족한 것들에는 더 적은 친화력을 느낀다고 말하는 것이 분명해 보인다. 이런 이유로 (사람들이 말할 법하듯이) 당연히 나는 이 페이지에 나온 찻잔이나 전통적인 노르웨이 오두막에 더 관련되어 있다고 느끼며, 고속도로 다리와 슈퍼마켓 주차장의 더 낯선 구조보다는 더 그렇다. It would seem obvious, then, to say that I, who am alive, feel a greater affinity for the things around me which have living structure, and less affinity for those which lack living structure. For this reason (one would expect to say) of course I feel more related to the tea bowl or to the carved traditional Norwegian hut shown on this page, than to the more alien structure of the freeway bridge and supermarket parking lot.

나는 Book 1에서, 우리가 이 살아 있는 구조들과 우리 자신 사이에 느끼는 연결을 경험적 기초 위에 두었다. Book 1에서 보고된 실험에서, 나는 우리 자신과 물건들 사이의 이 연결이 존재한다는 것을 실험적으로 확립했다. 다른 정도의 살아 있는 구조를 가진 다양한 나무나 다른 화병이 우리에게 나타나는 정도가 우리 자신의 모습의 그림처럼 비슷하게 보인다는 것을 확립했다. 그것이 우리의 인상이다. 이 인상의 존재는 경험적으로 검증 가능하다. I have, in Book 1, also put the connection we feel between these living structures and our own self on an empirical basis. In the experiments reported in Book 1, I have established experimentally that this connection of our own self to things, exists. I have established that different trees, or different vases, to the extent that they have living structure in different degree, do appear to us in comparable degree, as pictures of our own self. That is our impression. The existence of this impression is empirically verifiable.

따라서, '영원한 자아(the eternal self)'라는 것이 있을 것 같다. 실험을 글자 그대로 받아들이고, 내용에 대한 넓은 합의에 초점을 맞춘다면, 결과를 표현하는 한 가지 방법은 인류의 '깊은 자아(the deep self)'에 닮은 구성을 찾을 수 있다는 결론을 내리는 것이다. 정말로 '영원한 자아'라는 것이 존재한다는 것이 놀랍다. It would therefore seem that there is such a thing as the deep or eternal self. If we take the experiments literally, focusing on the wide agreement on the content, onw way to express the results is to conclude that it is possible to find configurations which resemble the deep self of humanity. It seems astonishing that there really is such a thing as the eternal self.

4. The Real Relatedness Existing Underneath the Skin

내가 세상의 것들과의 연관성을 강화하는 것이 "인간으로서 내 존재의 가장 근본적이고 생생한 방식"이라고 주장한다. 이러한 연관성이 발생할 때, 나 자신 -- 내가 세상과 얼마나 연결되어 있는지, 모든 물질의 내면에 있는 "무언가"에 얼마나 참여하는지의 정도는 그 때 영예롭게, 정점에 이르러, 나는 진정한 나 자신을 경험한다. 우주의 자식, 모든 것과 분리되지 않고 일부인 존재: 더 크고 무한한 자아의 작은 연장선이다. I claim that the relatedness between myself and a things in the world which encourages my relatedness is the most fundamental, most vivid way in which I exist as a human being. When it occurs, my own self -- the degree to which I am connected to the world, the degree in which I partake of the interior "something" that underlies all matter -- is then glorified, it at its zenith, and I then experience myself, as I truly am, a child of the universe, a creature which is undivided and a part of everything: a small extension of a greater and infinite self.

따라서, 나는 이 간단한 관계, 즉 연못 옆 나무그루터기와 내 자신 사이의 관계가 나를 움직이는 연결은 그 자체로 내가 우주에서 완전히 존재하는 것을 견고하게 하고, 드러내며, 그 존재를 전체적으로 포착한다는 것을 주장한다. 이것은 작은 순간이 아니다. 내가 자연의 존재나 마찬가지로 생명 구조(living structure)를 가지고 있어 나와 이런 유대를 형성할 수 있는 다른 인간이 만든 구조물의 존재를 느낄 수 있는 한, 내 존재의 영광이다 -- 내가 얼마나 겸손하든 상관없이. I claim, therefore, that this simple relation between myself and the treestump by the pond, which moves me, is a connection so profound that my full existence in the universe is made solid, is manifested, is captured by it in its entirety. It is not a small moment. It is the glory of my existence as a person -- no matter how humble I am -- which I can feel so long as I am in the presence of nature or in the presence of other human-made structures which, too, have the same living structure and hence the capacity to form this bond with me.

...

그러므로 우리의 건물이 이러한 품질을 가지고 있는지 여부 -- 그들 자신이 이 내면의 관계를 가지고 있는지 --는 가장 중요한 문제다. 내가 옳다면, 우리가 지은 세계에 있는 생명 구조의 존재가 지구와의 우리의 연관성의 정도를 결정한다. 생명 구조가 없는 건물들은 우리가 그들을 통해 연관성을 느낄 수 있는 능력을 파괴할 뿐만 아니라, 어떤 방식으로든 연관성을 전반적으로느낄 수 있는 우리의 능력을 억제하고, 줄인다. --그렇지 않으면 자연스럽게 느낄 수 있는 자연의 장소에서조차도. So whether our building have this quiality or not -- whether they themselves have this interior relation with the I -- is of the greatest importance. If I am right, it is the presence of living structure in our built world that decides the extent of our relatedness with earth. Buildings which lack living structure not only destroy our ability to feel relatedness through them. They also inhibit, somehow, and reduce the ability we have to feel relatedness at all, even in nature -- places where we would otherwise feel it naturally.

5. The Ancient and Eternal Truth of the Relatedness

인류학자들 사이에서는, 원시 사회의 사람들이 자연과 더 포괄적인 관계를 가졌으며, 우리가 하지 않는 방식으로 자연의 일부분이라고 느꼈으며, 자신들의 자아가 자연과 서로 얽혀 있다는 것을 이해했다는 것이 널리 받아들여지고, 자주 쓰여졌다. Among anthropologists, it is widely accepted, and has been writen about often, that the people in primitive societies had a more all-encompassing relationship with nature; felt themselves to be part of nature in a way that we do not; and understood that there was, or is, an intermingling of their own selves, with nature.

...

그러나 나는 이것이 실제로 사실이라고 제안한다. 사람과 세상의 살아 있는 구조(living structure) 사이의 관계는 우리가 아직 이해하지 못한 종류의 '실제적인' 그리고 '구체적인' 관계다. 이 모든 경우의 본질은 사람들이 정말로 자연 전체를 하나의 포괄적인 전체성(wholeness)으로 보았고, 그들은 그 일부였다. 이 전체와의 신성한 관계는 그들의 삶의 기초였다. 나는 그것이 그들과 그것 -- 우리와 그것 -- 이 분리될 수 없고, 분리되어서는 안 된다는 인식에 달려 있다고 생각한다. 우리는 하나의 전체의 두 반쪽이다. However, I am proposing that this is literally true. That the relation between a person, and the living structure in the world, is an actual and tangible relationship of a kind that we have not yet grasped. The essence common to all these cases, is that people really saw all of nature as a single embracing whold, of which they were a part. Their sacred relationship to this whole was the foundation of their lives. It hinged, I think, on the awareness that they and it -- we and it -- are not separated, cannot be separate, are two halves of a single whole.

6. The Numinous Experience

이러한 진술 뒤에 있는 경험을 검증하는 방법 중 하나는 실험을 하는 것이다. 내가 세상을 걸어 다닐 때, 나는 각 물건, 각 자동차 펜더, 컵과 접시가 놓인 각 테이블, 각 덤불, 피프스 애비뉴의 군중, 각 배치 등을 바라보며, 그것이 '그것'을 얼마나 가지고 있는지 스스로에게 묻는다. 여기서 '그것'은 내가 그것과 얼마나 관계가 느껴지는지, 그것이 나와의 관계를 얼마나 형성하는지, 나에게 얼마나 감동을 주는지, 그리고 그것 안에서 나와 영원한 것 사이의 관계를 어떻게 구현하는지를 의미한다. 무엇보다도, 끊임없이 드는 질문은 이렇다: "나는 그것과 얼마나 개인적인 관계를 느끼고 있는가? 그것은 내가 꿈과 슬픔, 세상의 아름다움을 볼 수 있는 풀장 역할을 얼마나 하고 있는가?" A way to verify the experience behind these statements is by doing experiments. As I walk about the world, I can look at each thing, each car fender, each table with its cups and saucers, each bush, each knot of people on Fifth Aenue, each configuration, and ask myself to what extent it has "it" -- by that I mean, to what extent I feel related to it, and to what extent it forms this relatedness with me, to what degree it touches me, and appears to embody a relatedness between me and the eternal, in it. Above all, the question, again and again, is this: To what extent do I feel a personal relationship with it? To what extent does it serve as a pool in which I can see my dreams, sorrows, the beauty of the world?

이것은 특별한 마음가짐이다. 우리는 울타리에 설정된 한 돌을 바라보며, 다른 돌에 비해 더 많은 특성을 가진다. 페인트가 벗겨지고 석고가 부서진 벽의 한 부분은 이러한 품질을 갖추고 있다. 또 다른 벽은 새롭게 스투코 처리되고 균일한 색상을 가졌지만, 그 특성이 훨씬 적다. 또 다른 벽은 벗겨지고 부서져서 단순히 좋지 않은 모습일 뿐, 이러한 품질이 없다. It is an unusual frame of mind. We look at one stone set against the hedge and it has this element to a greater extent than another. One patch of wall with peeling paint and broken plaster has this quality. Another wall, freshly struccoed, and of uniform color, has it far less. Another wall, peeling and broken, merely looks crummy: it does not have this quality.

기본 가정은 세상에는 우리 자신의 존재와 더 깊은 관계를 갖는 장소가 있고, 덜 갖는 장소가 있다는 것이다. 원주율은 숲 속이나 언덕의 특정 지점을 신성하게 여겼다. 우리는 이를 비현실적인 것이라 경시해왔다. 그러나 내가 취하고 있는 관점에서 볼 때, 이것은 전혀 비현실적이지 않다. 이것은 내가 1에서 3권에서 설명한 것과 일치하며, 경험적으로 검증할 수 있는 사실이다. 세상에는 우리 자신의 존재와 깊은 관계를 가지는 곳이 있다. The base assumption is that there are places in the world which have more of this relation with our own selves, and there are places that have less. The primitive spoke of certain spots in the forest, or on the hills, which were sacred. We have dismissed this as something fanciful. But, from the perspective I am taking, it is not fanciful at all. It is just fact, consistent with what i have described in Book 1 to 3, and empirically verifiable. Some places in the world carry the relationship with our own selves more deeply than others.

과거 인류는 이러한 장소를 신성하게 인식해왔다. 이들은 정신을 간직한 장소다. 이들은 영혼을 간직한 장소다. 그런 언어는 유용할 수도 있고 그렇지 않을 수도 있다. 그러나 내가 강조하고 싶은 단 한 가지는: 일부 장소, 일부 사물은 우리가 더욱 강하게 관련성을 느끼게 하는 성격을 가지고 있다는 것이다. 우리는 그것, 그 장소와의 직접적인 관계를 느끼고, 우리가 모든 것, 우주와 연결되어 있다고 느낀다. Human beings have, in the past, recognized such places as numinous. They are places which carry the spirit. They are places which carry the soul. That language may or may not be useful. But what I want to insist on, is only the one thing: some places, some things, are of such a nature that we feel more intesely related to them, we feel a relationship with them, a direct relationship between our own self and that thing, that place. We feel it most strongly, and when we feel it we feel that we are connected with all things, with the universe.

이것이 내가 여기서 설명하는 모든 것의 기초가 되는 경험이다. That is the core experience which underlies everything that I am describing here.

1권의 언어에서 볼 때, 세상의 전체성은 서로의 존재에 의해 유도된 각 센터의 거대한 시스템으로 볼 수 있다. 이 센터 중 일부는 일시적이다(연못의 물결 또는 빔 속의 힘); 일부는 보기 어렵다(점이 있는 종이에서 유도된 센터); 일부는 건물의 기능에 정상적이지만 숨겨진 구조에서만 보인다(거실을 구성하는 센터); 다른 것은 명확하고, 가시적이며 구별된다(테이블, 의자, 집, 사람, 자동차, 벤치 및 나무). In the language of Book 1, the wholeness of the world may be seen as a vast system of centers, each one induced by the existence of others. Some of these centers are transitory (ripples in a pond or forces in a beam); some are hard to see (the centers induced in the sheet of paper with a dot); some are normal to the functions in a building but only visible in the hidden structure (the centers that make up a living room); others are clear, tangible, and distinct (tables, chairs, houses, people, cars, benches and trees).

이 생명 구조의 관점에서, 존재하는 각 센터는 자신의 생명 정도를 가진다. 다시 말해, 그것은 "센터로서" 존재감이 더 많거나 적다. 강한 생명을 가진 센터 내에서 구성 센터들도 또한 강한 생명을 가진다. In this view of living structure, each center which exists has its owne degree of life. Otherwise stated, it has more or less existence "as a center". Within those centers which have intense life the component centers themselves also have intense life.

특정 센터가 중심성과 생명의 강도를 가질수록, 그것은 '나'나 '너'와 더 유사해진다. 생명 강도가 높은 건물에서, 건물 자체가 센터로서 이 품질을 가질 뿐만 아니라, 그 안에 존재하는 모든 센터 및 세상에 유도된 모든 센터는 '모두' 자아의 그림이라는 속성을 가진다. The more deeply a particular center has its centeredness or intensity of life, the more it resembles me or you. In a building which has great intensity of life, not only the building itself seen as a center has this quality, but all the centers which exist within it and all the centers it induces in the world, all of them have this property of being pictures of self.

이 아이디어가 만든 비전은 단일 건물의 본질뿐만 아니라 전체 세계의 본질을 포괄한다. 꽃밭, 강, 갯벌 — 동일한 원칙이 적용된다. 중요한 것은 직물의 연속성과 생명이다. 이러한 것들 각각은 최대한 강렬한 중심의 영역을 갖는 한, 살아 있을 것이다. 그러한 세계는 우리 자신과 거의 완벽한 관계를 가질 것이다. 강렬한 중심의 영역을 가진 모든 것은 또한 인간의 자아의 그림이기 때문에, 우리가 만나는 모든 개별 부분은 어딘지 모르게 영혼의 그림이 된다. 이러한 자기 같은 성격은 널리 퍼지며, 통일성을 생성한다. 그것은 위안이 되는 세계이다. 또한 근본적인 의미에서, 정상적인 세계이기도 하다. The vision created by this idea not only covers the nature of a single building, but of the whole world. Flowerbeds, rivers, mudflats — the same rules apply. The continuity and life of the fabric is what counts. Each of these things will be alive, ot the extent that it, and each one of the others, has its field of centers as intense as possible. Such a world wil have an almost perfect relation to ourselves. Since everything with an intense field of centers is also a picture of the human self, it is a world in which every single part we encounter is somehow a picture of the soul. The self-like character which si pervasive, produces unity. It is a comforting world. It si also, in a fundamental sense, a normal world.

이런 종류의 세계는 인류 역사에서 많은 문화 속에 존재해왔다. 전통 사회에서는 거의 모든 장소, 거의 모든 세계의 부분이 강렬한 중심의 영역을 가지고 있었다. 거의 모든 도어 노브, 난간, 창문, 의자, 계단, 방, 거리, 건물, 지붕, 덤블, 나무 기둥, 보도, 문틀, 그리고 출입구는 인간의 자아의 그림으로 경험될 수 있었다. 그런 세계에서 어디를 가든, 어디를 보든, 모든 규모에서 당신은 자신을 인식했고, familiar한 것으로 사물을 보고 그들과 관계가 있다고 느꼈다. 이 세계는 친근한 세계였다. 물리적 위험에 있어서 자주 두렵게 느껴지기도 했지만, 그 모든 부분은 인간의 얼굴처럼 생동감이 있었다. 나는 그것의 각 부분과 동일시할 수 있다. 비록 많은 부분이 시간과 장소, 문명적으로 나와 멀리 떨어진 사람들에 의해 만들어졌지만, 여전히 그 안에서 내 얼굴을 볼 수 있는 놀라운 것들이 있다. 각 부분은 깊이 나와 닮아 있다. This is the kind of world which existed in many cultures for much of human history. In traditional society nearly every place, nearly every part of the world, contained an intense field of centers. Nearly every doorknob, handrail, window, chair, step, room, street, building, roof, bush, tree bole, walkway, doorpost, and doorway could eb experienced as a picture of the human self. Wherever you went ni such aworld, wherever you looked, at every scale, you recognized yourself, you saw things as familiar and felt related to them. This world was friendly. Though often frightening ni its physical dangers, every part of it was animated, like a human face. I can identify with each part of it. Even though many of them were made by people remote from me in time and place and civilization, still, the remark- ablethingsithatIsemyfaceni eachofthem. Each of them deeply resembles me.

이제 최근 수십 년간 일반화된 다른 유형의 세계와 비교해보자. 이 세계에서는 살아있는 중심들이 사물이나 장소에서 훨씬 더 드물게 존재한다. 대부분의 건물과 인공물의 구조는 그들이 포함하는 중심의 영역이 약하게 되어 있다. 그들은 인간의 자아의 그림으로 느껴질 수 있는 경우가 매우 드물다. 맥도날드의 식탁보는 좋은 예다. 그런 식탁보처럼 전체적으로, 어디에나 비인격적인 인공물들이 있다. 그들은 뒤에 이미지가 있을 수 있지만, 진정한 인류는 없다. 플라스틱 시트, 어두운 유리의 반짝이는 시트, 인위적인 패턴으로 쌓인 벽돌, 강철 몰드의 반사만 있는 콘크리트, 이상한 형태의 기둥, 제대로 되지 않은 아치. 이 두 번째 세계의 사물들 -- 도어 노브, 난간, 문, 창문, 건물, 지붕, 거리 --을 만날 때, 대다수는 자아의 거울 구조를 갖지 않고 "실패"한다. Now compare another kind of world, the world that has become common in the last few decades. In this world living centers exist far more rarely in objects or in places. The structure of most buildings and artifacts is such that the field of centers they contain is weak. Only very rarely can they be felt as pictures of the human self. The placemat at a McDonald's is a good example. Like that placemat, altogether, everywhere, there are impersonal artifacts. They may have images behind them, but no real humanity. Plastic sheets, shiny sheets of dark glass, brickwork laid in artificial patterns, concrete which only reflects the steel pans of the forms, columns in unusual shapes, arches which are not quite right. As you meet the things in this second world -- doorknobs, handrails, doors, windows, buildings, roofs, streets -- the great jamority fail to have the structure of the mirror of the self.

사물들은 차갑고, 외계적이며, 멀고, 무관해 보인다. 당신은 두렵고, 단절되며, 마음이 없다. 이 세계는 불친절한 세계다. 당신과 관련된 것이 거의 없고, 인류처럼 보이지 않는다. 당신은 당신의 자리가 없다.당신은 소속되지 않는다. Things seem chilling, alien, distant, unrelated. You feel frightened, disconnected, without heart. This world is an unfriendly world. Litle is related ot you, little seems human. You have no place. You do not belong.

이 두 세계의 차이는 — 우리가 그것을 받아들였지만 — "어마어마하다." 최근에 건설된 세계는 종종 추상적이며 — 보기에 눈이 있는 이들에게는 깊은 두려움을 자아낸다 — 전통 세계와 비교할 때. 끔찍하다. 비어있다. 버려졌다. 사람들이 이 두 번째 종류의 세계에서 미쳐버리는 것에 대한 기대가 과하다고 할 수 있을까? 하지만 이것이 오늘날 대다수 인간이 살고 있는 현실이다. The difference between these two worlds -- though we have accepted it -- is staggering. The recently constructed world is often abstract -- and for those who have eyes to see, deeply frightening -- by comparison with the traditional world. Terrible. Empty. Deserted. Is it too much ot expect that men and women may become insane in this second kind of world? Yet this is the reality of the conditions under which agreat majority of human beings live today.

두 세계는 물리적으로만 다른 것이 아니다. 그들은 또한 두 가지 다른 우주의 이미지를 전달한다... 두 가지 다른 우주론, 두 가지 다른 우주 개념의 이미지. 하나는 우주가 친근한 세계이다 — 인간과 연관되어 있으며 — 우리가 우주와 연결된 세계이다. 다른 하나는 우주가 불친절하고, 외계적이며, 우리가 그것과 연결되지 않은 세계이다. The two worlds are not only physically different. They also communicate images of two different kinds of universe ... images of two different cosmologies, two different conceptions of the universe. One is a world in which the universe si friendly -- human-related -- and ni which we are related to the universe. The other is a world in which the universe is unfriendly, alien, and we are unrelated to it.

살아있는 구조가 있을 때, 그것은 나와 너, 모든 사람과 관련이 있다. 당신은 주변을 바라보고, 당신이 자신을 보는 것들을 본다; 그것은 놀랍고, 매혹적이다. 그것은 가장 기본적인 경험이다. 어떤 다른 경험도 그만큼 위안이 되지 않는다. 그것은 "살아있는 구조"라는 문구가 암시하는 것 이상이다. 길, 나무, 석양은 나와 관련이 있다. 그것들은 어떤 자기 같은 존재의 존재를 포함한다. 모든 것이, 올바른 구조를 가질 때, 부인할 수 없이 당신과 관련이 있다. 그것은 당신과 관련이 있다: 정도의 문제이지만, 정도는 주요 문제는 아니다. 주요 문제는 관계의 "사실"이다. 우리는 하나의 것을 다른 것보다 더 사랑한다. When there is living structure, it is related to me, to you, to every person. You look out, around you, and you see things in which you see yourself; it is astonishing, absorbing. It is the most fundamental experience. No other experience is as comforting. It is beyond what the phrase "living structure" suggests. Path, tree, sunset, are related to me. They contain a presence, the presence of some I-like thing. All of it, when it has the right structure, is undeniably related to you. It is related to YOU: A matter of degree, but the degree is not the main issue. The main issue is the fact of the relationship. We love on thing more than another.

깊은 생명이 있는 세계에서는, 그 세계가 온전한 구조를 가질 때 그것은 나의 것처럼 느껴진다. 그것은 외계적이거나 죽은 것이 된다. 그것이 비인격적인 구조, 추상적인 구조로 만들어질 때, 자기 같은 특성이 더 이상 존재하지 않을 때 그렇다. In a world which has deep life, the world belongs to me, and feels like mine, when it has a structure of wholeness, deeply within it. It becomes alien, or dead, when it is made of impersonal structures, abstract structures, and when self-like qualities are no longer present.

7. True Meaning of Relatedness

이제 우리가 살아있는 물질과 느끼는 관련성의 본질에 대해 더 깊이 탐구해 보자: 우리 자신의 자아가 모든 살아있는 물질과 연결되어 있다고 느끼는것. 내가 야생 오리가 연못에서 날아가는 것을 보고 그 날갯짓 소리를 들을 때, 나는 그것이 나에게 닿는다는 감각으로 가득 차게 된다. 그것은 나와 관련이 있다. 이는 내가 빈약하게 보이는 현대 아파트 건물을 봤을 때 경험하는 느낌과는 완전히 다르다. 현대식 아파트 건물에서 느끼는 것은, 내 친구 중 한 사람이 표현했듯이, "집에 아무도 없는 것 같다"는 느낌이다. Let us now probe more deeply into the nature of the relatedness we feel with living matter: our feeling that we, in our own selves, are connected to all living material. When I see the wild duck fly off the pond and hear the beating of itw wings, I am filled with a sensation that it touches me. It has to do with me. It is related to me. This is entirely different from the feeling I experience when I see the modern apartment building with gaping windows, which strikes me as vacuous. In the supermodern apartment building, as one of my friends put it, "it seems that there is no one home".

그렇다면, 살아있지 않은 인공물에서 느끼는 공허한 느낌과 살아있는 인공물이나 자연과의 관련감을 느끼는 사이의 차이는 무엇일까? What, then, is the distinction between the vacuous feeling we get from one not-living artefact and the feeling of relatedness we experience with a living artefact or with nature?

나는 살아있는 구조를 가진 사물에서 우리가 경험하는 관련성이 심리적 속임수나 환상이 아니라는 것에 점차 확신하게 되었다. 우리가 연결로 경험하는 것은, 내가 확신하는 바로는, 실제이다. 내가 세상에서 보는 것 같은 자아 같은 존재 — 기둥의 괄호, 나무의 그루터기, 연못의 물, 흘러가는 구름 속에서 — 는 사물 안의 실제적인 것이다. 그것은 정신적 구성물이 아니다. 그것은 우리가 마음속에 형성한 아이디어가 아니다. 그것은 물질적인 사물 그 자체 안에 존재하는 실제적인 존재이다. 내가 그 연못과 나의 관계를 경험할 때, 내가 이 사물을 보고 그 안에서 나 자신을 인식할 때, 나는 그 사물과 관련되어 있다. 나는 그것을 인식하고, 그것과 관계가 있다고 느끼는데, 이는 — 어떤 방식으로든 — 내가 같은 물질로 만들어져 있기 때문이다. 내가 그것에서 경험하는 자아 같은 특성은 나에게서도 자아 같은 것으로 경험되는 것이다. I have slowly become certain that the relatedness we experience in things with living structure is not a psychological trick or an illusion. What we experience as a link is, I am certain, real. The apparently self-like presence which I seem to see in the world -- in the column bracket, in the tree stmp, in the water of the pond, in the scudding clouds -- is an actual thing in the thing. It is not a mental construct. It is not an idea we have formed in our minds. It is an actual presence in the material thing itself. When I experience the relationship of my self to that pond, when I see this thing and recognize myself in it, I am related to that thing. I recognize it, and feel related to it, because -- some-how -- I am of the same substance. The self-like quality I experience in it is what I also experience as self-like in me.

무엇보다도, 나와 그것 사이의 관련성 — 나와 나무, 나와 연못, 나와 해안에 놓인 뒤집힌 배, 나와 햇살이 비치는 창턱, 또는 비가 내리는 경우 — 는 진정한 관계이다. 이것은 나와 그것 사이에 존재하는 연결로, 중요한 것이며, 아이디어가 아니라 실제 물질적인 연결이다. 이것은 우리가 같은원자로 만들어졌다는 사실과 비슷하지만, 더 위대한 것이다. 그것은 우리가 같은 자아로 만들어졌고, 같은 내면의 특성을 공유하며, 나 자신으로서 경험하는 '나'와 그들 속에서 사랑이나 관련감으로 경험하는 '나'가 같다는 것이다. Above all, the relatedness I feel between me and it -- I with the tree, I with the pond, I with the upturned boat on the sea shore, I with the window sill as the sun gleams on it, or as the rain falls -- is a real relationship. It is a connection between me and it which exists, which is important, which is not an idea but an actual material connection. It is something like the fact that we are made of the same atoms, they and I, but it is a far greater thing. It is that we are both made of the same Self, we share the same inner character, the I which I experience in me as myself, and the I which I experience in them, as a feeling of love or relatedness.

50페이지의 이슬 방울로 돌아가 보자. 만약 당신과 이슬 방울 사이에 그런 관계가 있다면, 그것은 무엇 때문에 발생하는 것일까? 나는 현대 물리학이나 생물학의 어느 부분도 이 문제를 밝힐 수 있다고 생각하지 않는다. 그러나 만약 이 관련성이 실제로 존재한다면 — 문자 그대로 존재하며, 환상이 아닌 사실로 — 그것은 설명될 필요가 있다. Go back to the dewdrops on page 50. If there is such a thing, such a feeling of relatedness between you and the dewdrops, what might it be caused by? I do not know of any part of contemporary physics or biology which sheds light on this. Yet if this relatedness is there -- literally there, not as an illusion, but as a fact -- it needs to be explained.

...

예제를 좀 더 확장해 보겠다. 여기 중세 채색화가 있다. 앞쪽에는 푸른 언덕과 노란 꽃들이 그려져 있고, 멀리에는 반짝이는 안개와 빛나는 하늘색의 언덕이 있다. 이제 이 현상을 어떻게 경험할 수 있을지를 조금 더 자세히 설명해 보겠다. 예를 들어, 당신이 이 그림을 바라보고 있다고 상상해보자. 다시 말해, 그림 속 작은 푸른 언덕과 직접적인 관계를 느낀다고 하자. Let me expand the example a little bit. Look at the medieval illumination shown here. There is a painting of hills, green in front, yellow blossoms, in the distance a shining haze and a brilliant light blue, azure hill. Now, let me describe, in a little more detail, how you might experience this phenomenon. I imagine, for example, that you are looking at this painting. Again (let us say) you feel a direct relationship with this small piercing blue hill in the picture.

이렇게 발생하는 관련성은 당신과 그림 속 푸른 언덕 사이의 무언가이다. 당신은 푸른 부분을 마치 자신인 것처럼 경험하지는 않을 것이라고 생각한다. 오히려 당신은 자신과 푸른 언덕 사이에 무언가가 늘어나며, 그 무언가가 당신의 자아를 동원하고, 푸른 부분 향해 뻗어 나가고, 연결된다고 경험할 것이다. 여기서 작용하는 것은 바로 당신이 서 있는 자리와 푸른 언덕 사이에 늘어나는 무언가이다. 이것이 내가 언급하고 있는 관계이다. This relatedness that occurs is something between you and the bit of blue in the painting. You do not, I think, experience the bit of blue as if it were your self. I believe rather, that you experience something stretching between yourself and the blue hill, something that seems to mobilize your self, stretch it out towards the bit of blue, connect with it. The thing which comes into play, is the something stretching between you as you stand there, and the bit of blue. That is the relationship I am referring to.

무슨 일이 일어나는가? 당신은 푸른 언덕을 바라보고, 그 사이에 당신과 푸른 언덕을 연결하는 무언가가 존재하게 된다. 그러나 매우 중요한 것이 존재하게 된다. 그것은 동시대의, 일상적인 자아가 동원되는 것이 아니라, 마치 당신의 영원한 부분, 당신의 영원한 자아가 어떤 식으로 동원된 것 같고, 단지 그 푸른 부분을 바라보기 때문에 그런 일이 발생하는 것이다. What happens? You look at the blue hill and something, stretching between you and the blue hill, then comes into existence. But it is a very important thing that comes into existence. It is not the mundane, everyday self, which is being mobilized. It is as if the eternal you, the eternal part of you, your eternal self, is somehow being mobilized -- and has been mobilized -- simply because you are looking at that bit of blue.

8. A Jump to Speaking About the Existence of an "I"

나무(혹은 물방울, 혹은 파란 얼룩)에 대한 연관성을 느끼는 이 느낌 속에서, 우리 각자가 더 많거나 적게 같은 방식으로 이를 느끼기 때문에, 나무 안에 무언가 -- 실제로 존재하는 무언가 -- 있어야 한다. 이 "무언가"는 이름이 필요하다. 연관성은 고대의 무언가로, 많은 세대의 인간들이 경험해온 것이라고 믿는다. 그러나 현대에는 이것에 대해 이야기하는 것이 매우 드물고, 너무나 강하게 반대되는 경향이 있기 때문에 현대적인 용어로는 거의 언급할 수조차 없다. 우리는 더 이상 이를 위한 단어가 없고, 그 관계 자체에 대한 단어도, 내가 연관성을 느끼는 "것"에 대한 단어도 단 하나도 가지고 있지 않다. Within this feeling of relatedness with the tree (or the dewdrop or the patch of blue), and because each one of us feels it more or less the same way, there must be something -- an actual something -- in the tree. This "something" need a name. Although the relatedness is something ancient -- something experienced, I believe, by many generations of human beings -- in our time it is so unusual even to talk about it, it runs against the grain so strongly, that it can hardly even be referred to in modern parlance, because we no longer have the words for it, we no longer even have a single word for it: neither for the relationship itself, nor for the "thing" to which I feel related.

우리는 그것을 단순히 '생명 구조(living structure)'라고 부를 수 있다. 이전에 있었던 것들을 통해 생명 구조가 존재한다는 것을 알기 때문이다. 그러나 이것은 나의 경험과 그 관계에 동반되는 신비로운 감각을 전달하는 데 실패한다. 무엇보다도 나는 나무와의 연관성을 개인적으로 느낀다. 이것은 나와 관련이 있다. 나는 나무와 연관되어 있다고 느끼고, 나무와의 연결을 경험하면서 내 존재가 자라고, 확장되며, 완전히 좋은 존재가 되는 것을 느낀다. 그래서 '생명 구조' 같은 표현은 너무 추상적이다. 비록 나무 안에 실제로 생명 구조가 존재하지만, 그 표현만으로는 개인적인 연관성의 감정을 표현하거나 담기에 충분하지 않다. We could call it simply living structure since we know, from what has gone before, that living structure is there. But this fails to communicate the numinous sense that accompanies my experience of it, and my experience of the relationship. Above all, I feel the experience of relatedness with the tree as personal. It has to do with ME. I feel related to the tree, I feel that my own existence grows, extends, and becomes wholly good, as I experience my connection with the tree. So a phrase like "living structure" is far too abstract. Though there is indeed living structure that lies in the tree, that phrase alone does not express -- nor does it suffice to contain -- the personal feeling of relatedness.

경험 안에는 나에게 가장 개인적인 것에 가깝고, 훨씬 더 개인적인 무언가가 있다. 그래서 그 "것"이 존재한다면, 그 "것"은 특별한 특징을 가져야 한다. Inside the experience, there is something much more personal, almost the most personal thing there is to me. So the "thing", if thing there is, must have unusual features.

9. An Experiment to Determine the Extension of the I

An experiment: this shows a little of the way our relatedness to the world appears in us, and something of its quality.

Then I asked him, "Where does your own I stop?" Pressing him about the physical extension of the I he experienced, I asked, "When you look at the grey-brown cushion, where exactly is your I, where is your experience of I?" He indicated his own body, his head, his body, and said, "It is in here." I nodded.

So, I asked again, "Where is your I, exactly, in this case, when you are looking at the red cushion?" Remarkably, then, he said to me, "It seems to go out toward the cushio. Somehow, for some reason, I feel my I exists beyond my body, it includes the cushion ... or (he corrected himself), at least it goes out toward the cushion; when i look at the red cushion my I seems larger than before, and it tends to expand toward the cushion, includes it."

I too felt the same. So here we had a very primitive experience, which indicates the I as being larger than our own bodies, experienced in this instance as being outside our bodies occupying the space between our bodies and the thing we were looking at -- apprently because of the more I-like nature of the second cushion. It appeared that a substance like the red cushion, because more deeply connected to the I, will actually expand the experience of I in us, make our connection to a larger "something" more plainly visible.

10. The I of Our Experience Originating with the I in Things

11. A Hypothesis

이러한 주장들은 근본적으로 나에게 하나의 결론으로 이어진다: '우주에 존재하는 "나 같은 존재감(I-like presence)"이 실제로 존재하며, 사물의 체계와 물질의 구조, 우주가 행동하는 방식에서 실제적인 역할을 한다'는 것이다. 좀 더 자세히 말하자면, 나는 이렇게 결론 내렸다: 살아 있는 중심(living center)의 궁극적인 본성과 이 "나(I)"의 본성 사이에는 어떤 관계가 있어야만 한다. At root, these assertions leads, in my mind, to one conclusion: that the "I-like presence in the universe" is real, is somehow a real thing, and plays a real role in the scheme of things, and in the structure of matter, in the way the universe behaves. In slightly more detail, I have myself concluded this: There must be some relation between the ultimate nature of a living center, and the nature of this "I".

나는 책 4의 서문을 "모든 위대한 예술은 사물에서 나(I)의 형성에 달려 있다"라는 진술로 시작했다. 사물에서 그것들을 생동감 있게 하는 어떤 존재와 우리의 관계는 또한 그들이 우리와 관련이 있다고 느끼게 만든다. 하지만 '나(I)'의 주제와 우리가 그것을 인식하는 것은 그보다 더 깊은 것이다. 왜냐하면 우리의 경험의 일환으로, '나(I)'는 자연에서도 나타나기 때문이다. 그것은 세계의 모든 사물과의 관계에 영향을 미친다. I began the preface to Book 4 with the statement that all great art hinges on the formation of the I in things. The relation of ourselves with some presence in things that animates them also makes them feel related to us. But the subject of the I, and our perception of it, is deeper than that. For, as part of our experience, the I appears in nature, too. It touches our relation with all the things in the world.-

identification.

... but that in some fashion I am the waterfall: not merely identification, but actual identity. In this case, when I see the waterfall and feel related to it, I experience the relationship as more fundamental, not merely "I feel identified with this waterfall," but something more like "There is some kind of an identity between my self, and the waterfall. My I is really in the waterfall. My self and the waterfall are not merely similar, but it feels as if they are the same, as if both are parts of one thing."

Here we began to enter metaphysics.

12. Mobilizing the Storm

이제 나는 왜 건물에서의 삶과 그 삶을 만드는 과정에 대한 사실들을 이해하려면, 세상의 살아 있는 중심(living centers)과 내가 '나(I)'의 존재감(presence of the I)이라고 부르는 것 사이의 관계를 명확히 인식해야 한다고 믿는지 분명해졌다고 생각한다. 나는 세상에서의 중심성(centeredness)과 이 '나(I)' 사이의 연결의 어떤 강한 형태가 존재해야 한다고 확신한다. 이 연결이 얼마나 멀리 가는지는 잘 모르겠지만, 건물의 삶을 이해하기 위해서는 내가 이전 섹션에서 분석한 관련성의 정도(degrees of relatedness)가 내가 설명한 더 높은 강도의 수준과 비교할 수 있어야 한다는 것처럼 보인다. 그것들은 초월적인 용어로 표현될 필요는 없다. 그러나 최소한 그것들은 인간 경험의 핵심(core of human experience)으로 인정받아야 한다. ~-It is perhaps clear, now, why I do not believe that one can make sense of the facts surrounding life in buildings, or of the process of makine this life, without explicit recognition of this relationship between the living centers in the world, and what I call the presence of the I. I am certain that some fairly strong version of the connection between centeredness in the world and this "I" must exist. I am not sure just how far this connection goes, but it seems to me that to make sense of the life of buildings, degrees of relatedness, as I have analyzed them in the previous section, need to be comparable to the higher levels of intensity I have described. They do not need to be expressed in transcendental terms. But, at the very least, they must be acknowledged as a core of human experience.

When we succeed in making a living thing from this point of view, we achieve a building (ornament, painting, garden, street) in which strong centers are connected to our own (individual and collective) eternal self. That is, the center becomes something so close to us emotionally that we experience a yearning for it and belonging from it and from being in its presence. It is tied to us, as if by blood. It is ours. We shine in its presence. Such a building endows us with knowledge of ourselves, makes us feel awake, conscious, more human, more ourselves, and in the end makes us experience ourselves as if dissolved in a flood of tears.

The success of every truly great work -- town, street, buildig, painting, windowsill -- lies simply in the extent to which the living I appears in it. For every artist, every builder, this must be true: as I work I must try to create a structure which appears like I to me. I must try to arrange the colors in a painting in such a way that living breathing I appears in it. This effor makes the centers live; it makes me communicate with the ultimate beyond all things; and at the very same time it mobilizes myself, animates me, makes my person, my being, awaken, because I am then more present. It is this mobilizing of myself in the great work which chills me, devastrates ma, wakes me to the bone.And this, which is so personal because it reaches the personal in me, also connects me to the great ultimate beyond all things: to the ocean and the whild and the fire.

....

그것이 닿는 것은 이성(reason) 너머에 있고, 이성이 시작되기 전의 것이다. 그것은 내가 더 이상 존재하지 않는 어떤 영역과의 연결일 수 있으며, 내가 항상 존재할 곳이다. What it touches is beyond reason, and before reason. It may be a connection to some realm, where I no longer am, and where I shall always be.

그것이 우리가 사물의 제작자(maker)로서 맡은 임무이다: 이 '눈(eye)'을 폭풍(storm)에게 열고 동원하는 것이다. That is our task, as makers of things: to mobilize - to open - this eye to the storm.

4. The Ten Thousand Beings

1. Introduction

이제 '나(I)'에 대한 개념을 바탕으로 한 모델을 고려해보자. 이 모델에서 나는 앞서 설명한 대로 살아 있는 구조(living structure)를 중심의 시스템으로 간주하며, 각 중심은 서로 다른 정도의 생명력(life)을 가진다. 이 모델은 책 1에서 제시된 모델과 유사하며, 특히 3장과 4장에서 설명된 것과 비슷하다. 그러나 나는 이제 하나의 매우 중요한 변화를 도입한다. 시스템의 모든 중심은 어느 정도 '자아(self)'의 그림(picture)이라는 사실도 포함시키자. Let us now consider a model that builds on the conception of I. In this model, I consider living structure as I have before, as a system of centers, each center having some different degree of life. The model is similar to the one presented in Book 1, especially as it is presented in chapters 3 and 4. But I now introduce one very important change. Let us also include the fact that every center in the system of centers is, to some degree, a picture of the self.

... In some degree, all the centers are related to self. In Book 1, we spoke of the degree of life which different centers have. This is a structural matter. We now add the idea that each center has a degree of quality, an intensity of life according to the degree in which it is a picture of the self.

This model is consistent with two propositions which were introduced in Book 1: (1) that every living structure contains thousands of living centers, and (2) that every living center may be distinguished as living, to the degree that it is a picture of the eternal self. But, in Book 1, I did not go on to draw the conclusion that comes from these two propositions.

When we put these two propositions together, we can hardly avoid reaching the conclusion that every living structure is composed of thousands of pictures of the eternal self. In this model, a living structure, is not merely composed of thousands, or millions, of interacting centers. It is, equally, composed of millions of interacting pictures of the "I."

2. Consider the Possibility of Viewing All Living Centers as Being

Essentially, then, we are now viewing a living center from a new point of view. It is related to the self.

If we reexamine these examples from the point of view I have proposed, we begin to see that the recursion may be said, then, to create a being-like connection to the I. Each living center is, to some extent, an I-like picture of the self. The more life a given living center has, the more I-like it is: the more it is a picture of the self. As centers are built, strengthened, and toughened, the larger structures which contain them then, too, become more I-like. In short, the recursion, which allows us to build living structure in the world, not only makes living centers more and more strong. It also causes the appearance, somehow, of pictures of the self, throughout every nook and cranny of a region of space.

3. The Jewel Net of Indra

The model is not entirely new. In traditional Buddhism, there is a vision of the world considered as a ten thousand pictures of the self. It occurs in a fascinating but relatively unknown branch of Buddhism known as Hua-Yen. According to this vision, the world is seen as ten thousand raindrops, each an eye, each reflecting all ten thousand others.

(화엄? 이 부분은 인드라망에 대한 소개임.)

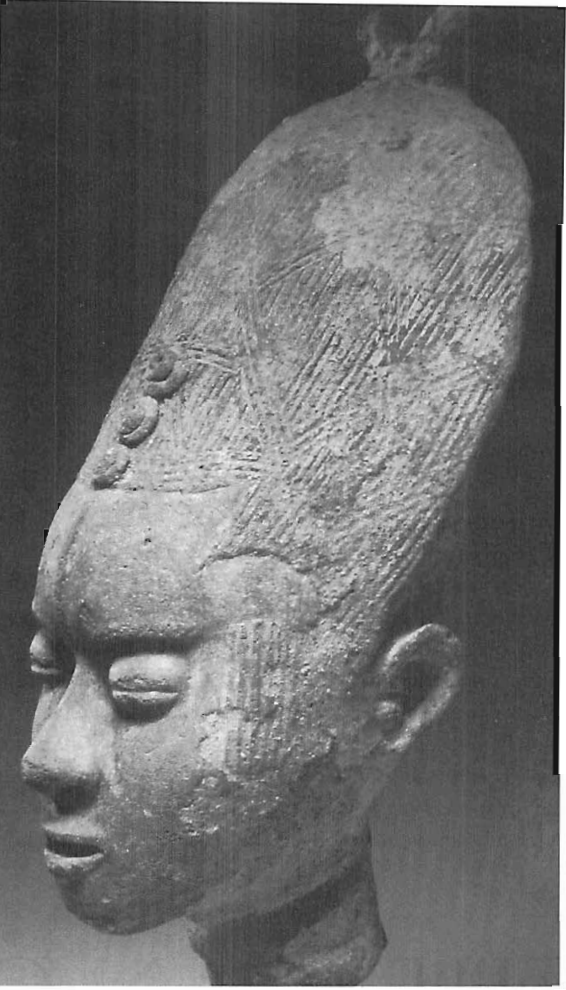

4. What it Means for a Center to be Being-Like

Look at the African head of the next page. If I speak only of my experience, I can say that the I really is in there. I am related to it, and to every part of it. Each part of it is made to be like the I, reveals the I. If you are in doubt, for contrast look at the diskette cover shown on page 78: a graphic design from about 1985. There I cannot so easily enter into its parts, I am not related to the parts, my self finds no home in them. I am not as strongly related to it, or to every part of it.

What exactly do these statements mean? To answer the question, of course, I can start by asking the reader to repeat the mirror-of-the-self experiments described in Book 1, chapters 8 and 9, laboriously, piece by piece, going through five centers in the diskette cover, comparing them with five centers from the African head.

Look at just the eyelids of the African head, their slightly bulbous swelling. Ask of this thing, "Do I feel related to it?" I answer "Yes, I do." Is that eyelid a being? Yes. Is the eyelid a picture of my self? Certainly a better picture than the inside of the diskette's capital "C."

Look at the space inside the "C" of the word "certified". It is a rounded rectangle, with a keyhole shape where it passes out into the space beyond. If I ask whether I find myself in this black bit of space, I may hesitate, be unsure. Is it a being? Is it a good picture of my self? Obviously it is not very strong. Certainly not as strong as the eyelid of the mask, or as a strand of its hair, or the slit between the eyelid and the eye.

Let us try again. Consider the space inside the bars of the capital "E" on the diskette cover. Is this a picture of myself? Do I love it, feel related to it? Again I have to answer "No." How about the bar of the E: Is this a picture of myself? No, it is nothing. Subtly, it makes me feel nothing.

...

Do you think that this is happening because the statue is a head? Look instead then, at this type from a book, (page 78): a few letters on a page, entirely abstract, formed of nothing but black and white and space, just like the diskette cover. But what a difference! Here, again and again throughout the piece of paper, I find myself related to the serifs, to the space between bars of the E, to the triangular space between the great letter G and A, to the inner triangle of the large A, to the space between the G and the smaller T which it contains, to every letters and around the letters.

Look carefully at the space inside the small "o" of the text. At a distance you think it is a circle. When you look closely, you see a beautiful, subtle, egg-shaped form sloped to the left, inside the black of the type. This shape, the egg itself, gently sloping, makes me related to it; I feel myself in it, just as with the crude shape inside of C of the diskette I feel unrelated. The feeling of relatedness -- the being-character -- lies in the geometry. It is in the space.

In case you think the computer diskette is too negative, too close to being a strawman, let us consider another artifact from our time; a pair of scissors used for haircutting. The scissors are rather beautiful and have abundant life -- but not because they are symmetrical. Leave prejudice aside, and do the mirror test. You will, I think, feel some connection to the pair of scissors, an inner connection between this pair of scissors and yourself. It is somewhat I-like. It is a being. And its interior centers are, each of them, also being-like. When we take them on by one, each is I-like, each is being-like, each is a being in its own right. It speaks to us, it evokes our cognizance of its being nature as we encouter it, use it, and look at it. And that is, indeed, exactly what we find. When we examine the internal entities within the scissors, the thumbhole of the handle, the bolt that makes the pivot, the chamfet on the blade, the point, the fleshy shaped piece of metal between bolt and handle, the cross section of the steel that forms the handle -- in every case, the smaller center is again being-like, is a mirror of the self.

To be an I-like center, a center must also be composed of centers which are themselves I-like. To be a being-like center, a center must also be composed of centers which are themselves being-like. Beings can only be made of beings. If it is not made of beings, it cannot be a being.

살아있는 중심의 I-같은 특성은 매우 중요하다. 이것은 모든 것의 핵심이다. 그러나 독자가 쉽게 동의하는 듯 고개를 끄덕이는 것은 간단할 수 있지만, 그것을 단순히 터무니없는 것으로 치부하기도 쉬울 수 있다. 실제로 그것을 이해하고, 소화하고, 경험하는 것은 어렵다. 지각, 배려, 그리고 자신의 감정과 연결되려는 의지가 필요하다. 또한, 이런 구조가 공간에 나타나도록 집중하고 노력을 기울여야 한다. 일상적으로 이러한 I-같은 구조를 만드는 operational willingness가 필요하다. 자신에게 명확하다고 말하기는 쉽지만, 그 지적인 이해를 일상적인 operational willingness로 변환하여, 당신이 만드는 건물이나 다른 것의 광범위한 구조 속 모든 중심에서 이러한 I-같은 구조를 만들어내는 것은 매우 어렵다. The I-like character of living centers is crucial; it is at the core of everything. And yet, although it could be easy for the reader to nod agreement, and could also be easy to dismiss it out of hand as absurd, actually to understand it, to grasp it, to experience it, is hard. It takes perception, care, and a willingness to be connected with your own feelings. And it takes concentration and effort to make such a structure appear in space. It requires, too, an operational willingness. It is easy enough to say to oneself that it is clear: but immensely hard to transform that intellectual understanding, into a daily operational willingness to make this I-like structure appear, in every center, throughout the vast fabric of a building or something else which you are making.

이런 이유로, 이 장의 예가 어떤 방식으로든 반복적이라면 너그럽게 용서해주길 바란다. 나는 주장을 계속하고 예시를 반복하는데, 여러 해에 걸쳐 가르쳤던 경험을 통해, 사람이 이 이해에 도달하는 데 얼마나 오랜 시간이 걸리는지를 너무 잘 알고 있다. 결국 이 이해가 완전히 흡수되고, 친숙해지며, 정말로 이해될 때까지 걸리는 시간을 말하는 것이다. 그래서 그것은 거의 제2의 본성이 된다. For this reason, I beg your indulgence if the examples of this chapter are in any way repetitive. I go on and on with the argument and with examples, because after years of teaching I know, only too well, how long it takes for a person to reach a point where this understanding is throughly assimilated, familiar, and understood so that it is really understood, and almost second nature.

5. A Corner of a Farmer's Field

6. A Shipyard

The fact that the early great industrial places had enormous life was recognized by many, including Le Corbusier. Since we can be nearly certain that these places were not created by conscious religious intent, and only by practical business-like intensity, we need to ask what process created these things, successfully making I-like centers in them, that nevertheless fails so often today when building modern warehouses, airports and so on, and fails when architects self-consciously try to use an "industrial aestetic." This is the core of the intellectual problem I have addressed in Book 2. The industrial process of the early 20th century was an unfolding process in its straightforward directness. But the post-industrial processes of the late 20th century have been contaminated by images, and no longer have the directness of real-world creation and unfolding needed to make life.

확실한 것은 건축가와 엔지니어에 의해 만들어진 이 기계들이 실용적인 목적을 위해 만들어졌다는 점이다. 우리가 살아있는 센터들의 구조에서 볼 수 있는 것은 그들의 실용성이 구현된 모습이다. 그 안에서 보이는 다양한 생활 중심은 바로 그 실용적 성격 때문에 생겨난 것이다. 이것이 그들의 실용적 효율성을 발생시키고 유지한 원인이다. What is certain is that these machines, made by builders and engineers, were made for practical ends. It is their practiality we see made flesh in the structure of living centers. The manifold living centers we see in them arise because of their practical nature. That is what caused and sustained their practical effectiveness.

7. Looking at Chartres

샤르트르 대 성당.

이제 거의 완전히 I-like 중심들로 구성된 건물을 살펴보자. 그 장소, 그 건물은 다수의 -- 정말로 환상적인 다수의 -- 수백만 개의 살아있는 중심들의 집합이다. 모든 중심은 "I"의 그림처럼 작업되고, 정립되고, 형성되었다. 어디에나 존재하는 살아있는 중심들은 그곳에서 일어나는 거의 유일한 것이다. Let us now look at a building which is composed nearly completely of I-like centers. ... Theo show that place, that building, is a multitude -- truly a fantastic multitide -- of million upon millions of living centers, all worked through, established, shaped, as pictures of the "I". Living centers, existing everywhere, are virtually the only things that happen there.

8. Each Living Center is a Being

In each case I experience each of these centers as something nearly sentient. I experience the feeling in the thing, not only in me, as I look at this being, contemplate it, meet it, confront it. Thus, literally, as I look at the catheral, which is made of a hundred million beings, I see and feel life in everything. That is the measure of its unity and greatness as a whole.

9. Pure Unity

깊이 있는 살아있는 사물에서, 그곳에 있는 생명은 단순히 다수의 중심으로 존재하는 것이 아니다. 우리는 샤르트르의 예를 통해, 그러한 사물에 특별한 특성이 존재할 수 있다는 것을 서서히 깨닫기 시작한다. 그것은 질적인 사실로, 재귀(recursion)가 점점 더 강해짐에 따라 이 사물이 점점 더 깊게 그리고 더 많이 나와 접촉하게 된다는 것이다. 그리고 동시에, 그것은 더 통일된다. 구조가 모든 중심에서 I에 접근함에 따라, 전체로서 하나의 통일성에 도달하기 시작한다. In a profoundly living thing, the life which is there is not only present as a multiplicity of centers, in recursion. With the example of Chartres, we begin to see that there may be a special quality of such a thing, that the qualitative fact that may come into being, as the recursion becomes more and more intense, is that this thing gradually and more and more deeply, makes contact with the I. And, at the same time, it becomes more unified. As the structure approaches I in every center, then as a whole, it begins to reach a single unity.

살아있는 구조는 통일적이다. 그것이 바로 생명의 목표인 통일성이다. 그것은 살아있는 구조에 의해 창조된 통일성이다. Living structure is unified. It is that unity which is the aim of life. It is the unity which is created by living structure.

어쩌면 무엇보다도 우리는 항상 살아있는 중심이 생명체이며, 존재임은 더 큰 전체에서의 위치에 따라 결정된다는 것을 기억해야 한다. 그것은 반드시 더 큰 전체에 도움을 주어야 한다. 그리고 만약 그것이 존재라면, 그것은 내부, 측면, 그리고 먼 곳에 있는 더 작은 전체로부터 도움을 받는다. Perhaps above all, we must always remember that a living center is living, is a being, only according to its position in a larger whole. It must help some larger whole. And if it is a being, it is helped by smaller wholes inside it, to the side of it, and far away from it.

따라서 존재와 같은 살아있는 중심은 현상이며, 공간 안에서 전기 같은 존재로서 주변의 협력, 즉 그것이 나타나는 더 큰 전체에 기여함으로써 생명을 얻는다. 이러한 진정으로 살아있는 특성이 바로 존재의 본질이다. So the being-like living center is a phenomenon, a nearly electric entity in space which gains its life by action at a distance, from the cooperation of the others all around it, from its contribution to the larger wholes with which it appears. This truly living quality is the being nature.

존재들은 통일성을 창조하고, 정의상 통일성의 일부이다. 각 존재, 즉 각 중심은 그들이 함께 형성하는 통일 안에서 서로의 존재로부터 생명을 얻는다. 그러나 이러한 존재들의 얽힌 삶은 본질적으로 동일한 I와 같은 성격에서 유래되며, 이는 I의 번식, I의 발전과 같다. 그것은 모두 I이다. 그것은 같은 것의 모든 표출, 발전, 강화를 포함한다. 천 개의 존재를 포함하는 구조는 만 개의 개별적인 존재가 아니다. 그것은 오직 하나의 존재이며, 단지 같은 이름, 하나의 소리, 하나의 목소리, 하나의 I, 하나의 통일성을 외치는 것이다. The beings create unity, and by definition are part of unity. Each being -- that is, each center -- gets its life from the existence of the other centers around it within the unity they form together. But the interwoven life of these beings, all essentially stemming from the same I-like character, is then like a proliferation, an elaboration of the I. It is all I. It is all manifestation, elaboration, intesification of the same. The structure which contains teh thousand beings is not ten thousand separate entities. It is one entity, only shouting the same name, one sound, one voice, one I, one unity.

10. The Fundamental Process

During the last thirty years I have often asked myself how people in traditional societies were able to make things which had such life and embodied living centers to such a high degree. It is unlikely, I think, that they used such detailed structural formulations as I have given in Books 1 to 3. However, it also seems unliekly that they had no formulations at all to guide them. One needs something clear to hang onto while one is working. It is therefore almost certain, in my mind, that the people of ancient cultures had at least some kind of intellectural formulation to guide them -- even if it was very different from what I have given.

What did a 14th-century mason say to himeself while carving the stone of a cathedral vault? What did a Turkish weaver say to herself while knotting a carpet? What did a Japanese temple carpenter think about while laying out his roof or planing the beams? These craftspeople made living structures -- I believe -- at a level of intensity and sophistication often far beyond our own capacities. How then, did they talk about it? What did they have in their minds while they were doing it?

I do not believe that traditional craftspeople -- in 14th-century Europe, for example -- usually carried such explicit theories in their minds. They worked; they acted; they knew what they were doing.

How did they know what they were doing? I believe that, in some form, they used the fundamental process in virtually everything they did. The fundamental process, discussed extensively in Book 2 and 3, is a process in which centers are made progressively more and more profound, more and more living, by an iterated, repeated, sequence of transformations.

How did they carry this process in their minds, and keep it before them?

I believe the following sentence expresses the kind of thing they might have carried, mentally, with them:

Whatever you make must be a being.

Stated at slightly greater length, it could be stated thus:

While you are making something you must always arrange things, or work things out, in such a way that all the elements you make are self-like beings, and the elements from which the elements are made are beings, and the spaces between these elements are beings, and the largest structures are beings, too. Thus your effort is directed toward the goal that everything, every portion of space, must be made a being.

11. The Difficulty of the Task

12. Innocence

13. The Vision of Matisse and Bonnard

14. In Our Own Era

15. A New Vision of Building: Making Living Structure in Our Brutal World

16. The Life of the Environment

5. The Practical Matter of Forging a Living Center

1. Intensifying Shape

2. Unity Achieved in a Great Blossom

3. Emergence of a "Being" From The Field of Centers

4. Beings in Arches, Spaces, and Columns: The Example of West Dean

5. Emergence of the Arches

6. Detailed Design of the Structural Columns

7. A Wall

8. Catching a Being in Color

9. The Haunting Melody

Mid-Book Appendix: Recapitulation of the Argument

1. Introduction

2. The Possibility of a Coherent Verifiable Theory

3. The Argument from Verifiable Details

4. The Argument From Coherence

Part Two

What I have presented in these four books is intended to become a part of a new science - a first sketch of a new kind of scientific theory.

Since the creation of a work of building must always be, at root, creation of living structure, I have built to the best of my ability a picture of living structure and of the processes that can generate living structure. The picture is sifficient, I belive, for working architects to carry in our minds, a vision of our task.

But this picture necessarily touches physics. The existence of living structure, as I have defined it, requires modifications in our physical picture of the world, not only in the picture which we have of architecture. And, in the most subtle phases of this work, we are forced - I believe - by the arguments presented in Book 4, to go still further. It is not enough merely to have a picture of living structure, but necessary, also, to recognize that there is something ineffable, a mystical core in things, that is deeply related to our own individual self, and that THIS -- not something else -- is the true both of matter and of architecture. That, too, must find expression.

6. The Blazing One

The Unity that Speaks of I

1. The Faintly Glowing Quality which Can be Seen in a Thing Which has Life

2. Psychological Explanation

3. Possible Existence of a Single Underlying Substance

4. The Blazing one

5. What, Then, Is a Center?

6. Though a Strange Model, It Provides a Viable Explanation

7. Which I-Hypothesis is True?

8. A Non-Material View of Matter

7. Color and Inner Light

1. Introduction: A Direct Glimpse of the I

2. Color as an Essential Feature of Reality

3. Inner Light

4. The Unfolding Which Produces Inner Light

5. The Eleven Color Properties

6. Hierarchy of Colors (Levels of Scale)

7. Colors Create Light Together (Positive Space, Alternative Repetition)

8. Contrast of Dark and Light (Contrast)

9. Mutual Embedding (Deep Interlock and Ambiguity)

10. Sequence of Linked Color Pairs (Gradients and the Void)

11. Boundaries and Hairlines (Boundaries)

12. Families of Color (Echoes)

13. Color Variation (Roughness)

14. Intensity and Clarity of Individual Colors (Strong Centers, Good Shape)

15. Subdues Brilliance (Inner Calm and Not-Separatedness)

16. Color Depends on Geometry (Strong Centers, Local Symmetries)

17. Color and the Field of Centers

18. Inner Light as a Glimpse of the I Which Lies Behind the Field of Centers

19. The Hint of a Transcendent Unity

20. Transcendent Wholeness as a Kind of Light

21. Conclusion

8. The Goal of Tears

1. Why Unity and Sadness are Connected

2. Sadness

3. Getting Sadness in the Flesh of the Building

4. Sadness of Color and Geometry

5. Unity and Sadness in a Group of Buildings

6. Unity and Sadness of Life in a Back yard

7. The Ground

8. Concluding Section

9. Making Wholeness Heals the Maker

1. Introduction

2. The Impact of Making Beauty on the Maker's Life

3. The Healing Process

4. Making Wholeness Heals the Maker

5. Life Made Creates Life in the Maker

6. The Source of the Healing Effect

7. Human Growth: The Movement of the Self Towards its Origin

8. Towards Full Knowledge of the Self Which Can Arise in Us

9. Drawing Sadness from Your Most Vulnerable Self

10. Do Not Ask for Whom the Bell Tolls

10. Pleasing Yourself

1. Introduction

2. Recaptulation of Books 1 to 4 as "Pleasing Yourself"

3. Veronica's blue Chair

4. The Heart-Stopping Quality

5. The Thought Police

6. Not Pleasing Yourself